economics

fiscal policy

Tax Forgiveness in Developing Countries: Between Fiscal Reform, Tax Ratio Pressure, and the Geopolitics of Global Tariffs

By Ang, SA

April 10, 2025

10 min read

This article explores tax forgiveness policies in developing countries, focusing on prominent case studies from Indonesia, Nigeria, and Argentina. It highlights how amnesty programs can generate short term revenue boosts and expand the tax base but often fail to improve long term tax compliance if not accompanied by structural reforms. The paper emphasizes that tax forgiveness whether through amnesties, pardons, or voluntary disclosure should be used as a one time tool within a broader reform agenda, including tax administration modernization, digital infrastructure, and improved governance. Ultimately, tax forgiveness is a policy instrument, not a sustainable fiscal strategy

In mid 2016, Indonesia faced a daunting tax challenge. With only 35 million registered taxpayers out of 165 million adults and as few as 12 million actually paying taxes in line with their true incomes the government launched one of the world's most ambitious tax amnesty programs. By the program's end in March 2017, an astonishing 965,000 Indonesians (including approximately 200,000 new taxpayers) had declared previously hidden assets worth IDR 4,865 trillion (US$366 billion) equivalent to nearly 40% of Indonesia's GDP. The government collected IDR 114 trillion (US$8.6 billion) in redemption payments, exceeding its initial target by 53%. Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati called it a "miracle" in public fiscal management.

A similar story played out in Nigeria in 2017 with the launch of the Voluntary Assets and Income Declaration Scheme (VAIDS). With Nigeria's tax to GDP ratio stuck around 6% one of the world's lowest policymakers hoped VAIDS would quickly broaden the tax base. The program registered an additional 814,000 taxpayers and collected ₦23 billion (US$47 million) from former evaders in just six months. Yet this fell far short of the ambitious ₦305 billion target (only ₦20 billion had been realized by early 2018), underscoring the difficulty of closing a massive tax gap with a short-lived amnesty.

These examples highlight a pervasive problem across the developing world: persistently low tax to GDP ratios. On average, low and middle-income economies collect only 15-20% of GDP in taxes, compared to over 30% in high income countries. Half of emerging markets and two-thirds of low income nations had tax ratios below 15% in 2020 a level often cited as a minimum threshold for sustainable development. Such meager revenues leave governments struggling to fund essential infrastructure, education, and health services, perpetuating a vicious cycle of weak state capacity.

The central question this analysis addresses is whether tax forgiveness represents a legitimate remedy for fiscal challenges or merely a risky shortcut that undermines long term tax compliance. This article argues that while tax forgiveness may offer temporary relief and create space for reform, such measures must be embedded within broader fiscal and structural transformation to avoid creating perverse incentives. Tax forgiveness whether in the form of amnesties, pardons, or voluntary disclosure programs serves as a policy tool, not a fiscal strategy. Without complementary reforms to address structural weaknesses in tax administration, governance frameworks, and economic fundamentals, tax forgiveness risks becoming a recurring and ineffective response to entrenched fiscal challenges.

Tax Forgiveness Deconstructed

Taxonomy of Forgiveness

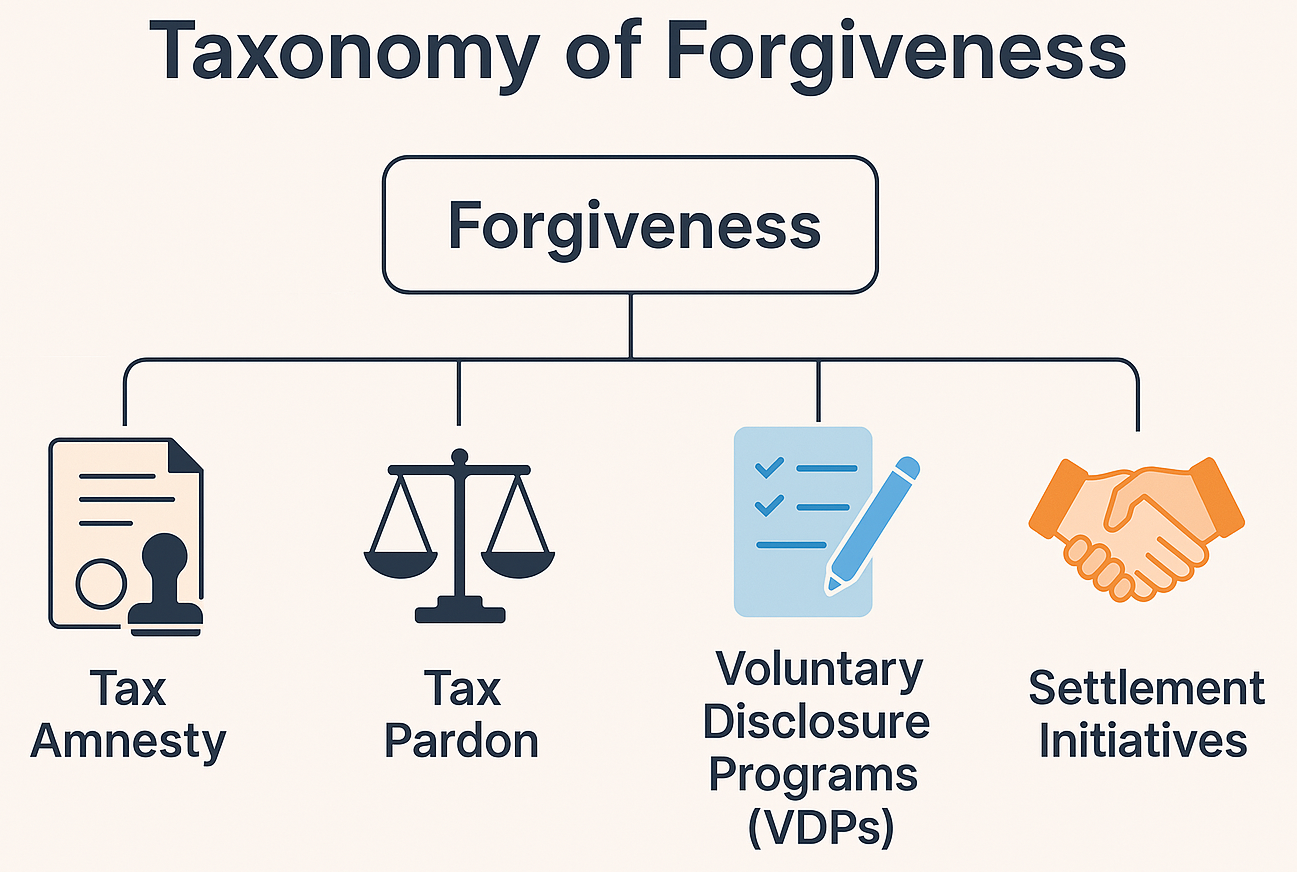

"Tax forgiveness" encompasses various policy instruments that differ in design, scope, and underlying motivations. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for evaluating their appropriateness and potential impact:

- Tax Amnesty: A time-limited opportunity for specified groups of taxpayers to pay a defined amount in exchange for forgiveness of tax liability (including interest and penalties) and legal immunity from prosecution. Indonesia's 2016-2017 program exemplifies this approach, offering varying redemption rates (2-10%) depending on timing and whether assets were repatriated. In most amnesties, participants must pay the full principal tax due (sometimes with a portion of interest) by the program deadline, after which they receive immunity for those past violations.

- Tax Pardon: A broader, often politically-motivated cancellation of tax liabilities affecting large segments of taxpayers. Nigeria's 2020 debt relief initiative for small businesses during COVID-19 represents a tax pardon responding to extraordinary economic circumstances. Pardons may include forgiveness of the tax principal itself, often granted by law or executive order to specific groups.

- Voluntary Disclosure Programs (VDPs): More limited in scope than amnesties, these programs encourage taxpayers to voluntarily correct past non-compliance in exchange for reduced penalties. India's 2016 Income Declaration Scheme allowed taxpayers to declare undisclosed income by paying tax, surcharge, and penalty totaling 45% of the undisclosed income. Unlike one-time amnesties, VDPs are typically ongoing policy tools that allow taxpayers to come forward at any time to declare previously undeclared earnings.

- Settlement Initiatives: These target specific sectors or tax issues, offering taxpayers standardized terms to resolve disputes with tax authorities. Argentina's 2016 "Tax Sincerization" program, which attracted $116.8 billion in declarations, exemplifies a hybrid approach combining settlement with broader amnesty features. Settlements often involve case-by-case negotiations between taxpayers and authorities to settle disputed or delinquent tax bills, typically by agreeing to pay a portion of the liability.

Historical and Global Context Tax forgiveness is not new countries both rich and poor have experimented with it for decades. In the mid 2010s, a wave of high-profile programs illustrated both the scale and diversity of modern amnesties:

In Argentina, newly elected President Mauricio Macri enacted a 2016 tax amnesty that became one of the world's largest ever. By its deadline, Argentines had declared $97.8 billion in previously hidden assets (mostly offshore), equivalent to about 21% of Argentina's GDP. Participants paid a tiered fee (roughly 5-15%) on these assets, yielding substantial one off revenue. The Argentine tax agency credited the amnesty (along with high inflation that year) for a 35% jump in tax revenue in 2016 compared to 2015.

India took aim at "black money" via the Income Declaration Scheme (IDS) 2016 a four month window to disclose untaxed income and assets. The result: 64,275 Indians admitted to ₹65,250 crore of undeclared assets (≈US$10 billion), on which they paid a 45% tax and penalty. It was touted as the largest-ever black money disclosure in India.

Indonesia's 2016 amnesty, noted earlier, offered rates as low as 2% for assets repatriated into Indonesia. While it fell short of some targets (only IDR 147 trillion of assets were repatriated versus IDR 1,000 trillion hoped), the public response surpassed expectations in declared asset value.

Varieties of Tax Forgiveness Programs

Tax forgiveness programs typically include one or more of the following components:

- Penalty Waivers: Elimination or reduction of penalties and interest charges on overdue tax liabilities. Egypt's 2022 initiative waived up to 65% of accumulated tax penalties to encourage settlement of core liabilities. Nigeria's VAIDS waived all interest and penalties for up to 6 years of back taxes if individuals and companies voluntarily declared and paid those liabilities.

- Principal Discounts: Partial forgiveness of the underlying tax liability itself. Pakistan's 2018 amnesty reduced effective tax rates to 2-5% of declared assets' value, compared to standard rates of up to 35%. Italy's repeated condono programs have occasionally allowed taxpayers to settle by paying only part of the assessed amount.

- Asset Repatriation Incentives: Preferential treatment for taxpayers who return offshore assets to the domestic economy. Indonesia's 2016 amnesty offered redemption rates as low as 2% for repatriated assets invested in designated economic sectors, versus 4-10% for simply declaring assets and keeping them abroad. Argentina similarly hoped its declarants would invest in Argentina's economy, and cited a new tax information agreement with the U.S. as additional motivation.

- Tax Holidays and Forward Looking Relief: Freedom from audit or investigation for past periods if taxpayers commit to full compliance moving forward. Mexico's 2019 "Conclusive Agreements" program guaranteed non-investigation of prior periods for taxpayers who settled current disputes and committed to future compliance. Some programs effectively grant a "holiday" from enforcement or certain taxes for a short period.

Policy Drivers

Understanding the true motivations behind tax forgiveness programs helps evaluate their potential efficacy:

- Fiscal Urgency: One straightforward reason is desperation for revenue. When budget deficits loom and conventional tax collection cannot be ramped up fast enough, an amnesty can deliver a quick infusion of cash. Argentina's 2016 amnesty came as the government was scrambling to rein in a high fiscal deficit. Pakistan and Turkey have periodically used amnesties to shore up revenues when other sources faltered.

- Widening the Tax Base: Indonesia explicitly designed its 2016 amnesty to capture data on previously unknown taxpayers, adding over 970,000 individuals to its tax registry. Nigeria's VAIDS was explicitly framed as a chance to increase taxpayer enumeration and gather valuable income data, not merely as a revenue drive.

- Political Gain and Signaling: A reformist administration might use an amnesty to symbolically break with the past, declaring "now is the time to come clean" before a tough enforcement regime begins. For example, every Italian tax amnesty tends to be labeled "the last, one-time chance" by politicians. Leaders may also seek popularity by appearing to offer taxpayers a deal.

- Data Collection: When very little is known about who owns what (common in high-evasion societies), an amnesty can serve as a mass audit by invitation. Indonesia's amnesty revealed trillions of rupiah held in Singaporean bank accounts. Many participants joined out of fear that new international data sharing (the OECD's Automatic Exchange of Information in 2018) would expose them anyway.

- Economic or Crisis Mitigation: In times of economic stress recession, conflict, commodity price collapse governments may deploy tax amnesty as part of a broader relief or recovery package. The logic might be to reduce the burden of tax liabilities to help businesses and individuals rebuild, or to encourage repatriation of capital during a currency crisis.

The explicit and implicit motivations behind tax forgiveness significantly influence program design and ultimate impact governments primarily seeking short-term revenue may create different incentives than those prioritizing structural reform of the tax system.

Measuring Impact

Evaluating tax forgiveness programs requires analysis of both immediate metrics and longer-term fiscal and compliance indicators. Evidence from varied implementations reveals a complex picture of costs and benefits.

Short-term vs. Long-term Effects

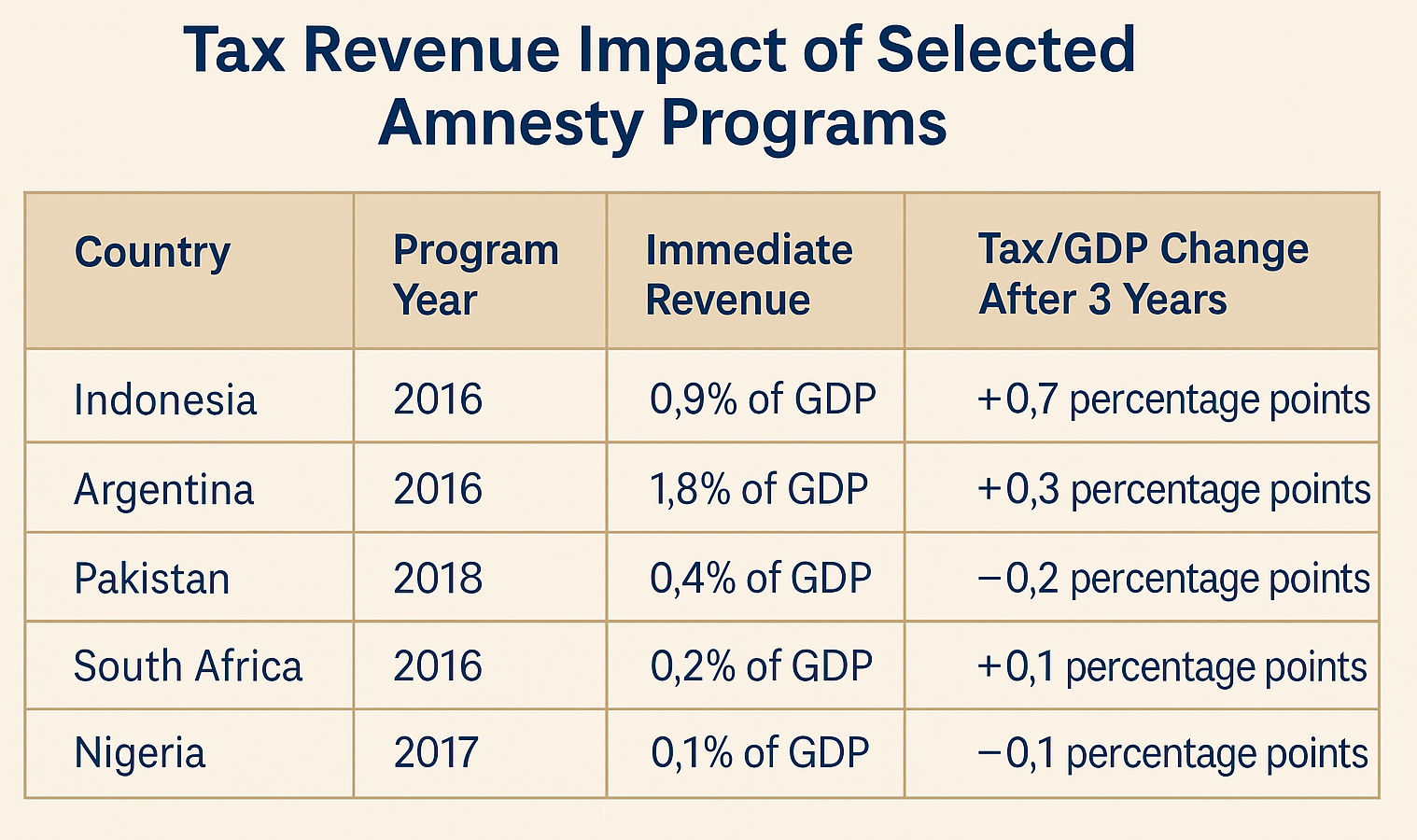

Short-term Outcomes: The immediate results of tax forgiveness programs often appear impressive. Indonesia's 2016 amnesty generated IDR 114 trillion (≈US$8.6 billion) in redemption payments (equivalent to nearly 0.9% of GDP) and declarations of IDR 4,865 trillion (US$366 billion) in previously undisclosed assets. Similarly, Argentina's 2016 program produced $9.5 billion in immediate revenue while bringing $116.8 billion of assets into the formal economy. The Argentine tax agency credited the amnesty (along with high inflation) for a 35% jump in tax revenue in 2016 compared to 2015.

Long-term Indicators: The picture becomes more ambiguous when examining sustained effects. A comprehensive study of 38 amnesty programs across developing countries between 2000-2020 found that while 76% met immediate revenue targets, only 23% showed statistically significant improvements in tax compliance three years later (IMF, 2022)

In some cases, the influx from an amnesty temporarily bumps up the tax toGDP ratio. For instance, Indonesia's tax ratio ticked up in 2016-2017 after the amnesty, before sliding again. The pattern of a one-time lift in revenue, often followed by reversion to pre-amnesty levels, is common across many programs.

Analyzing Key Performance Indicators

- Tax Ratio Increases: The most direct measure of success a sustained increase in tax to GDP ratios shows mixed results. Of the major amnesty programs implemented since 2015, only Indonesia demonstrated a sustained increase in tax ratio three years post implementation, rising from 10.8% to 11.5% of GDP. However, even this effect remains modest relative to the structural gap between developing and advanced economies.

- New Taxpayer Registration: Indonesia's program successfully added 970,000 new taxpayers to the formal system, increasing the tax registry by approximately 23%. However, follow-up compliance among these new registrants has been problematic by 2019, only 64% had submitted tax returns for subsequent years (Indonesian Tax Authority, 2020). Nigeria's VAIDS registered hundreds of thousands who had never filed before, which was one of the program's core objectives beyond revenue collection.

- Tax Buoyancy: A more sophisticated metric examines tax buoyancy how responsive tax revenue is to GDP growth. Evidence from Pakistan and Argentina suggests that post-amnesty buoyancy temporarily improved in the first year but regressed to previous levels by year three, indicating limited structural change in the relationship between economic activity and tax collection.

- Asset Recovery and Formalization: Perhaps the most substantial achievement of recent programs has been the formalization of previously undeclared assets. Indonesia's $366 billion in declarations (40% of GDP) and Argentina's $116.8 billion (21% of GDP) represent significant increases in the formal capital base, with potential long-term benefits for financial intermediation and capital market development. Additionally, if an amnesty targets asset declaration, the government might see capital inflows or increased liquidity in local markets. Indonesia's program is credited with boosting liquidity, strengthening the currency, and lowering interest rates in the short run as funds were brought onshore.

Moral Hazard and Behavioral Impacts

The central concern with tax forgiveness programs is behavioral response: how does forgiving past evasion affect taxpayers' future conduct and overall tax morale in society?

- Moral Hazard and Expectation Setting: Repeated amnesties create expectations of future forgiveness, undermining voluntary compliance. Pakistan's implementation of ten separate amnesty programs between 2000-2020 appears to have systematically reduced baseline compliance, with tax to GDP ratios declining from 13.3% to 11.4% over this period. Empirical evidence from Italy found that taxpayers who participated in an amnesty subsequently paid 5.3% less of their next tax bills compared to similar taxpayers who did not participate. In other words, those who got used to amnesty relief were slightly more likely to default later, presumably hoping for yet another break.

- Compliance Erosion Among Previously Compliant Taxpayers: When honest taxpayers witness forgiveness granted to evaders, their own compliance may deteriorate. A survey of 1,200 Argentine taxpayers conducted in 2018 found that 47% of regular tax compliers reported "decreased motivation to pay taxes on time" following the 2016 amnesty (Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2018). Over time, such behavior can cancel out the initial revenue gains. Some studies have found that a portion of amnesty participants would have paid in full without any forgiveness meaning the government essentially gave up revenue it could have collected. The IMF's review of amnesties concluded that "the perceived benefits of tax amnesty programs are at best overstated" and often do not exceed their true costs.

- Inequality Perception: Amnesties often favor wealthy individuals with offshore assets, potentially exacerbating perceptions of systemic inequality. In South Africa, public controversy erupted when data revealed that 75% of the assets declared in the 2016 amnesty belonged to the wealthiest 1% of participants (South African Revenue Service, 2018). This sense of inequity was a common critique in Indonesia the amnesty was seen as unfairly favoring wealthy tax evaders (no questions asked about sources of funds, immunity from other laws like money laundering). Such perceptions can discourage compliant behavior among previously law abiding citizens.

- Fiscal Dependency: Perhaps most concerning is the development of institutional dependency on periodic amnesties as revenue sources. This "amnesty cycle" can be observed in countries like Pakistan, where amnesty revenue has constituted an average of 2.7% of total tax collections over the last decade effectively becoming an institutionalized component of the fiscal architecture rather than an exceptional measure.

When Can Amnesties Work?

Research and experience suggest a few conditions where the benefits might outweigh the costs:

- The amnesty is truly one-off and accompanied by structural changes (new laws, better enforcement tools, international agreements) that make future evasion harder. Taxpayers then view it not as a recurring pardon, but as a transition into a stricter era.

- The program is designed to maximize immediate gains without giving away too much. This means keeping discounts modest, ensuring high participation through good publicity, and not undercutting normal compliance too severely.

- It targets areas of evasion that would be very hard to detect otherwise, such as offshore assets before global transparency initiatives.

- It occurs in a context of broader reform where it complements other efforts, using the amnesty to clean the slate and enable a new system to begin with more taxpayers on board.

Without such conditions, amnesties often provide a short-term revenue boost followed by a crash in compliance or at best a return to the status quo. As one U.S. Treasury analysis put it, "this net revenue loss [from an amnesty] occurs primarily because... overall taxpayer compliance [is reduced]" in the long run.

Tax System Structure in Developing Countries

The efficacy of tax forgiveness programs cannot be separated from the broader structural features of tax systems in developing economies. These systems typically differ from those in advanced economies in both composition and administrative capacity.

Common Tax Types and Their Effectiveness

Value Added Tax (VAT): Most developing countries rely heavily on consumption taxes, with VAT typically generating 25-40% of total tax revenue. While VAT offers advantages in administration and compliance, its inherently regressive nature raises equity concerns. Additionally, exemptions and reduced rates for essential goods create complexity and opportunities for evasion. Indonesia's VAT, which accounts for 31% of tax revenue, suffers from significant compliance gaps estimated at 40% of potential collections.

Personal Income Tax (PIT): Income taxation in developing countries faces fundamental challenges from high informality and limited third party reporting. With formal employment often comprising less than half the workforce, traditional withholding mechanisms capture only a small portion of the potential base. In Nigeria, PIT contributes just 13% of tax revenue despite its population of over 200 million, reflecting administrative limitations and widespread evasion.

Corporate Income Tax (CIT): While CIT rates in developing countries average 25-30% (higher than the OECD average of 23.5%), effective tax rates often fall to single digits due to generous incentives, weak enforcement, and profit shifting. International efforts like the OECD's Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative have yet to fully address the estimated $200 billion in annual revenue losses to developing countries from corporate tax avoidance.

Wealth and Property Taxes: Despite their potential for revenue and progressivity, wealth and property taxes remain underutilized in developing countries, typically generating less than 1% of GDP compared to 2-3% in advanced economies. Administrative challenges in valuation, registries, and enforcement create significant obstacles to effective implementation.

Custom Duties and Trade Taxes: Many low income countries continue to rely heavily on import duties and export taxes, accounting for 15-30% of tax revenue in countries like Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Nepal. While administratively straightforward, these taxes create economic distortions and vulnerability to trade shocks.

Sin and Environmental Taxes: Taxes on tobacco, alcohol, carbon emissions, and other externality generating activities represent a growing but still minor component of developing country tax systems. These taxes offer the dual benefit of revenue generation and social policy alignment, though implementation often faces significant political resistance.

Structural Constraints and Administrative Challenges

Several underlying factors limit tax system effectiveness in developing economies:

- Informality: With informal sectors averaging 30-40% of GDP in developing countries, significant economic activity remains beyond the reach of conventional tax instruments. Tax forgiveness programs rarely address this fundamental constraint, as those operating entirely outside the formal economy have limited incentive to participate.

- Administrative Capacity: Tax administrations in developing countries typically employ significantly fewer staff relative to population Argentina's tax authority has 1,957 staff per million citizens compared to 2,785 in the United Kingdom. This capacity gap undermines both enforcement and taxpayer services.

- Digital Infrastructure Limitations: While digitalization offers transformative potential for tax administration, many developing countries struggle with basic prerequisites like reliable electricity, internet connectivity, and digital literacy. Only 32% of African tax administrations have fully functional e-filing systems, compared to 96% in OECD countries (ATAF, 2023).

- Shadow Economy and Illicit Financial Flows: The shadow economy extends beyond conventional informality to include criminal activities and deliberately concealed transactions. Global Financial Integrity estimates that illicit financial flows from developing countries exceed $1 trillion annually, dwarfing official development assistance and foreign direct investment combined.

- Political Economy Constraints: Perhaps most fundamentally, political resistance to effective taxation remains entrenched in many developing countries. Elites who benefit from weak enforcement often control policy levers, creating a circular problem where those with the capacity to pay taxes also have the power to prevent effective taxation.

These structural constraints help explain why tax forgiveness programs often fail to generate sustained improvements. Without addressing fundamental weaknesses in the tax system architecture, amnesties and similar measures may temporarily boost revenue without changing the underlying dynamics that produce persistent compliance gaps. —"declare now before automatic exchange makes evasion impossible"

Political Cover for Reform: External economic pressure provides political cover for implementing otherwise unpopular tax measures, including both forgiveness programs and subsequent reforms.

The relationship between global economic turbulence and domestic tax forgiveness is evident in timing: Indonesia's 2016 amnesty followed a 12% depreciation of the rupiah; Argentina's program coincided with its recovery from a recession; South Africa's voluntary disclosure initiative came amid its first economic contraction in seven years. These patterns suggest that external pressure often serves as both motivation and justification for tax forgiveness measures.

Strategic Policy Pathways

Given the complex relationship between tax forgiveness, structural constraints, and external pressures, policymakers face difficult strategic choices. This section presents scenario simulations and trade-off analyses to inform these decisions.

Scenario Simulation

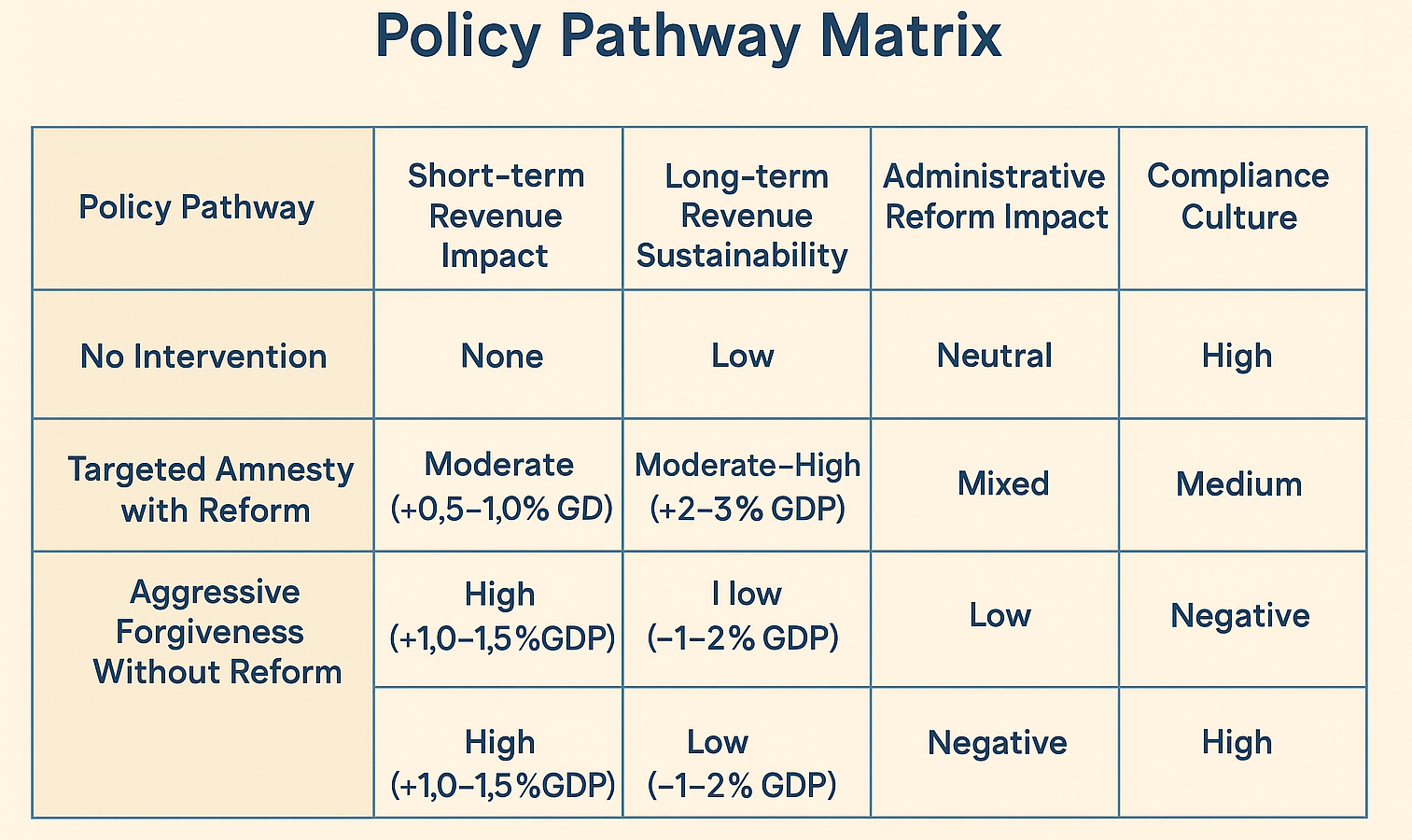

Three prototypical approaches to tax forgiveness yield distinctly different outcomes:

Scenario 1: No Intervention (Status Quo)

- Tax-to-GDP ratio remains stagnant at 14-15% (typical developing country average

- Compliance gap persists at 35-40% of potential revenue

- Informal economy maintains 30-35% share of GDP

- Fiscal deficit averages 4-5% of GDP annually

- Public investment in infrastructure and social services remains constrained

- Long-term economic growth averages 3-4% annually

Scenario 2: Targeted Amnesty with Administrative Reform

- Initial revenue boost of 0.5-1.0% of GDP in amnesty year

- Tax registry expands by 15-25% through new declarations

- Investment in digital tax systems and staff capacity using amnesty proceeds

- Gradual improvement in tax-to-GDP ratio to 16-18% over five years

- Reduction in compliance gap to 25-30% of potential revenue

- Increased detection capability through improved data analytics

- Modest formalization of previously undeclared economic activity

- Fiscal deficit reduction to 3-4% of GDP

- Moderate improvement in public service delivery

- Long-term economic growth potential increases to 4-5% annually

Scenario 3: Aggressive Forgiveness Without Reform

- Larger immediate revenue boost of 1.0-1.5% of GDP

- Short-term political popularity gains

- Temporary fiscal space creation

- Expectation of future amnesty established

- Deterioration in voluntary compliance among previously compliant taxpayers

- Return to pre-amnesty tax-to-GDP levels within 2-3 years

- Deepening perception of tax system inequality

- Development of "amnesty addiction" in fiscal management

- Long-term erosion of tax morale and compliance culture

- Persistent structural weaknesses in tax administration

- Continued fiscal fragility and vulnerability to external shocks

Trade-off Analysis

These scenarios highlight several critical trade-offs that policymakers must navigate:

Short-term Revenue vs. Long-term Compliance: The most immediate trade-off involves sacrificing potential long-term revenue stability for immediate gains. Indonesia partially addressed this dilemma by earmarking amnesty proceeds for tax administration modernization, creating a virtuous cycle where short-term revenue funded capacity improvements for long-term collection.

Equity vs Simplicity: Designing forgiveness programs that balance simplicity (to encourage participation) with equity (to avoid rewarding the worst offenders) presents significant challenges. South Africa's program attempted to address this by implementing a tiered penalty structure based on the severity and duration of non-compliance.

Domestic Autonomy vs. International Coordination: While nationally designed forgiveness programs offer policy flexibility, international coordination prevents "amnesty shopping" across jurisdictions. The Joint International Tax Shelter Information and Collaboration (JITSIC) network represents a promising model for such coordination, though participation from developing countries remains limited.

Administrative Focus vs. Structural Reform: Perhaps most fundamentally, governments must decide whether to address symptoms (through forgiveness and administrative improvements) or underlying causes (through structural economic transformation). The evidence suggests that successful programs combine both approaches using forgiveness as an entry point for deeper reforms rather than a substitute.

Conclusion

Tax forgiveness programs represent a dual-edged sword in developing country fiscal management. At their best, they serve as strategic entry points for deeper reforms, generating immediate revenue while creating space for administrative modernization and compliance culture development. At their worst, they function as addictive fiscal palliatives, providing short-term relief while undermining the very tax morale and compliance norms upon which sustainable taxation depends. The evidence surveyed in this analysis suggests several crucial insights for policymakers:

First, context matters profoundly. The same forgiveness program design that succeeded in Indonesia failed in Pakistan, largely due to differences in implementation credibility, accompanying reforms, and macroeconomic circumstances. Policy transfer must consider these contextual factors rather than simply importing design elements from "successful" cases.

Second, forgiveness must be exceptional rather than routine. The contrast between Indonesia's comprehensive "once-in-a-generation" approach and Pakistan's regular use of amnesties as fiscal tools illustrates the importance of maintaining the exceptional character of forgiveness measures. When amnesty becomes expected, it transforms from a transitional mechanism into a dysfunctional component of the regular tax system.

Third, administrative reform must accompany forgiveness. The data consistently shows that forgiveness programs delivered in isolation produce minimal sustained revenue improvements. Programs that reinvest proceeds into administration, leverage gathered data for compliance management, and implement broader structural reforms show markedly better long term outcomes.

Fourth, external factors increasingly shape domestic tax policy space. As global trade tensions, international tax cooperation, and macroeconomic volatility intensify, developing countries must design tax systems resilient to external shocks rather than relying on forgiveness programs as emergency responses to crisis.

Ultimately, tax forgiveness programs reflect a fundamental tension in developing country governance the need to generate immediate revenue while building institutions capable of sustainable domestic resource mobilization. Resolving this tension requires recognizing that forgiveness represents a tool, not a strategy. The strategic challenge lies in embedding forgiveness within comprehensive reform agendas that address the structural constraints on effective taxation in developing economies.

As Indonesia's Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati observed following her country's amnesty: "The program's success will not be measured by the declarations made or the revenue collected, but by whether it marks the beginning of a new compliance culture or merely a temporary deviation from business as usual." Three years later, with Indonesia's tax to GDP ratio showing modest but sustained improvement, her observation offers a fitting metric for evaluating all such programs not as ends in themselves, but as potential catalysts for the deeper transformation that developing country tax systems urgently require

References

- African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF). (2023). African Tax Outlook 2023. Pretoria: ATAF.

- Indonesian Tax Authority. (2020). Tax Amnesty Follow-Up Compliance Report. Jakarta: Ministry of Finance.

- International Monetary Fund. (2022). Tax Amnesties: Evidence from 38 Developing Countries. IMF Working Paper WP/22/56.

- South African Revenue Service. (2018). Special Voluntary Disclosure Programme: Final Report. Pretoria: SARS.

- Universidad de Buenos Aires. (2018). Tax Compliance Survey: Post-Amnesty Attitudes. Buenos Aires: UBA Faculty of Economics.