Liquidity Is Not Just Cash: Decoding the Lifeblood of Financial Markets

Liquidity is often described as the lifeblood of financial markets, and this metaphor holds true in practice. It refers to the capacity of the financial system to absorb trades and transactions smoothly essentially, how easily assets can be bought or sold without causing significant price disturbances. While many equate liquidity simply with cash on hand, in reality it encompasses a broader spectrum of assets and funding sources that keep markets functioning. From readily marketable securities to lines of credit, liquidity provides the vital flow that prevents markets from seizing up. Its importance cannot be overstated: even fundamentally sound institutions can be brought down by a liquidity crunch if they are unable to roll over funding or sell assets to meet short term obligations. This article decodes what liquidity truly means beyond just cash, examines its critical role in market stability, and discusses how policy frameworks strive to maintain liquidity in normal times and during crises.

Understanding Liquidity Beyond Cash

For analytical clarity, it is useful to distinguish between different forms of liquidity in the financial system. Liquidity is not just actual currency, but includes the ability to convert various resources into cash or credit quickly. Key dimensions of liquidity include:

- Market Liquidity: The ability to rapidly execute large transactions at a low cost and with limited price impact. In a highly liquid market, one can buy or sell assets (stocks, bonds, etc.) quickly at a fair price because there are ample buyers and sellers. Prices in such a market stay stable even when trading volumes spike, reflecting deep order books and tight bid-ask spreads.

- Funding Liquidity: The availability of cash or credit for institutions to meet their immediate obligations. This refers to an entity's capacity to raise funds (by selling assets, borrowing, or using credit lines) on short notice. The International Monetary Fund defines funding liquidity as "the ability of a solvent institution to make agreed upon payments in a timely fashion". In simple terms, a bank or firm's funding liquidity is its buffer to withstand cash outflows either it can meet its obligations or it cannot.

These two facets are closely interconnected. A strain in market liquidity can quickly morph into funding liquidity problems, and vice versa. For example, if market liquidity dries up (meaning an institution cannot sell assets without deep discounts), it may face cash shortages, triggering margin calls or urgent borrowing needs. This dynamic can create a vicious cycle: falling asset liquidity prompts fire sales and higher margin requirements, which further squeeze funding liquidity, forcing more sales in a self-reinforcing spiral. Conversely, if banks or investors lose access to funding, they may be forced to pull back from markets, worsening market liquidity. Understanding these dual aspects of liquidity is crucial, because a shock in one can rapidly transmit to the other in stressful times.

Liquidity: The Lifeblood of Markets

.png)

Liquidity underpins the smooth functioning of financial markets in good times and bad. In normal conditions, abundant liquidity allows investors to transact with confidence that they can enter or exit positions easily. This fosters efficient price discovery and lowers the cost of capital, as market participants know that trading frictions are minimal. A liquid market is a resilient market prices adjust in an orderly fashion as information changes, and isolated events are less likely to cause outsized swings. In contrast, illiquid markets are fragile. When liquidity is scarce, even small trades can lead to outsized price volatility, and investors demand a premium (an illiquidity premium) to compensate for the risk of not being able to trade when desired. In essence, liquidity greases the wheels of finance, enabling credit to flow and markets to allocate resources effectively.

Crucially, liquidity also has a systemic dimension: it supports financial stability. When markets are liquid and funding is readily available, institutions can handle shocks more easily by adjusting portfolios or borrowing as needed. But when liquidity evaporates, market functioning can break down. As recent events have shown, a sudden disappearance of liquidity can turn a market stress into a full-blown crisis. For instance, the stress in the UK government bond market in 2022 demonstrated that when liquidity vanishes, markets can become disorderly. Yields spiked and forced selling by pension funds cascaded into a broader rout a situation so severe that the Bank of England had to intervene to restore calm. Such episodes underscore that liquidity is not a trivial side issue; it is a central pillar of market confidence. Participants and policymakers alike monitor liquidity conditions as an indicator of market health. When liquidity is plentiful, markets function smoothly; when it dries up, markets can seize up and even solvent players may be unable to secure cash. In sum, robust liquidity is what separates a contained disturbance from a wider market contagion.

Liquidity in Times of Crisis

Financial crises have repeatedly illustrated that liquidity can disappear suddenly and brutally, with devastating effects. In the 2008 global financial crisis, liquidity stress was at the core of the turmoil. Funding markets that banks relied on (like the interbank lending and commercial paper markets) froze virtually overnight, as trust between institutions eroded. Banks that were otherwise solvent found themselves unable to roll over short-term debts or sell assets without huge losses. This forced fire sales of assets at depressed prices, further worsening the situation. Central banks had to step in with massive emergency lending and asset purchases to prevent wholesale banking collapse. A key lesson from 2008 was that liquidity risk can fell institutions just as surely as insolvency in fact, illiquidity was the immediate trigger for the failure of major firms that year. Since then, regulators have focused intensely on ensuring banks hold larger liquidity buffers (e.g. high-quality bonds that can be sold or pledged) to withstand such shocks.

More recent crises show that liquidity vulnerabilities are not confined to banks. In March 2020, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, even the U.S. Treasury market typically the world's most liquid financial market experienced a sudden liquidity failure. Investors across the globe rushed to raise cash, dumping even safe-haven Treasury bonds. Treasury yields spiked dramatically within days, as buyers evaporated and selling pressures soared. In fact, the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield jumped by an astonishing 64 basis points from March 9 to 18, 2020, an unusual surge for such a short period. This dislocation was driven not by a loss of creditworthiness, but by pure liquidity stress various funds and foreign holders needed cash immediately and struggled to find buyers. The U.S. Federal Reserve responded with unprecedented speed and scale, purchasing roughly $1 trillion of Treasuries in the first quarter of 2020 to inject liquidity and stabilize the market. Those actions quickly reversed the spike in yields and restored order, underscoring the critical role of central banks in backstopping market liquidity during extreme events.

Another case in point was the UK gilts crisis of 2022 mentioned earlier. There, a sharp rise in yields (partly due to anticipated policy changes) led to margin calls for pension funds employing leverage. This created a feedback loop where funds had to sell more gilts to meet margin further driving down prices and draining liquidity. The situation spiraled until the central bank stepped in as a buyer of last resort. Within days of the Bank of England's intervention, calm returned and yields moderated. The episode was a stark reminder that liquidity issues can emerge in unexpected corners of the financial system (in this case, pension fund strategies) and can amplify market stress rapidly.

These crises highlight a few key points. First, solvency and liquidity are distinct but intertwined a solvent institution or market can be pushed into distress by a liquidity freeze. Second, liquidity crises tend to feed on themselves (the liquidity spiral effect discussed earlier), requiring decisive intervention to break the cycle. Third, central banks and public authorities have an indispensable role as lenders (and market-makers) of last resort when private liquidity flees. Walter Bagehot's 19th-century dictum to lend freely at a high rate against good collateral in a panic remains a cornerstone of crisis management. Indeed, during both 2008 and 2020, central banks around the world flooded their systems with liquidity to prevent collapse, reflecting this principle. Lastly, every crisis reveals new channels for liquidity risk: today, it is not just banks we worry about, but also money-market funds, hedge funds, and other non-bank players that can propagate liquidity shortfalls. Recognizing these channels is essential for devising robust safeguards.

Policy Implications: Managing Liquidity Strategically

Policymakers and institutions have learned from experience that active liquidity management is critical for financial stability. In practice, this means monitoring liquidity conditions, preparing tools to alleviate strains, and implementing rules that reduce the likelihood of liquidity droughts. Striking the right balance is challenging: too little liquidity can trigger crises, yet too much liquidity for too long can encourage reckless risk-taking or asset bubbles. Senior financial officials therefore approach liquidity as a strategic policy variable, adjusting it as conditions warrant.

Central banks serve as the fulcrum of liquidity management. In normal times, they manage the overall availability of money and credit (through interest rates and open market operations) to foster stable economic growth. In stressed times, they act as providers of liquidity of first and last resort. Central banks routinely stand ready to provide emergency funding to banks facing short-term cash shortages (against proper collateral) a classic lender-of-last-resort function. They have also developed new facilities to support market liquidity directly. For example, the U.S. Federal Reserve and other major central banks now maintain standing repo facilities and swap lines to inject dollar liquidity globally if markets seize up, a backstop that can prevent panic from spreading. During the 2020 turmoil, such tools were deployed swiftly. However, central bankers must constantly weigh trade-offs: as they tighten monetary policy today to combat inflation, they are aware that rapid rate hikes and balance sheet reduction can drain liquidity from markets. Indeed, after years of abundant liquidity, the recent transition to higher rates has been accompanied by pockets of reduced market liquidity and greater volatility across asset classes. Policymakers are treading carefully, trying to restore price stability without inadvertently causing a liquidity crunch in critical markets.

Regulators and financial institutions also play a major role through prudential liquidity requirements. In the wake of the 2008 crisis, regulators introduced robust liquidity standards so that banks would be self-insured against short-term liquidity shocks. Foremost among these is the Basel III Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), which mandates that banks hold enough High-Quality Liquid Assets (like cash, government bonds, and other easily sellable securities) to cover their expected net cash outflows for 30 days under stress. The aim is to ensure that even if funding markets dry up, each bank has a liquidity buffer it can immediately tap (by selling assets or borrowing against them) to meet withdrawals or other needs. Complementing this, the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) requires banks to maintain a stable funding profile over a one-year horizon, discouraging overreliance on short-term hot money. These tools have significantly improved banks' resilience by forcing them to internalize liquidity risk in their balance sheet management. Major institutions now run regular stress tests on their liquidity positions and are required to have contingency funding plans.

At the same time, authorities recognize that regulations must calibrate liquidity and market efficiency. For instance, while higher liquidity buffers make individual banks safer, they could, in aggregate, reduce the amount of cash or Treasuries circulating in the market. Similarly, restrictions on proprietary trading and tighter capital rules after 2008 prompted many large banks and dealers to scale back market-making activities. Studies have indicated that such post-crisis rules (e.g. the Volcker Rule in the US) have in some cases reduced the capacity of intermediaries to provide liquidity in secondary markets. In corporate bond markets, for example, dealer inventories are leaner and trading can be thinner than before, which might make these markets more prone to bouts of illiquidity during stress. Policymakers are debating these trade-offs: how to maintain strong safeguards without unduly impairing day to day market liquidity. Some measures, like incentivizing central clearing and improving transparency, aim to bolster liquidity by increasing market participants and information flow. Ultimately, effective liquidity management requires a holistic view one that spans banks and non-banks, domestic and international markets, and normal and stress conditions.

Conclusion: Sustaining Liquidity for Future Stability

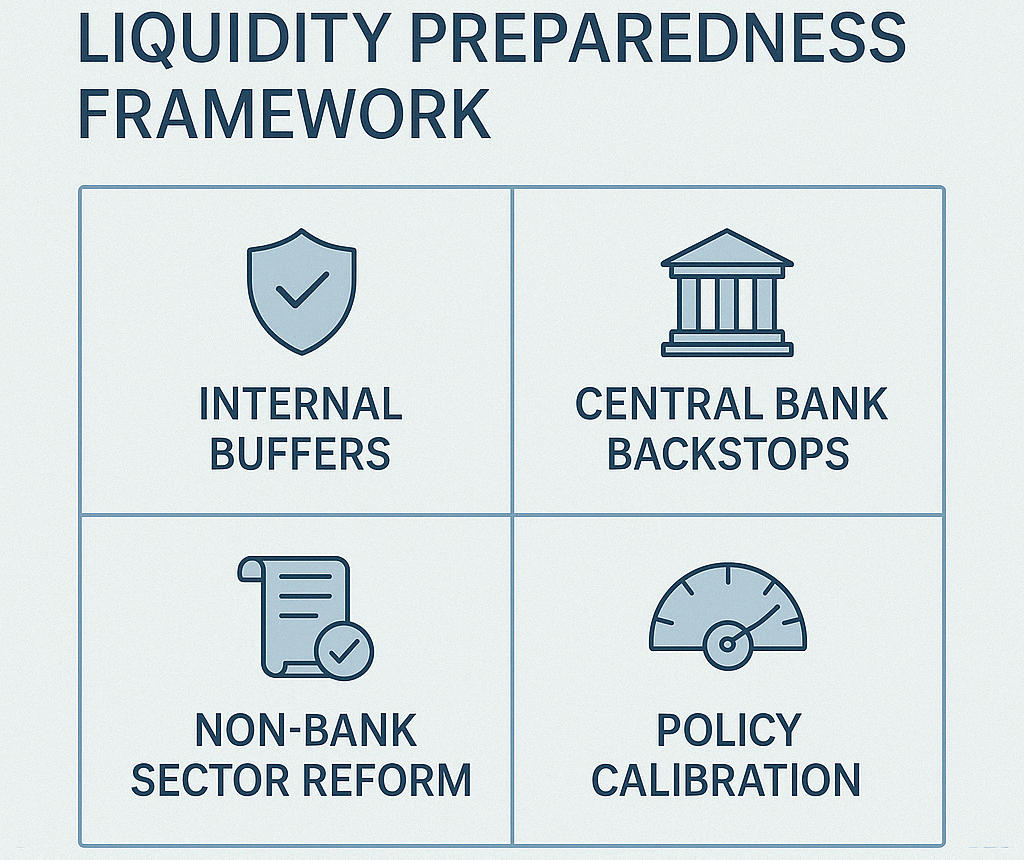

Liquidity, in all its forms, remains the lifeblood of the financial system. It is a fundamental enabler of economic activity, confidence, and stability. The analysis above makes clear that liquidity is much more than just cash it is an ecosystem of markets and funding channels that must be nurtured and safeguarded. A well-functioning financial system is one where liquidity is ample enough to absorb shocks but not so excessive as to sow the seeds of the next crisis. Achieving this balance is a central task for policymakers and institutions as they look ahead. In summary, maintaining a robust liquidity environment will require vigilance and proactive strategy. Key forward-looking priorities include:

-

Bolster Liquidity Buffers and Risk Management: Banks and other financial institutions should continue to hold robust liquidity buffers and regularly test their ability to withstand severe outflows. Supervisors must ensure that these buffers (e.g. under LCR and NSFR) remain credible and that institutions plan for contingent funding during extreme events. Strong internal liquidity risk management, including stress simulations and early-warning indicators, is essential so that firms can react before a liquidity squeeze becomes fatal.

-

Enhance Central Bank Liquidity Backstops: Policymakers should maintain and refine central bank tools for liquidity provision. This includes standing facilities (such as repo operations or swap lines) that can be activated quickly to stabilize key markets, as well as clear communication of lender of last resort capabilities to bolster confidence. Fast, decisive intervention can stop a localized liquidity problem from cascading, so central banks need the operational readiness and flexibility to act when needed whether to support an individual institution or to un-freeze an important market.

-

Address Liquidity Risks Beyond the Banking Sector: A forward looking liquidity strategy must broaden its scope to non-bank intermediaries. Regulators are increasingly focusing on liquidity mismatches in areas like money market funds, open end investment funds, and other dollar funding markets outside traditional banks. Reforms such as requiring funds to have liquidity management tools (e.g. swing pricing, redemption notice periods) and closer monitoring of hedge fund leverage can reduce the likelihood that an unforeseen shock in these areas leads to a systemic liquidity crunch. In addition, improving the resilience of market infrastructure (for example, exchanges and clearinghouses) will help ensure that market liquidity can be maintained under stress.

-

Calibrate Policy to Market Liquidity Conditions: Finally, authorities should integrate liquidity considerations into macroeconomic and regulatory decision making. As central banks normalize monetary policy after years of extraordinary accommodation, they must gauge the impact on market liquidity and be ready to pause or adjust if critical markets show signs of dysfunction. Similarly, regulatory adjustments should be approached carefully, with input from market participants, to avoid unintended liquidity withdrawals. In quiet times, maintaining some constraints on exuberance (through macroprudential measures) can prevent liquidity fueled asset bubbles. In turbulent times, temporarily relaxing certain requirements or utilizing central bank balance sheets might be warranted to keep core markets liquid.

By pursuing these strategies, policymakers and financial leaders can better future proof the system against liquidity shocks. The goal is to ensure that when the next surprise comes and history suggests it will the financial system has enough liquidity shock absorbers to cope, and that any necessary official intervention is effective and orderly. In conclusion, liquidity may be an invisible attribute in benign times, but it is absolutely pivotal when stress hits. Treating liquidity as a strategic public good, to be managed and protected, will remain a top-tier priority for macro-financial policy. With prudent preparation and agile response tools, the lifeblood of financial markets can continue to circulate even under duress, sustaining confidence and stability in the global financial system.