Is Traditional Monetary Policy Dead? Navigating Liquidity Traps in a Post-Crisis World

This article critically examines the diminishing effectiveness of traditional monetary policy tools particularly interest rate cuts in the face of persistent economic stagnation and structural challenges following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. It explores the emergence of liquidity traps, where near-zero interest rates fail to stimulate investment or consumption, and introduces the concept of shadow rates as a more accurate reflection of monetary accommodation under unconventional policy regimes. The piece discusses the rise and limitations of quantitative easing (QE), highlighting its unequal impacts on asset prices versus the real economy. It contrasts the policy responses of the U.S. Federal Reserve and Bank Indonesia, emphasizing the need for tailored, pragmatic strategies in emerging markets. The article concludes by advocating for a multidimensional monetary policy framework that incorporates tools like yield curve control, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), and closer fiscal-monetary coordination, arguing that adaptation not abandonment of central banking is essential in the post-crisis world.

The Diminishing Returns of Interest Rate Cuts

In the wake of successive global financial crises, central banks worldwide face an uncomfortable reality: the traditional monetary policy playbook appears increasingly ineffective. The once-reliable mechanism where lowering interest rates stimulated borrowing, investment, and consumption now produces diminishing returns even as rates approach or cross into negative territory. For emerging economies like Indonesia, understanding this paradigm shift is not merely academic but existential to their economic sovereignty and growth prospects.

As economist Larry Summers has warned, global markets now "seem to price in a return to secular stagnation, or Japanization." In this environment, excess savings persist despite record deficits and unprecedentedly low real rates, yet growth remains disappointing. Most troubling, as Summers notes, "markets do not expect any country in the industrial world to hit a 2% inflation target. Despite unprecedentedly low interest rates...growth has been tepid."

The Transformation of Monetary Policy

Throughout most of the 20th century, central banks operated under a relatively straightforward model. When economies slowed, they cut interest rates to encourage borrowing and spending. This mechanism functioned as the primary lever for managing economic cycles, with remarkable consistency.

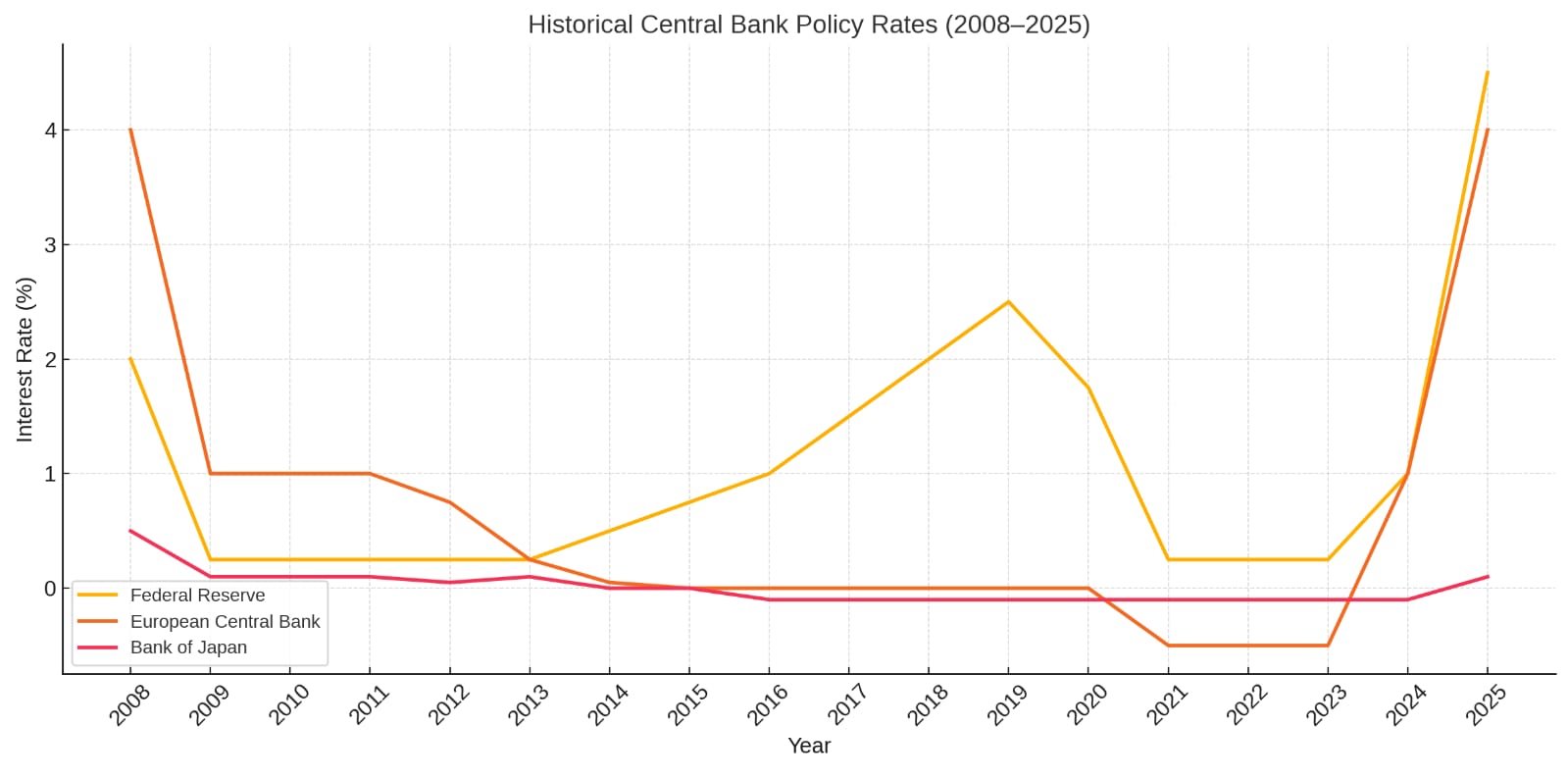

However, the landscape has fundamentally changed. Since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, major economies have experienced what economists call "Japanization" a condition of persistent low growth, inflation, and interest rates despite extraordinary monetary stimulus. Japan pioneered this territory in the 1990s, but the phenomenon has since become a global concern.

"The traditional transmission mechanism has been severely weakened," notes former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke in his analysis of post-crisis monetary effectiveness. "At zero or near-zero rates, additional cuts fail to generate the economic response we'd historically expect."

When Liquidity Traps Ensnare Economies

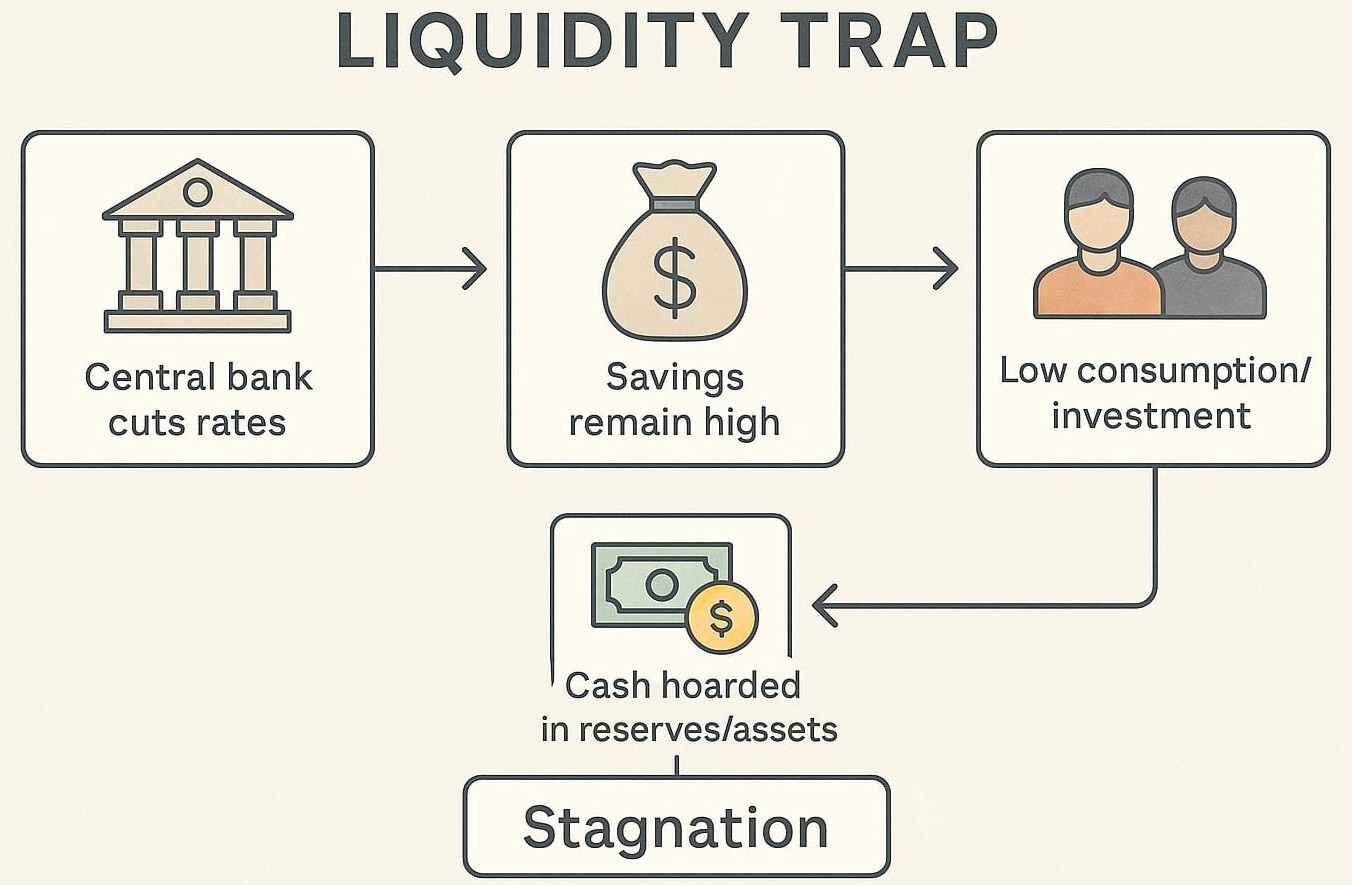

A liquidity trap occurs when interest rates approach zero, yet savings remain high while consumption and investment stagnate. In this environment, economic agents prefer holding cash rather than spending or investing even when central banks inject massive liquidity into the system.

This phenomenon has deep historical roots, including the Great Depression of the 1930s. But its modern manifestations Japan's "Lost Decades" beginning in the 1990s and the global economy's tepid response to unprecedented stimulus after 2008 reveal how entrenched these conditions can become.

The mechanics are straightforward but pernicious: When nominal interest rates hit the zero lower bound (ZLB), central banks lose their primary tool for stimulating demand. Money created through loose monetary policy simply accumulates in bank reserves or financial assets rather than circulating through the real economy, creating a liquidity trap from which traditional policy cannot easily escape.

Shadow Rates: Measuring Policy When Conventional Metrics Fail

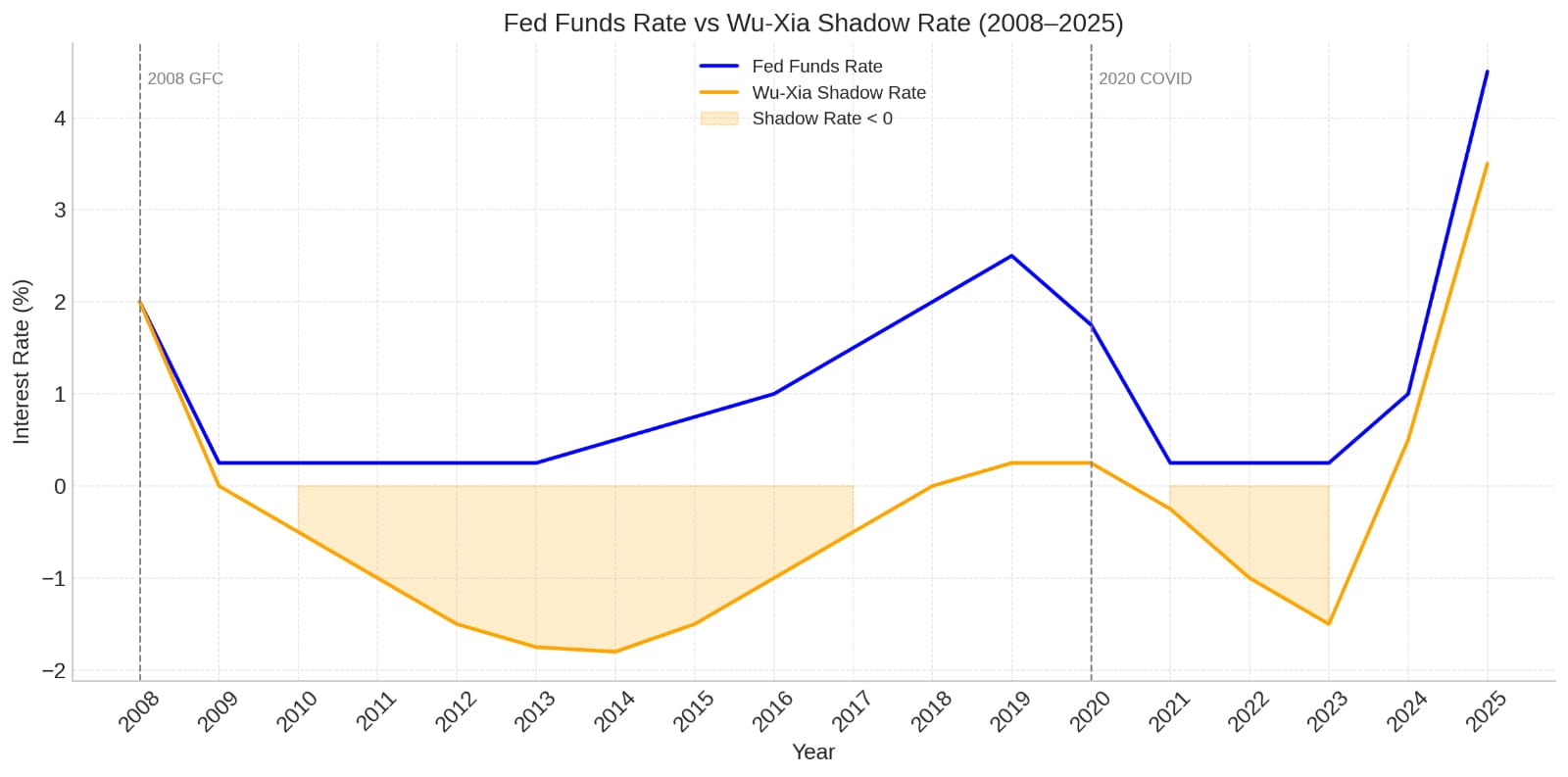

With policy rates constrained by the zero lower bound, economists have developed alternative measures to gauge the true stance of monetary policy. Shadow rates conceptualized by economists Wu and Xia attempt to capture the effective interest rate when accounting for unconventional policies like quantitative easing.

As the Atlanta Fed explains, "Unlike the observed short-term interest rate, the shadow rate is not bounded below by 0%." When the shadow rate exceeds 0.25%, it simply equals the actual rate; but below that bound it reflects QE, guidance, and other tools. During the Fed's prolonged zero-rate period (December 2008–December 2015 and again March 2020–March 2022), the Wu-Xia shadow rate swung significantly negative, revealing a monetary stance far more accommodative than the nominal 0–0.25% rate suggested.

For emerging markets like Indonesia, these shadow dynamics matter tremendously. BIS research shows that U.S. monetary policy including its shadow stance has driven EM policies since 2012. Fed accommodation has been associated with emerging market central banks keeping policy rates on average 150 basis points lower than domestic fundamentals alone would suggest. In effect, even if Bank Indonesia maintains a positive policy rate, global "shadow" easing spills over, influencing capital flows and market rates domestically.

Beyond Interest Rates: The Unconventional Arsenal

As conventional tools lost potency, central banks deployed an array of unconventional policies, with quantitative easing (QE) at the forefront. Unlike traditional interest rate management, QE involves central banks purchasing assets typically government bonds to inject liquidity directly into financial markets.

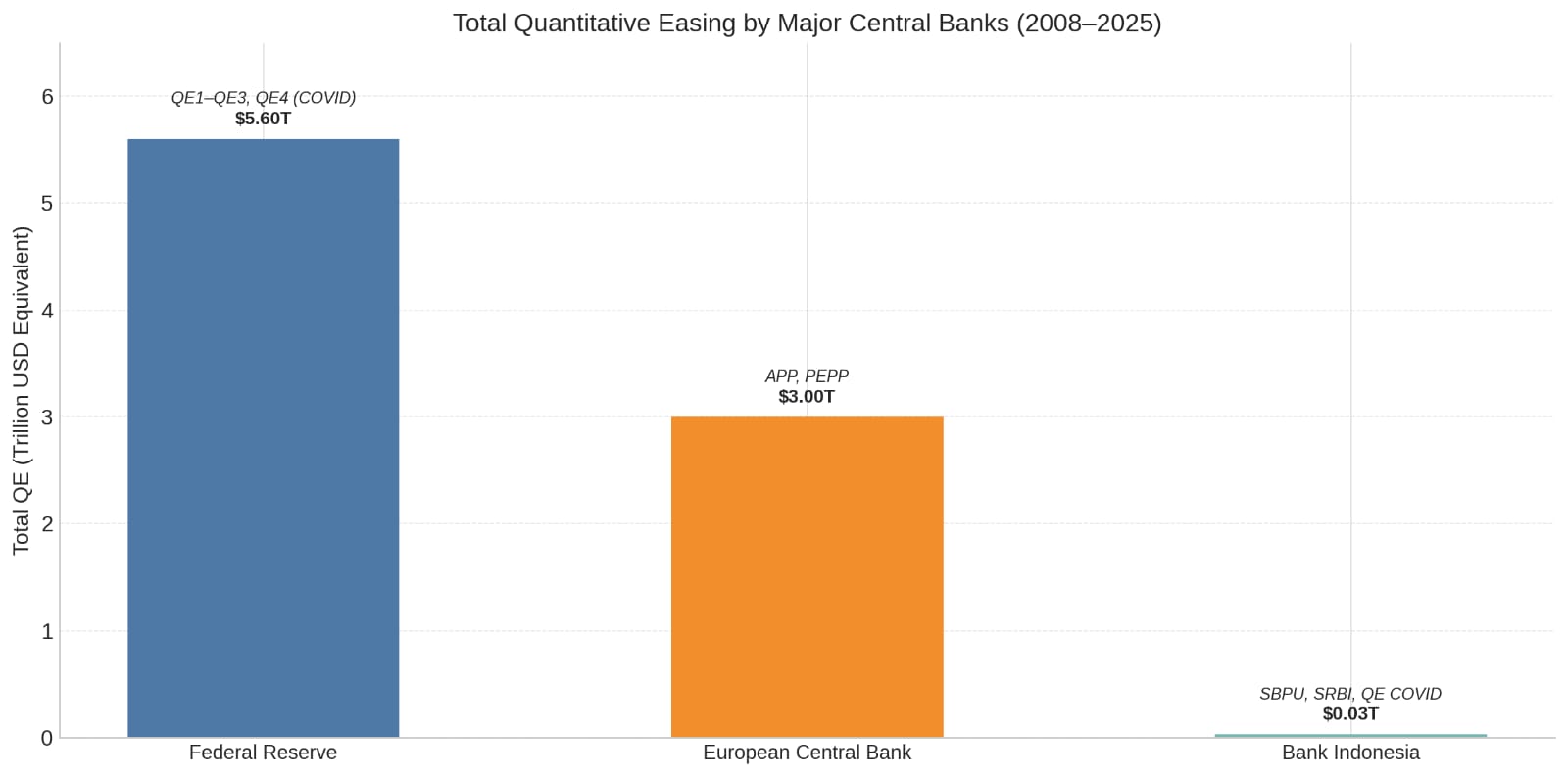

The scope of these interventions has been unprecedented. The Federal Reserve's QE programs between 2008 and 2023 amounted to over $5.6 trillion in Treasury purchases alone, deployed in successive waves (QE1, QE2, QE3) after 2008 and again in 2020–21 to counteract the pandemic downturn. Similarly, the European Central Bank's asset purchase programs have accumulated approximately €2.78 trillion in securities by March 2025.

These programs work primarily through portfolio rebalancing: as central banks purchase long-term government securities, investors pivot toward corporate bonds and equities, thereby lowering yields across asset classes and theoretically stimulating investment.

In Indonesia, Bank Indonesia (BI) adopted its own version of these measures during the COVID crisis. In 2020, under emergency authorization, BI purchased IDR473.4 trillion of government bonds directly (approximately 4.7% of GDP) to finance pandemic relief. This "burden sharing" with fiscal authorities helped keep yields low for the recovery program without triggering market disruption.

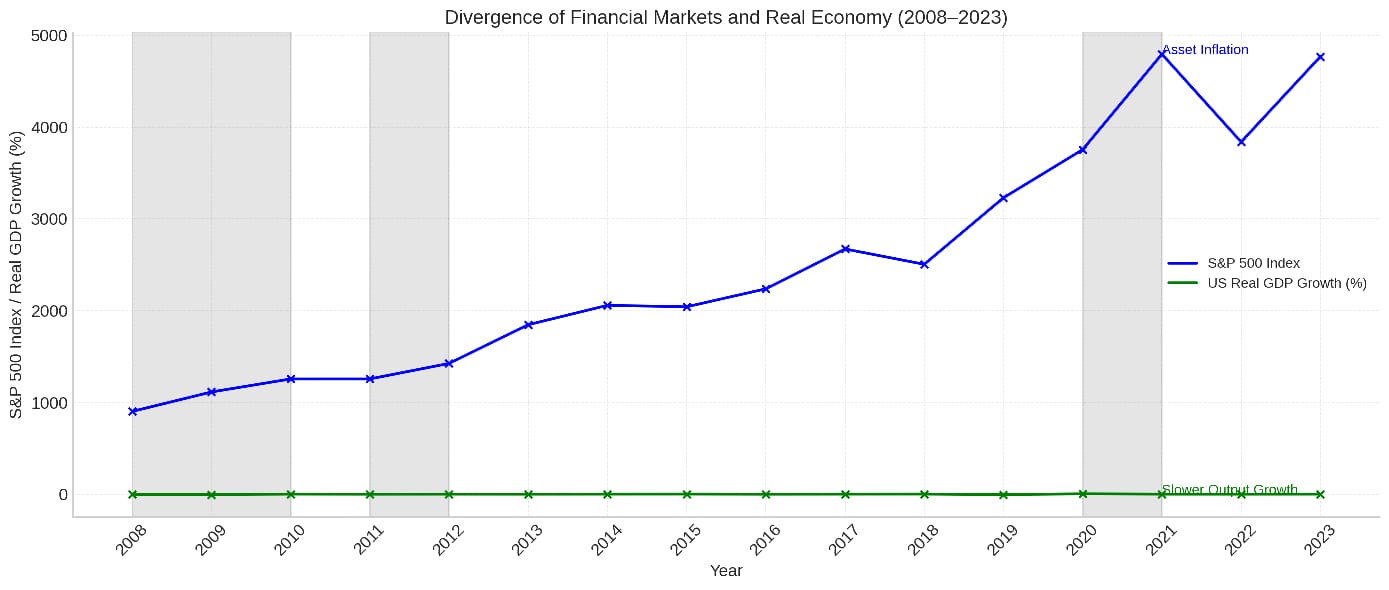

However, these programs revealed significant limitations. QE often boosted financial asset prices without proportionately benefiting the real economy, thereby exacerbating wealth inequality. Moreover, its effectiveness diminished with each successive iteration as the underlying structural weakness in demand persisted.

The Multi-Faceted Challenge for Today's Central Bankers

Central banks now navigate a landscape fragmented by geopolitical tensions, reversals in globalization, and persistent structural inflation pressures. The U.S.-China strategic competition has accelerated dedollarization efforts in many economies, while recent studies note a troubling "selective decoupling" in trade flows for example, the EU has effectively severed energy ties with Russia, while also beginning to curb high-tech exposure to China.

Such fragmentation creates asymmetric shocks that disrupt previously stable import-export relationships. The risks are substantial: simulation models suggest that a 50% reduction in imports of critical inputs from major suppliers could cut industrial output by approximately 5–7% in affected sectors. Central banks must now contend with these supply-side inflation pressures that lie partly outside their traditional control mechanisms.

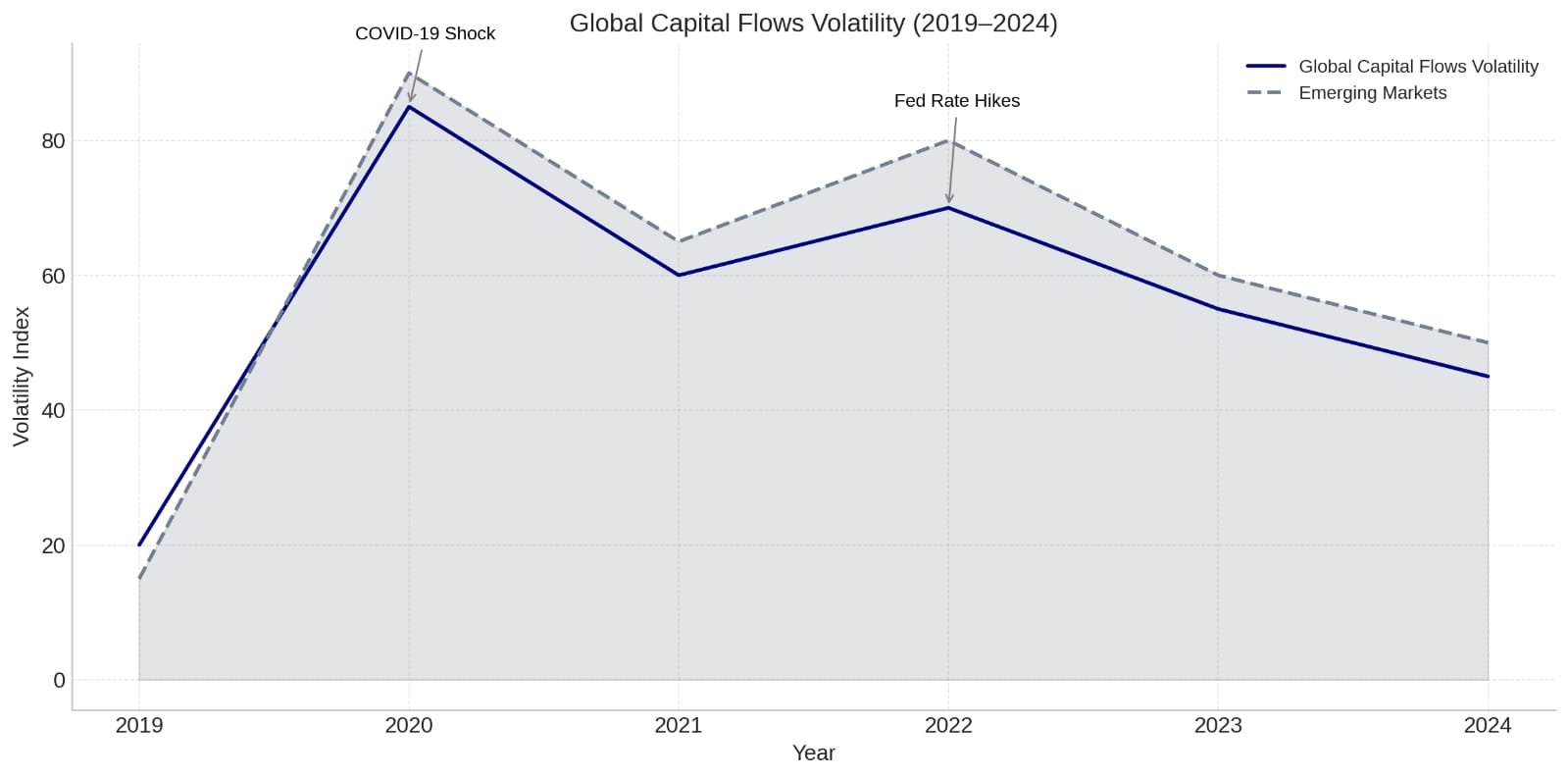

Financial fragmentation and capital-flow volatility compound these challenges. As trade blocs form and global bond markets segment, yield differentials between countries can widen dramatically. After the pandemic, some economies (notably the U.S.) tightened faster than others, triggering sharp capital reallocations and exchange-rate turbulence. In this environment, central banks especially in emerging markets often face a painful choice between stabilizing their currency or supporting economic growth.

Perhaps most concerning is the emergence of structural inflation price increases driven by non-monetary forces such as supply constraints, climate transition costs ("greenflation"), and trade barriers. These pressures undermine the traditional monetary transmission mechanism. Policymakers find themselves forced to maintain tight policy even when growth is soft, simply to anchor inflation expectations.

Central bank credibility itself is at stake after years of emergency easing that inflated asset prices and corporate debt levels. As Summers has cautioned, "extremely low and negative real interest rates...set the stage for the perpetuation of zombie enterprises and the perpetuation of financial bubbles." If inflation expectations become unanchored, or financial instability erupts, public trust in monetary authorities could erode substantially.

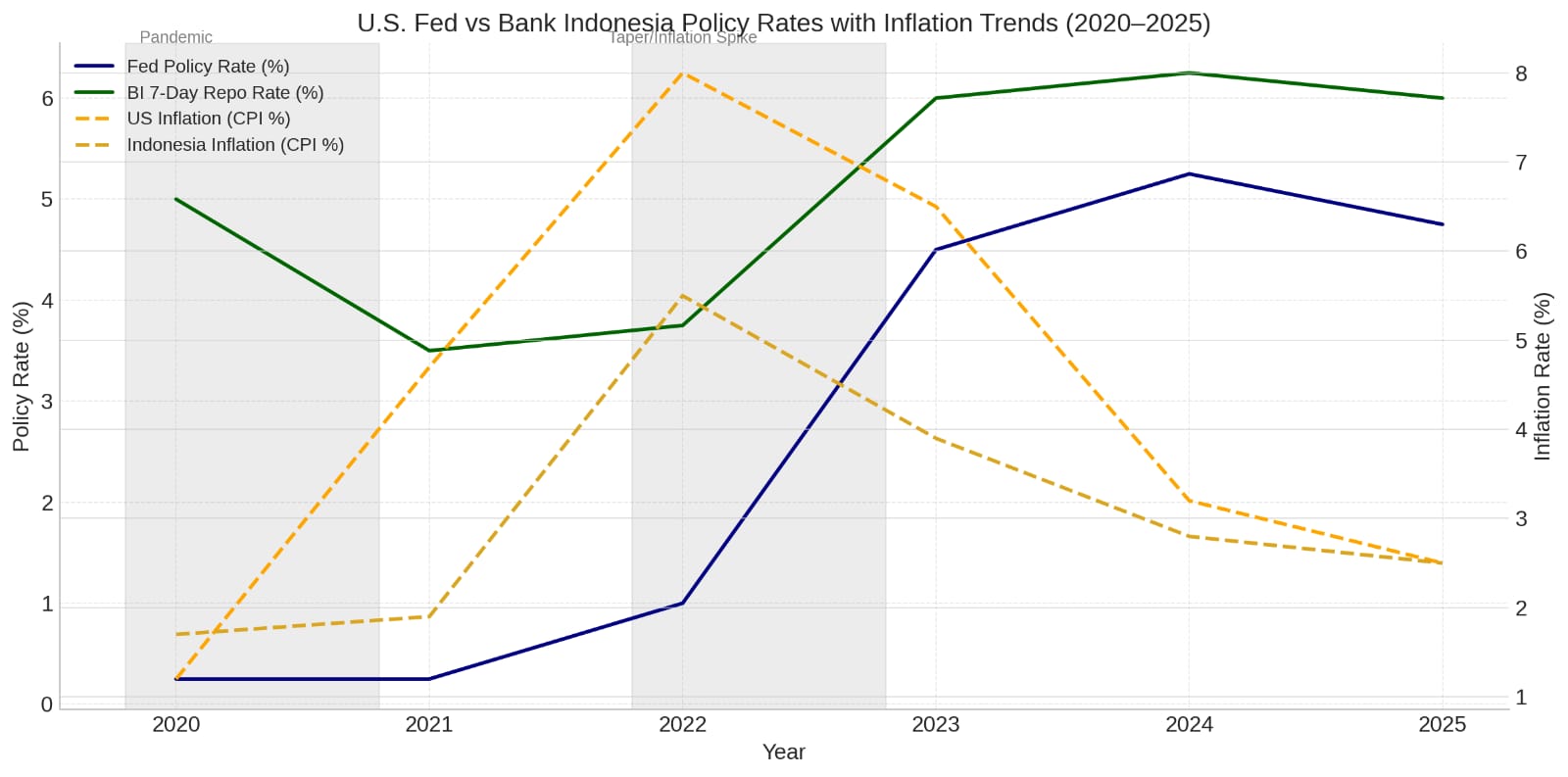

Divergent Paths: The Federal Reserve and Bank Indonesia

The Federal Reserve's journey illustrates the complexity of modern monetary management. After deploying zero interest rates and multiple QE rounds post-2008, the Fed's attempt to normalize policy in 2013 triggered the "taper tantrum," sending shockwaves through emerging markets. Yet by 2022, facing resurgent inflation, the Fed executed one of its most aggressive tightening cycles in history.

Starting from near zero, the Federal Reserve raised rates seven times in 2022 and four times in 2023, lifting the federal funds target from 0–0.25% to 5.25–5.50% by late 2023 the fastest tightening cycle in decades. This dramatic pivot reflected the Fed's determination to combat 40 year high inflation, even at the risk of economic slowdown. The Fed's own analysis acknowledges that, due to earlier QE and forward guidance, monetary policy had become "substantially tighter" than the nominal funds rate alone would suggest.

Bank Indonesia, meanwhile, has pursued a more conservative approach focused on stability. Rather than mimicking advanced economy strategies of ultra-low rates, it has generally maintained positive real interest rates while innovating through selective interventions. During the COVID-19 crisis, BI did cut its rate to a record low 3.5% by mid-2020 and coordinated bond purchases with the government, but these actions were carefully calibrated to preserve price stability.

More recently, as Indonesian inflation has remained tame (below the 1.5–3.5% target band at just 1.6% in December 2024), BI has balanced growth and stability objectives. In January 2025, it surprised markets by cutting its 7-day reverse repo rate by 25 basis points to 5.75%. Governor Warjiyo explained that slowing growth amid subdued inflation allowed this easing "to create a better growth story." Yet BI has remained vigilant about rupiah stability, intervening in currency markets when necessary to prevent excessive depreciation.

As MUFG economists note, BI's policy "restrictiveness has started to act as a drag on growth," suggesting that targeted easing is appropriate while inflation remains contained. This pragmatic approach demonstrates that emerging markets must chart their own course rather than simply following advanced economy templates.

Reimagining Monetary Policy for the Future

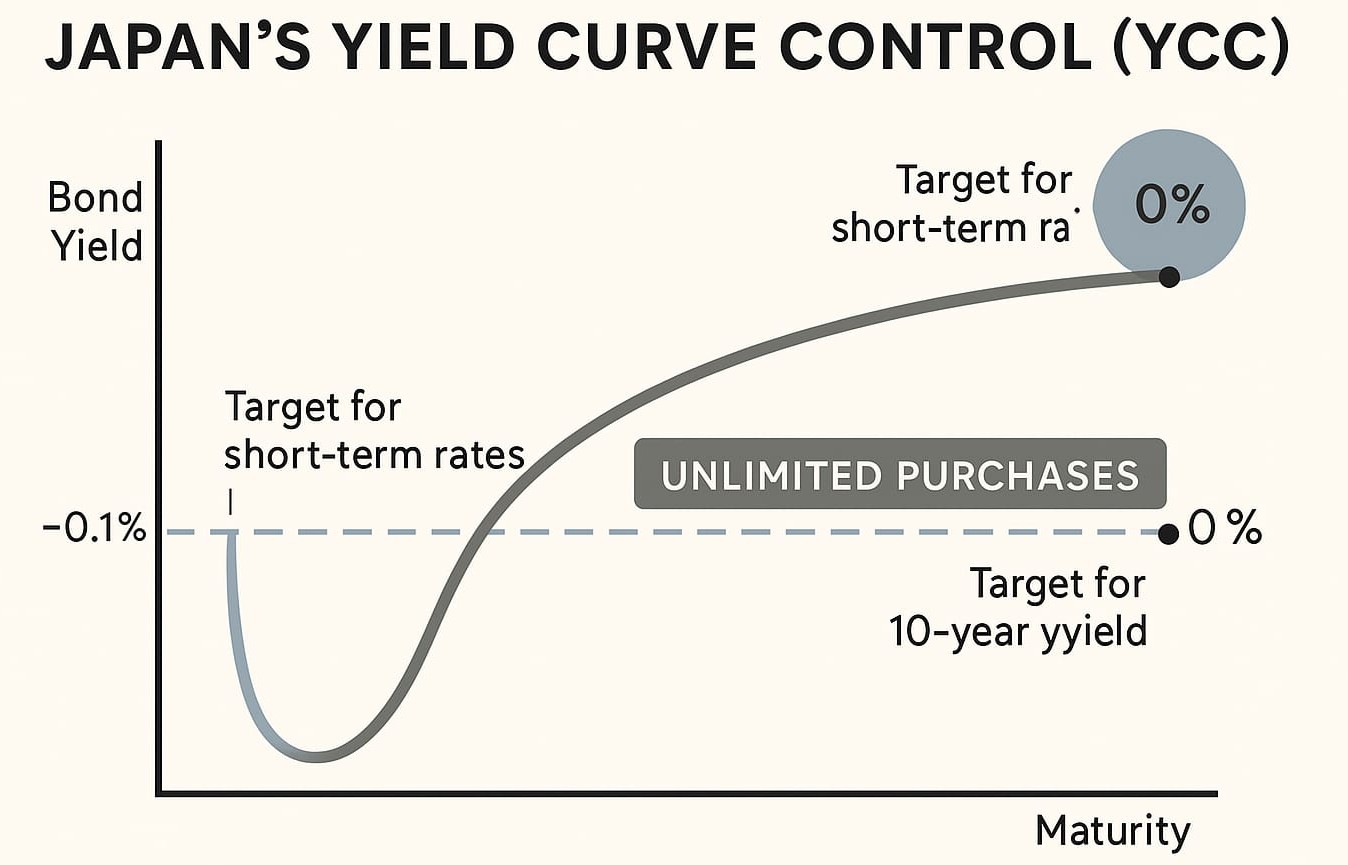

As traditional approaches show their limitations, central banks are exploring new frameworks. Japan's Yield Curve Control (YCC), which targets specific long-term interest rates rather than short-term rates or quantity of money, represents one innovation. Since 2016, the Bank of Japan has capped its 10-year government bond yield near 0% through unlimited purchase commitments, effectively sidestepping the zero bound on long-term rates (though at the cost of potential balance sheet risks).

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) offer another frontier for policy innovation. While primarily motivated by payment system considerations, CBDCs could eventually alter monetary transmission by allowing central banks to interact more directly with households and businesses. Interest is substantial: a 2021 BIS survey found that 86% of central banks are actively researching CBDCs, with 60% conducting experiments and 14% already piloting such programs.

Sector-targeted liquidity facilities represent yet another evolution. During the pandemic, the Federal Reserve created specialized programs like the Main Street Lending Facility to channel credit directly to small and mid-sized firms. This targeted approach focusing on specific sectors rather than broad market conditions may become more common as traditional channels prove less reliable.

More fundamentally, the strict separation between monetary and fiscal policy sometimes called "monetary dominance" is being reconsidered. The pandemic response saw unprecedented coordination between central banks and treasuries worldwide, raising questions about whether such collaboration should become a permanent feature of macroeconomic management.

Policy Imperatives for a Post-Traditional World

For developed economies trapped in low-rate environments, the path forward requires diversification beyond interest rate management. This means developing frameworks for judicious monetary-fiscal coordination without compromising central bank independence, while also addressing structural impediments to growth.

Advanced economy central banks should acknowledge that traditional levers are constrained and embrace a multi-pronged strategy. This could include tolerating temporarily higher inflation when necessary to encourage investment, while reinforcing long-term commitment to price stability. Practically speaking, they should remain prepared to implement QE or YCC during deep slumps, while simultaneously strengthening macroprudential regulations to mitigate the financial stability risks of prolonged low rates.

Emerging markets like Indonesia face a different imperative: building resilience against external monetary shocks while developing tailored approaches to their specific economic conditions. With Indonesian inflation at just 1.6% in December 2024 (near the bottom of the 1.5–3.5% target range), Bank Indonesia has room for continued measured easing to support growth, but must remain vigilant about external vulnerabilities.

The comprehensive strategy should include:

-

Maintaining adequate foreign exchange reserves to buffer against capital flow volatility

-

Deploying macroprudential tools to support targeted credit growth without fueling overheating

-

Deepening domestic capital markets to reduce external financing dependencies

-

Strengthening regional financial cooperation through initiatives like the Chiang Mai Initiative

-

Promoting coordination with fiscal authorities on structural reforms that address productivity challenges

Conclusion: Adaptation, Not Abandonment

Traditional monetary policy is not dead, but it requires reinvention. The interest rate tool will remain in central banks' arsenals, but as one component in an increasingly diverse and sophisticated toolkit. Countries that fail to adapt their monetary frameworks risk prolonged economic stagnation or heightened vulnerability to external shocks.

As Summers aptly observes, the first step in meeting new challenges is to recognize them. This means accepting that even the most aggressive rate cuts may not guarantee growth, and being ready to supplement them with balance-sheet policies, regulatory measures, and closer fiscal coordination.

For Indonesia and other emerging economies, the challenge is particularly nuanced learning from advanced economies' experiences while recognizing their different circumstances. Their success will depend not on mechanically following developed-economy templates but on crafting innovative approaches that address their specific economic structures, development needs, and vulnerability points.

As former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King observed, "Central banking is not so much a science as an art requiring continuous adaptation." In a post-traditional monetary world, that adaptation has never been more necessary or more challenging.