Real Rate Matters: Why Inflation and Nominal Rates Often Mislead Investors

This article highlights why focusing on nominal interest rates alone can lead to major investment mistakes and policy errors. The real interest rate calculated by subtracting inflation from nominal rates offers a more accurate measure of monetary conditions and true investment returns. Drawing from historical crises in the US, Turkey, and Indonesia, the research shows how negative real rates can fuel inflation, trigger capital flight, and destabilize currencies, even when nominal rates appear high. The Fisher Equation serves as the key framework for understanding this relationship, emphasizing the role of inflation expectations and central bank credibility. As of 2025, global real rate conditions remain highly uneven across regions, shaping capital flows, currency stability, and asset valuations. The article outlines three potential future scenarios through 2030 from successful disinflation to persistent inflation shocks and policy mistakes. Understanding real rates is critical for informed portfolio decisions across bonds, equities, currencies, and commodities. This piece provides investors and policymakers with the insights needed to navigate monetary uncertainty and avoid the trap of headline nominal rates.

Rising nominal interest rates don't always indicate tight monetary conditions, and investors who misunderstand this fundamental concept often make costly allocation errors. Real interest rates nominal rates minus inflation provide the true measure of monetary conditions and actual investment returns. This research examines why focusing solely on nominal rates leads to investment misconceptions, demonstrates how real rates reveal hidden economic dynamics, and provides actionable strategies for investors navigating today's complex monetary landscape.

The Nominal Trap

In financial markets and economic policy discussions, nominal interest rates often dominate headlines and market commentary. However, focusing solely on these headline rates without accounting for inflation can lead to significant investment errors and policy misjudgments. This phenomenon what we term "the nominal trap" has repeatedly confused investors and policymakers throughout economic history.

Rising nominal rates do not necessarily indicate tight monetary conditions. The 1970s stagflation era vividly demonstrated this paradox: despite Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker pushing nominal rates to nearly 20%, persistently high inflation meant real rates remained negative for extended periods, ultimately requiring even more aggressive monetary tightening. Similarly, emerging market debt crises including Indonesia in 1997 and Argentina's recurring financial troubles often stemmed from a fundamental misreading of monetary conditions based on nominal rates alone.

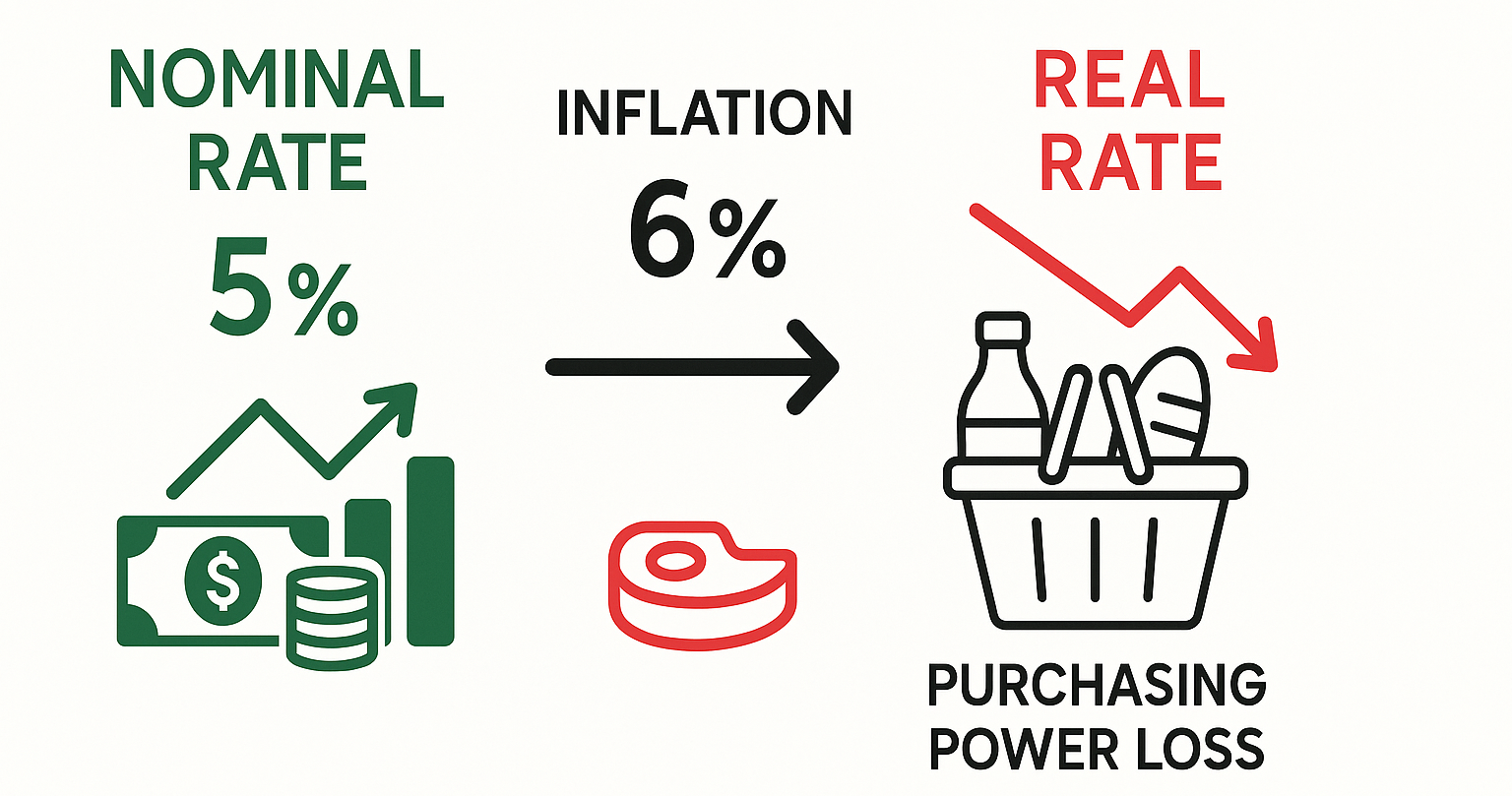

The basic concept is straightforward but frequently overlooked: Real Interest Rate = Nominal Rate – Inflation Rate. This calculation reveals the true cost of capital and the genuine incentive to save or invest. When real rates are negative, money loses purchasing power over time despite positive nominal returns, discouraging saving and encouraging borrowing and spending potentially fueling further inflation.

Nominal is what you see. Real is what you get.

Understanding the Real Rate

The relationship between nominal rates, real rates, and inflation was formally articulated by economist Irving Fisher in what became known as the Fisher Equation. In its simplest form, this equation states:

i = r + π^e

Where:

- i = nominal interest rate

- r = real interest rate

- π^e = expected inflation rate

This foundational concept forms the basis for understanding monetary policy, investment returns, and economic forecasting across diverse market environments.

This formulation highlights a crucial distinction between two types of real rates:

-

Ex-ante real rates are based on expected inflation and represent forward-looking decision-making variables for economic agents. These anticipated rates guide investment decisions and policy formulation.

-

Ex-post real rates are calculated using realized inflation and measure actual economic outcomes retrospectively. These rates reveal the true returns or costs after inflation has manifested.

The discrepancy between ex-ante and ex-post real rates often stems from inaccurate inflation expectations, which are heavily influenced by central bank credibility. When monetary authorities have strong anti-inflation credibility, inflation expectations remain anchored, allowing nominal rates to more directly influence real rates. Conversely, when central bank credibility weakens, inflation expectations can become unmoored, requiring higher nominal rates to achieve the same real rate effect.

Real rates function as critical signals of:

- Policy stance: Positive real rates indicate restrictive monetary policy that constrains economic activity, while negative real rates suggest accommodative policy that stimulates spending.

- Investment attractiveness: Positive real yields provide genuine returns that preserve or enhance purchasing power, making such investments attractive for savers.

- Currency stability prospects: Currencies backed by positive real rates typically demonstrate greater stability.

- Overall financial conditions across an economy: The real rate environment shapes borrowing, lending, and investment behaviors.

3. Historical Case Studies: When Nominal Lies

Historical episodes provide compelling evidence of how focusing on nominal rates alone can lead to serious economic misjudgments:

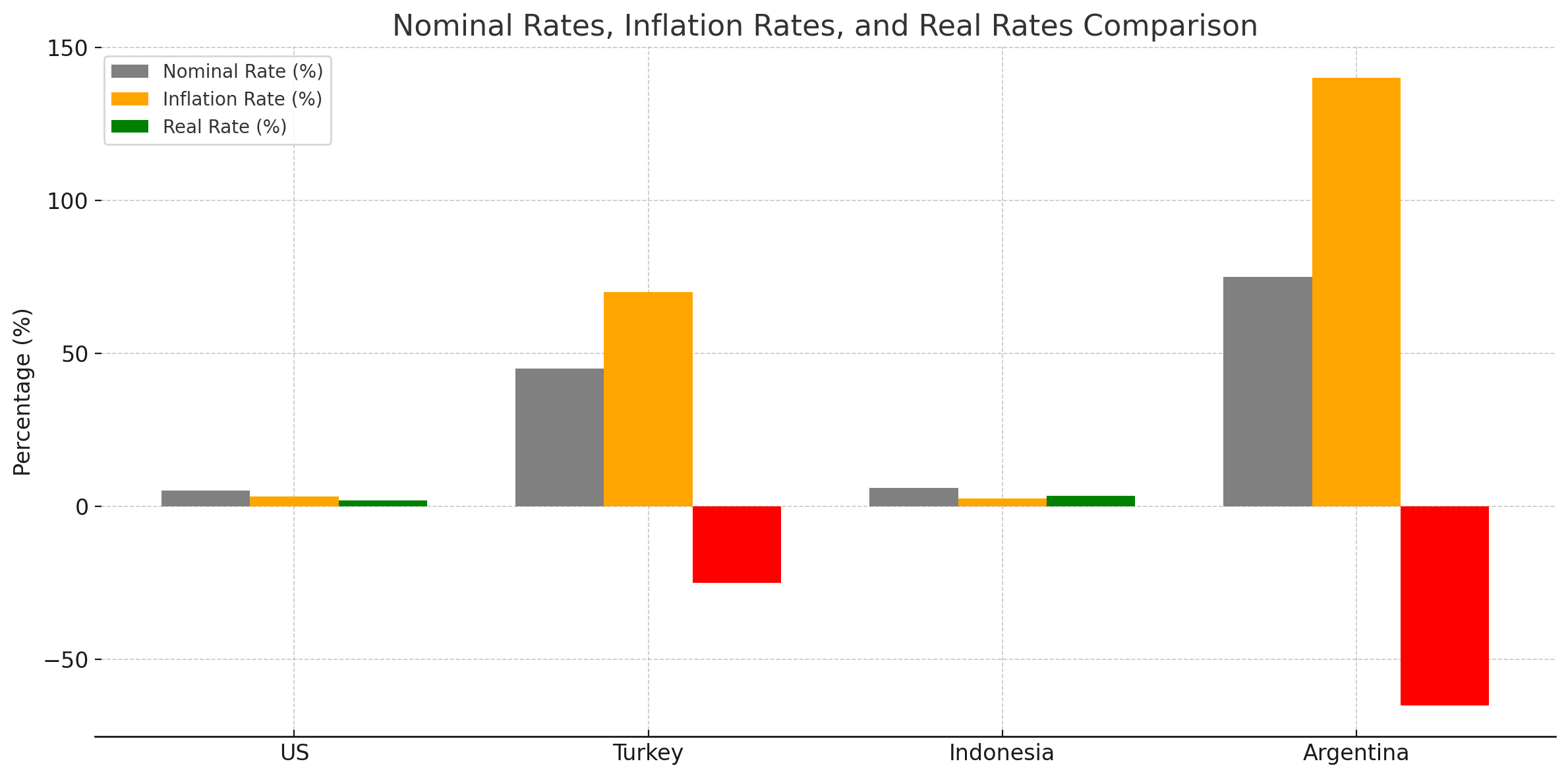

United States (1970s): During this tumultuous period, nominal interest rates reached historically high levels, yet inflation surged even higher. Despite the Federal Reserve raising the federal funds rate to unprecedented levels (peaking at 19.1% in June 1981), real rates remained negative for much of the decade due to inflation exceeding 10%. In the late 1970s, while nominal rates exceeded 10%, inflation peaked above 14%, resulting in negative real rates. This negative real rate environment fueled rather than restrained inflation, requiring Paul Volcker's extreme monetary tightening to finally break the inflationary spiral. Only when the prime lending rate was pushed above 21%, finally creating firmly positive real rates, did inflation begin to subside.

Turkey (2018-2023): Turkey's central bank maintained policy rates between 14-24% during much of this period nominally high by global standards. However, with inflation surging well above 50% (reaching 85.5% in October 2022), real rates remained deeply negative, ranging from -22% to an extreme -71.5%. This persistent negative real rate environment triggered severe capital flight and contributed to the dramatic devaluation of the Turkish lira, creating economic instability despite superficially "high" interest rates.

Indonesia (1997 Asian Financial Crisis): Prior to the crisis, Indonesia attracted substantial capital inflows chasing high nominal yields of 10-15%. Foreign investors largely ignored underlying inflation and currency risks. When the crisis hit, the Indonesian rupiah collapsed by over 80% against the US dollar, with rapid depreciation starting in August 1997 and accelerating dramatically in January 1998. Real GDP declined by 12-14% in 1998, while food prices exploded, increasing three-fold between January 1998 and March 1999. This crisis exposed the fallacy of focusing solely on nominal returns, as seemingly attractive nominal yields had masked deeply negative real returns.

Table: Nominal vs. Real Rates in Key Historical Episodes

| Country/Period | Nominal Policy Rate (Peak) | Inflation Rate (Peak) | Real Rate | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US (1979-1981) | 19.1% | 14.8% | +4.3% | Inflation defeated but at cost of severe recession |

| Turkey (2022) | 14.0% | 85.5% | -71.5% | Currency collapse, economic crisis |

| Indonesia (1997-1998) | 81.0% | Food prices up 300% | Deeply negative | Currency crisis, GDP fell 12-14% |

| Argentina (2022) | 75.0% | 94.8% | -19.8% | Continued economic instability |

Global Snapshot: Current Real Rates Landscape (2025 Update)

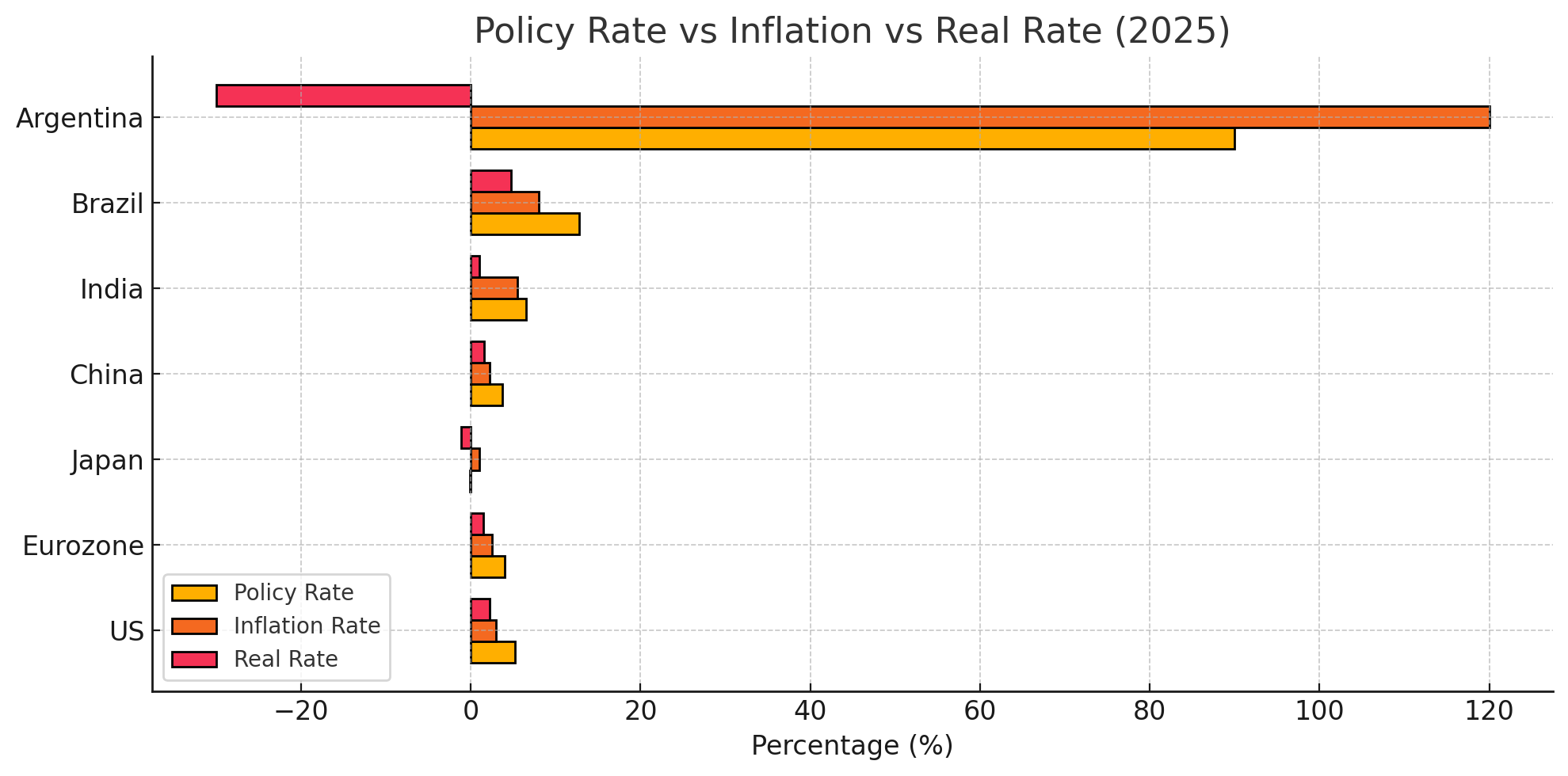

As of early 2025, the global real rate environment presents a complex and varied picture, with significant implications for capital flows and investment strategies:

Advanced Economies:

United States: With economic activity remaining robust and projected real GDP growth of 2.2% for 2025, the Federal Reserve maintains a careful balance. The Fed's policy rate stands at 3.75%, with core PCE inflation at 2.3%, resulting in a positive real rate of approximately +1.45%. This relatively tight policy stance reflects the Fed's commitment to maintaining price stability following the inflationary pressures of the early 2020s and has supported the dollar while attracting global capital flows.

Eurozone: The ECB maintains a deposit facility rate of 2.5% against headline inflation of 2.1%, yielding a modest positive real rate of +0.4%. With real GDP growth projected at 1.3% in 2025 exceeding 1% for the first time in three years the European Central Bank faces less inflationary pressure than the US. This represents a significant shift from the negative real rate environment that persisted for much of the previous decade.

Japan: After ending its negative interest rate policy in 2023, the Bank of Japan now holds its policy rate at 0.75% with inflation at 1.8%, resulting in a slightly negative real rate of -1.05%. With real GDP growth projecting toward 1.1% in 2025, Japan continues its long struggle with low inflation and growth, maintaining a relatively accommodative stance despite modest nominal rate increases.

Emerging Economies:

The picture across emerging markets is more varied, with this group collectively expected to grow at 4.1% in 2025.

China: Despite fiscal and monetary policy support, China faces structural property sector and demographic challenges, with real GDP growth expected to slow to 4.5% in 2025. Real rates remain relatively low as authorities balance growth concerns against financial stability.

India: Standing out as a bright spot with real GDP growth expected at 6.4% in 2025, driven by public investment and strong domestic demand. Higher real rates help control inflation while still allowing robust growth. India maintains positive real rates (+1.2%).

Southeast Asia: A mixed picture, with countries like the Philippines continuing to operate with marginally negative real rates (-0.5%).

Latin America: Brazil leads with strongly positive real rates (+3.5%), while Argentina continues to struggle with deeply negative real rates despite nominally high policy rates.

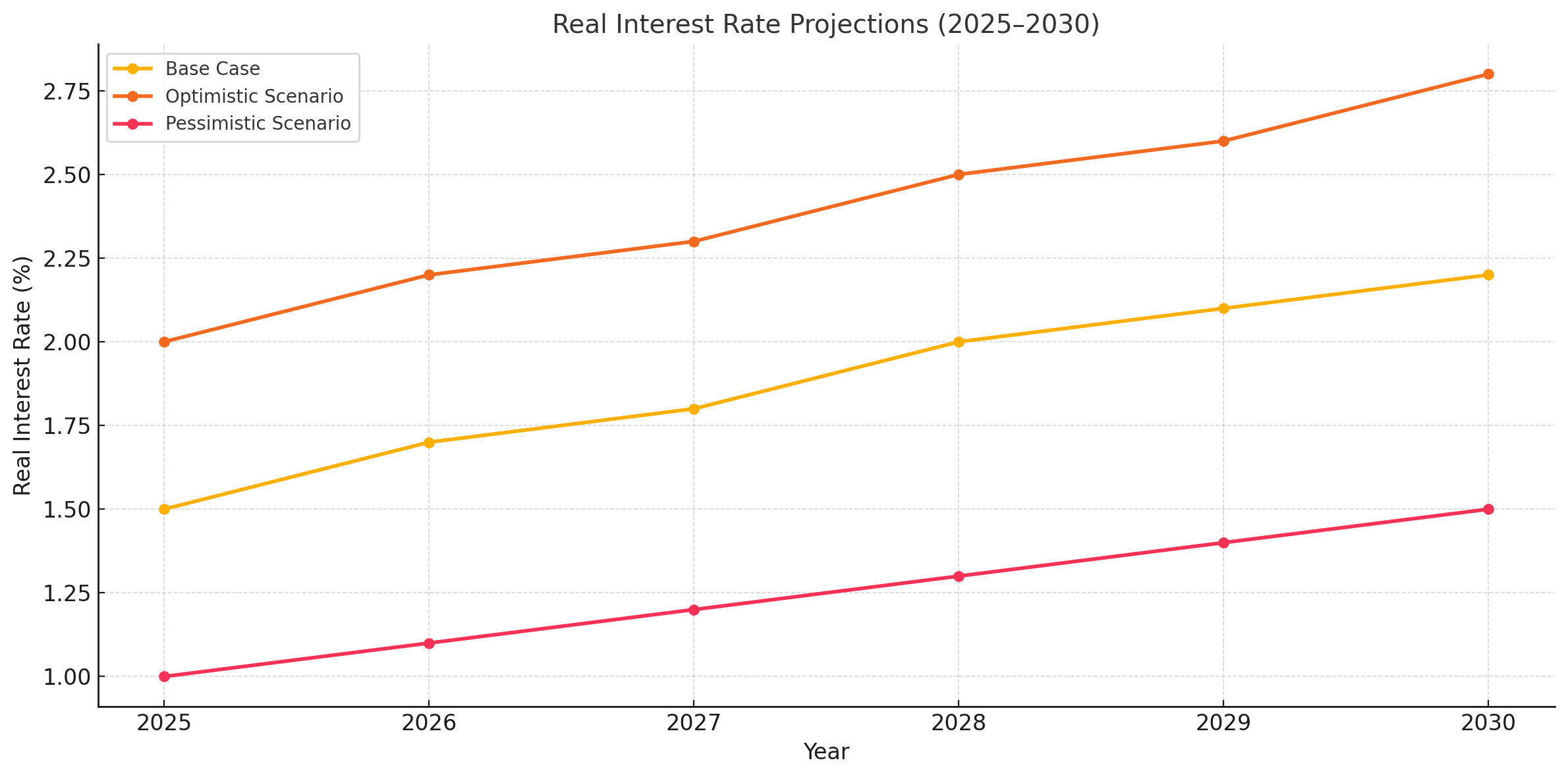

Forecasting Real Rate Scenarios: 2025-2030 Outlook

Looking ahead, three distinct scenarios could shape the trajectory of real interest rates globally over the next five years:

Scenario 1: Disinflation Success (Soft Landing)

- Global inflation steadily declines from 4.5% in 2024 to the pre-pandemic level of 3.1% by 2027

- Inflation gradually normalizes to target ranges (1.8-2.2%) across developed markets

- Central banks begin measured policy rate reductions

- Real rates remain moderately positive (+0.5% to +1.5%)

- Economic growth stabilizes at sustainable levels, with advanced economies averaging 1.8-2% growth and emerging markets around 4-4.5%

- Implication: Balanced investment environment favoring quality fixed income and selective equity exposure

Scenario 2: Persistent Inflation Shock

- Structural factors like deglobalization, climate change adaptation costs, and demographic constraints keep inflation elevated above 4% through 2028

- Inflation resurges above 4% in developed markets due to supply constraints, geopolitical tensions, or wage-price spirals

- Central banks forced to maintain or raise nominal rates

- Real rates struggle to turn meaningfully positive as central banks balance inflation concerns against growth and financial stability risks

- Growth becomes erratic with heightened volatility

- Implication: Challenging environment favoring inflation-protected securities, commodities, and select real assets

Scenario 3: Policy Mistake / Premature Easing

- Central banks reduce rates too quickly in late 2025 and 2026, before inflation is fully contained

- Inflation rebounds above targets (3-5% range)

- Real rates turn negative again

- Asset bubbles form in various markets

- This premature easing triggers a reacceleration of inflation by 2027, forcing central banks to reverse course and hike rates again

- Creates a "stop-go" cycle that undermines credibility

- Implication: Initial asset price boom followed by instability; favors tactical positioning and active management

Implications across scenarios for:

- FX stability: Positive real rates typically support currency strength; in Scenario 3, FX markets would experience whipsaw movements with significant volatility

- Capital flows: Emerging markets with positive real rates likely to attract investment; in Scenario 2, flows become erratic favoring commodity exporters; in Scenario 3, capital flows surge then suddenly reverse

- Bond yields: Term premium likely to increase in scenarios 2 and 3; in Scenario 3, yields decline initially then spike higher, causing significant mark-to-market losses

- Equity risk premiums: Higher in scenarios of negative real rates or heightened uncertainty; in Scenario 3, equity markets rally on initial easing then correct sharply when inflation rebounds

The Real Rate Puzzle in Emerging Markets

Emerging economies consistently face a structural challenge in maintaining positive real interest rates. While these countries often maintain higher nominal interest rates than developed markets, their real rates frequently remain lower or even negative, creating persistent vulnerabilities.

Several factors contribute to this real rate puzzle:

Structural Vulnerabilities:

- Weak inflation anchoring: Without the decades-long credibility built by major central banks, emerging market inflation expectations can become unanchored more easily during economic shocks, requiring larger nominal rate increases to achieve the same real rate effect.

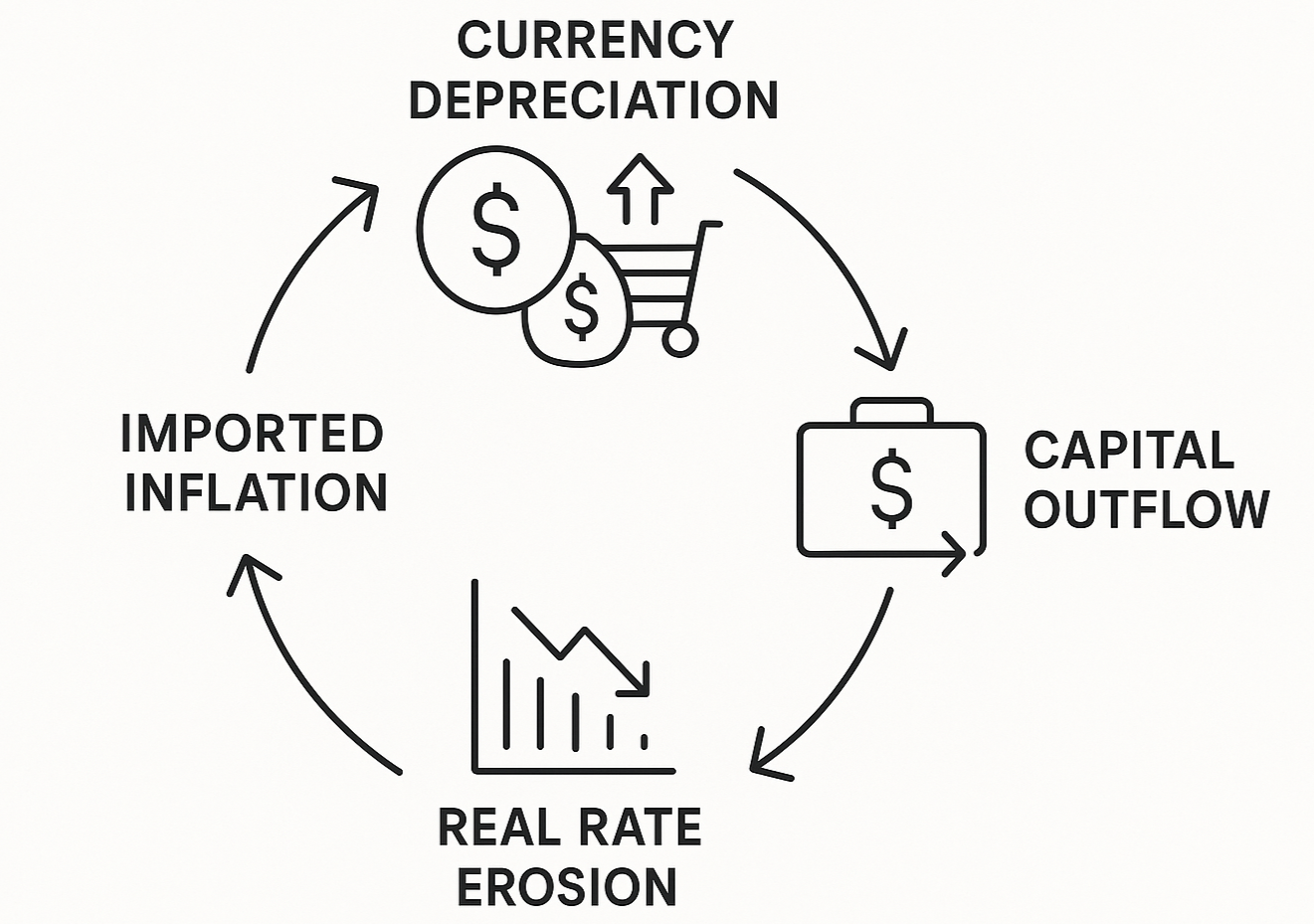

- FX pass-through effects: Currency depreciation in emerging markets often leads to significant inflation through imported goods, creating a self-reinforcing cycle where falling currencies lead to higher inflation, more negative real rates, further capital outflows, and additional currency weakness.

- Political pressure on central banks: Many emerging market central banks face greater political interference than their advanced economy counterparts, potentially limiting their ability to raise rates sufficiently to achieve positive real rates during inflationary periods.

- Capital flow volatility: Creating boom-bust cycles that complicate monetary policy implementation.

Case Study: Indonesia During the 1997-1998 Asian Financial Crisis, despite rapidly rising interest rates, Indonesia experienced food price inflation of approximately 300%, creating deeply negative real rates that contributed to capital flight and currency collapse. The rupiah-US dollar exchange rate depreciated massively starting in January 1998, with some recovery after September 1998, but began slowly depreciating again at the end of 1999 and through 2000.

More recently, Bank Indonesia's policy rate (BI Rate) has averaged 4.8% over the past five years, while core inflation has averaged 3.2%, resulting in a positive real rate of approximately 1.6%. This positive real rate stance has helped maintain relative currency stability compared to regional peers with negative real rates.

Data Insight Box: "Indonesia's real policy rate has averaged +1.6% over the past 5 years providing sufficient premium to attract foreign capital while maintaining domestic economic growth. Countries with persistently negative real rates in the region have experienced significantly greater currency volatility. However, during periods of global market stress, Indonesia remains vulnerable to capital flight pressures."

Investment Implications: Why Real Rates Matter for Portfolio Decisions

Understanding real rates is essential for investment decisions across all major asset classes:

Fixed Income:

- Negative real yields lead to erosion of purchasing power for bondholders. For instance, a bond yielding 3% in an environment with 5% inflation delivers a real return of -2%, meaning the investor loses purchasing power despite receiving positive nominal income.

- Positive real yields offer genuine income-generating safe assets that preserve or enhance purchasing power.

- Current environment (2025): Selective opportunities in markets with positive real yields, particularly in high-quality sovereign and investment-grade corporate bonds.

Equities:

- Real rates function as the foundational discount rate for equity valuations through the discount rate effect. Higher real rates increase the discount rate applied to future earnings, compressing valuation multiples.

- High real rates typically compress price-to-earnings ratios through higher cost of capital, particularly for growth stocks with earnings weighted toward the distant future.

- The 1970s stagflation era demonstrated how persistently negative real rates initially fueled an inflationary environment that eventually led to equity market underperformance.

- Sectors with long-duration cash flows (technology, growth) most sensitive to real rate shifts.

- Current environment (2025): Moderate real rates support reasonable valuations; sectors with strong near-term cash flows likely to outperform.

FX Market:

- Currencies backed by positive real rates tend to strengthen over time by attracting capital flows seeking real returns.

- Negative real rates create capital outflow risk, as seen during Turkey's recent experience where persistently negative real rates contributed to severe lira depreciation. Similarly, during Indonesia's 1997 crisis, negative real rates accelerated capital flight and currency collapse.

- Carry trade opportunities emerge when real rate differentials are significant.

- Current environment (2025): Developed market currencies with positive real rates (USD, EUR) likely to maintain strength against those with negative real rates.

Commodities:

- Historically inverse relationship with real rates (negative real rates often supportive).

- Storage costs relative to real rates impact positioning.

- Current environment (2025): Mixed outlook based on supply constraints versus monetary conditions.

Asset Class Sensitivity to Real Rate Changes Table:

| Asset Class | Impact of Rising Real Rates | Impact of Falling Real Rates | Key Sensitivity Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government Bonds | Negative (price decline) | Positive (price increase) | Duration, yield curve positioning |

| Corporate Credit | Moderately negative | Moderately positive | Credit spread cushion |

| Equities | Negative (especially growth) | Positive (especially growth) | Earnings growth, dividend yield |

| Real Estate | Negative | Positive | Leverage, rental growth |

| Commodities | Negative | Positive | Storage costs, carry |

| Emerging Markets | Highly negative | Highly positive | External financing needs |

Conclusion: Looking Beyond the Nominal Mirage

The distinction between nominal and real interest rates is far more than an academic exercise it represents the difference between apparent and actual economic conditions. As demonstrated through historical episodes from the 1970s stagflation to emerging market crises in Indonesia and Turkey, focusing solely on nominal rates without accounting for inflation has led to severe policy missteps and investment losses.

Monitoring real rates is essential for three key purposes:

Policy evaluation: Central banks must focus on real rates to accurately gauge monetary stance. Positive real rates typically indicate restrictive policy, while negative real rates suggest accommodation regardless of the nominal rate level.

Investment allocation: Investors need to assess real returns across asset classes and geographies to make informed decisions about where to deploy capital. What appears to be high nominal yields may disguise negative real returns that erode purchasing power.

Risk management: Understanding real rates helps identify potential economic vulnerabilities, currency risks, and asset bubbles before they fully manifest. Persistently negative real rates often precede financial instability.

In an era of increased inflation volatility and monetary policy uncertainty, the ability to look beyond nominal rates becomes even more critical. Investors who develop a sophisticated understanding of real rate dynamics gain a significant analytical advantage in navigating complex market environments.

While nominal rates capture headlines and dominate financial news coverage, real rates ultimately determine economic and investment outcomes. Policymakers, investors, and financial analysts who master real rate analysis will be better positioned to navigate the increasingly complex global economic landscape.

Nominal rates catch headlines. Real rates determine outcomes.