industries

energy

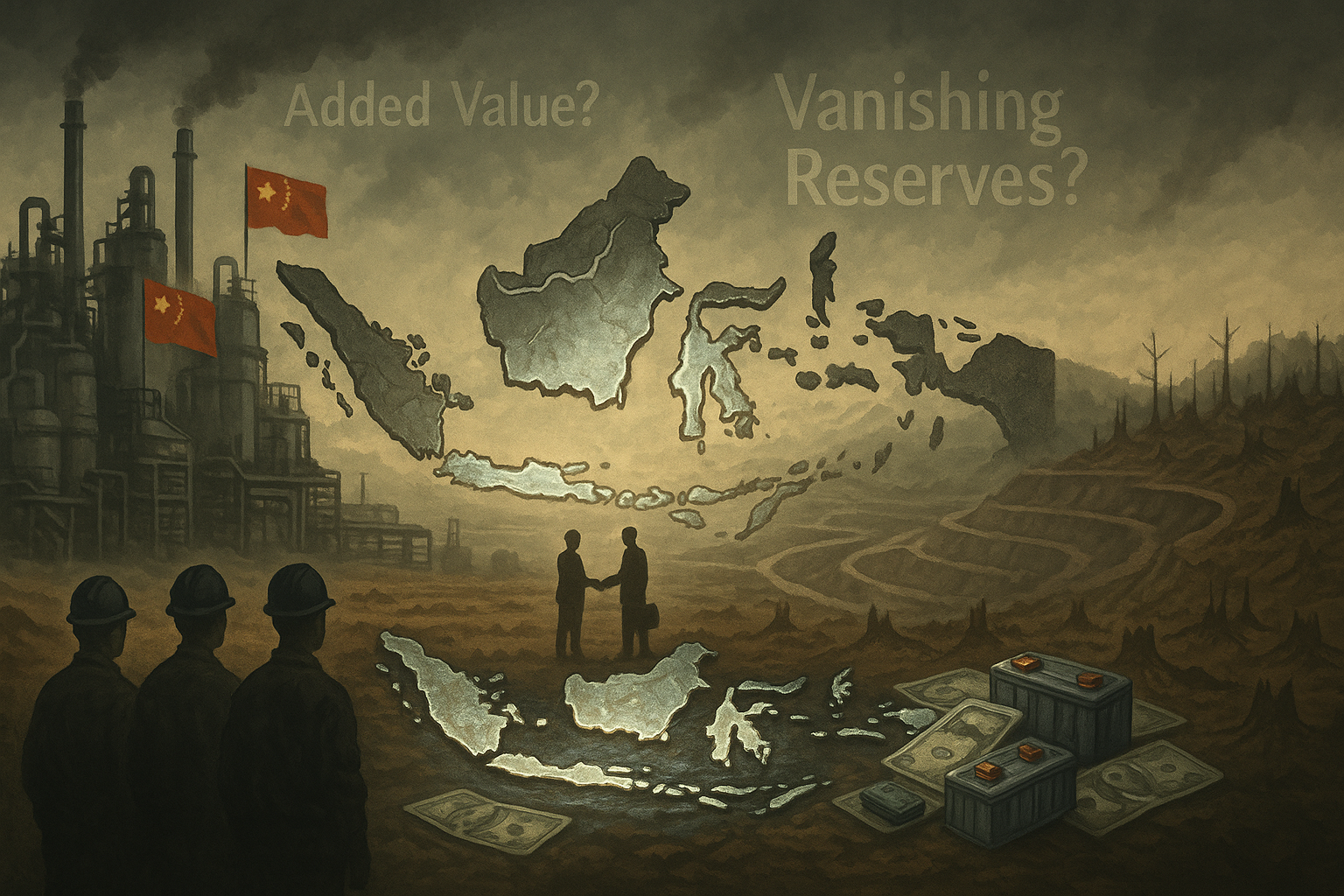

Indonesia's Downstream Nickel Strategy: Battery Supply Chain Sovereignty or Resource Trap?

By SD

June 15, 2025

10 min read

The article critically examines Indonesia’s ambitious downstream nickel strategy, which aims to transform the country from a raw material exporter into a key player in the global electric vehicle and battery supply chain. While Indonesia has significantly increased its nickel export value and attracted massive foreign investment particularly from China, the strategy faces major challenges, including environmental degradation, technological dependency, inequitable benefit distribution, and potential resource depletion. The analysis raises the question of whether Indonesia is truly achieving economic sovereignty or falling into a resource trap, urging a shift toward cleaner technologies, stronger domestic capacity, and more equitable, sustainable industrial development.

Indonesia commands the world's largest nickel reserves, holding approximately 55 million metric tons as of 2023. These vast resources, primarily concentrated in Sulawesi and North Maluku, have positioned Indonesia as the dominant global producer, accounting for 51% of world nickel mine production. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, Indonesia controls 42% of global nickel reserves, granting the country unprecedented leverage in global nickel markets.

The scale of Indonesia's dominance becomes clear when examining production trends over the past decade:

| Year | Indonesia Production (Mt) | Global Production (Mt) | Indonesia's Share (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 0.23 | 1.6 | 14 |

| 2015 | 0.45 | 2.0 | 23 |

| 2020 | 1.04 | 2.5 | 41 |

| 2022 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 49 |

| 2023 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 51 |

This mineral wealth has gained strategic importance as global nickel demand surges, driven primarily by electric vehicle batteries and renewable energy storage systems. Recognizing this opportunity, the Indonesian government has implemented ambitious policies to capture greater value from its resources, moving decisively away from raw material exports toward comprehensive downstream processing.

The significance of this transformation extends far beyond economics. Through nickel downstreaming, "the government attempts to increase added value, investment, GDP, exports and job creation," as research by Bahlil Lahadalia and colleagues demonstrates. This approach directly challenges the traditional global division of labor, where resource-rich developing countries export raw materials while developed economies capture value-added processing and manufacturing.

Indonesia's strategic timing proves particularly astute given rising global demand. The International Nickel Study Group forecasts global nickel demand will reach 3.514 million tons in 2025, with Asia—particularly Indonesia and China—driving production growth. As nickel becomes increasingly critical for both traditional stainless steel applications and emerging battery technologies, Indonesia's resource base provides significant leverage in global supply chains.

However, rapid capacity expansion has raised serious sustainability concerns. A senior government official warned in October 2024 that at current development rates, Indonesia's nickel reserves could face depletion within 4-5 years if all planned smelters become operational. This stark projection highlights the fundamental tension between aggressive industrial development and long-term resource stewardship.

Export Ban to Industrialization: Indonesia's Policy Arc

Indonesia's journey toward nickel industrialization began with the Mineral and Coal Law of 2009, which prioritized transforming mineral resources into value-added activities. The most decisive action came in 2020 when Indonesia implemented a complete ban on unprocessed nickel ore exports, forcing miners to process materials domestically or cease operations entirely.

This policy represents a calculated economic gamble with far-reaching implications. While the export ban initially reduced Indonesia's raw nickel export revenues, it created powerful incentives for investment in domestic processing facilities. President Joko Widodo demonstrated unwavering commitment to this approach despite international pressure, stating: "It looks like we will lose at the WTO [in a dispute with the European Union], but it's fine, the industry is already built." This confidence reveals the administration's belief that short-term trade dispute costs were justified by long-term industrial development benefits.

The policy's impact has been transformative. Export volumes of nickel and its products increased dramatically from 91.5 tons in 2019 to 775.6 tons in 2022, with values skyrocketing accordingly. This reflects successful channeling of raw materials into domestic processing operations, with export values rising to $20.9 billion in 2021 compared to just $1 billion seven years earlier—a twenty-fold increase demonstrating the potential economic benefits of value-added processing.

Beyond basic processing, Indonesia's ambitions extend up the value chain from producing grade 2 nickel derivatives for stainless steel to grade 1 nickel products for electric vehicle batteries. This progression toward higher-value products represents the next frontier in Indonesia's industrial policy, providing clearer linkages to global battery supply chains and potentially greater economic returns.

Nevertheless, implementation challenges persist. Concerns about rapid resource depletion have prompted calls for more strategic management. Julian Ambassadur Shiddiq, Director of Mineral and Coal Program Development at the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, suggests that Indonesia needs to "regulate its downstream industry that will not only focus on extractive industry, but also on developing its derivative industry."

The depletion narrative faces some contestation. The Indonesian Nickel Miners Association (APNI) maintains that "the lifespan of Indonesia's nickel reserves remains extensive," noting that only 7,000 kilometers of the 15,000 kilometers of potential nickel-rich areas have been explored. This suggests that with adequate exploration investment, nickel reserves could last significantly longer than current projections indicate, though this requires sustained investment in geological surveys and exploration activities.

China's Strategic Presence in Nickel Industrial Parks

China's dominance in Indonesia's nickel industry represents perhaps the most significant aspect of the downstream strategy. Over the past decade, China has invested over $65 billion in Indonesia's nickel industry, fundamentally reshaping the sector and creating complex economic interdependence between the two nations.

The flagship example of Sino-Indonesian cooperation is the Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) in Central Sulawesi, described as both "the largest nickel processing site in Indonesia" and "the world's epicenter for nickel production." IMIP exemplifies the massive scale of Chinese involvement, covering 3,000 hectares and featuring its own seaport, airport, and 2 GW coal power plant. By October 2022, 18 companies operated at IMIP with total investments of $15.3 billion.

The industrial park follows a familiar Chinese development model. As one analysis notes: "The industrial park bears the imprint of a typical export growth-oriented Special Economic Zone from China. Built in a pristine yet resource-rich area in Central Sulawesi, it brought development in the form of new infrastructure like ports, roads, and airports, which connected this once dormant part of the country to other parts of Indonesia and onward to the rest of the world." This approach has effectively integrated previously isolated regions into global supply chains.

Chinese expansion continues unabated. CNGR, a major Chinese nickel processor and Tesla supplier, plans to invest 168.2 trillion rupiah ($10.5 billion) over the next 20 years, adding to its existing $32.1 billion investment since 2021. CNGR is developing facilities across multiple regions, including a 5,000-hectare Konasara Green Tech Industrial Zone in North Konawe, Southeast Sulawesi, expected to create 28,000 local jobs.

Two primary factors drove this development pattern. First, China's Belt and Road Initiative provided a strategic framework for elevating Indonesian projects to national priority status. Second, Indonesia's export ban on raw minerals essentially forced Chinese companies to invest in Indonesian smelters to maintain access to nickel sources. This combination of Chinese expansion strategy and Indonesian resource nationalism created powerful investment incentives.

However, this heavy reliance on Chinese investment has generated international concerns. Nine U.S. senators expressed reservations about a potential U.S.-Indonesia Critical Minerals Specific Free Trade Agreement, citing "weak labor protections in Indonesia, Chinese dominance of its mining industry, environmental implications, and lack of community engagement among Chinese and Indonesian workers." These concerns indicate that Indonesia's Chinese-dependent nickel strategy may constrain its ability to diversify international partnerships.

The industry structure has been characterized as an "oligopsony," where Chinese buyers drive and dominate market dynamics. This concentration potentially limits Indonesia's bargaining power and value capture ability despite its resource wealth, raising complex questions about balancing necessary investment and technology access while maintaining economic sovereignty.

The Energy and Carbon Cost of Current Processing

The environmental footprint of Indonesia's nickel industry, particularly its carbon emissions, presents a significant challenge to long-term sustainability. Nickel processing is inherently energy-intensive, and energy sources dramatically affect overall environmental impact.

Globally, nickel mining generated approximately 120 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent emissions in 2019. Carbon intensity varies widely depending on specific processes and energy sources. For class 1 nickel used in lithium-ion batteries, emissions range from approximately 5-22 tonnes of CO₂e per tonne of nickel. However, across all production pathways and purities, estimates range much wider, from 20-80 tonnes CO₂e per tonne of nickel product.

In Indonesia specifically, four major nickel companies—PT Aneka Tambang (Antam), Merdeka Battery Materials (MBMA), Trimegah Bangun Persada (TBP Harita), and PT Vale Indonesia—produced 353,000 tonnes of nickel in 2023 while generating 15 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions. This represents approximately 26% of Indonesia's primary nickel production of 1.36 million tonnes that year.

The emissions intensity varies dramatically between producers based on energy sources:

| Company | GHG Emissions (tCO₂/tNi) | Power Source |

|---|---|---|

| Vale | 29 | Hydropower |

| Others | 57-70 | Mostly coal-fired |

Vale achieved the lowest greenhouse gas emissions at 28.7 tonnes of CO₂ per tonne of nickel through "its three hydropower plants at Sorawako, with a total capacity of 365 megawatts." By contrast, the other three companies primarily relied on coal-fired power, resulting in much higher emissions ranging from 57 to 70 tonnes of CO₂ per tonne of nickel.

This variation demonstrates both the challenge and opportunity for Indonesia's nickel industry. As production expands, emissions will grow proportionally unless cleaner energy sources are deployed. The four major companies aim to more than double production to 1.05 million tonnes by 2028. At current emissions rates, this could generate 39 million tonnes of greenhouse gases annually, equivalent to 5% of Indonesia's total 2023 emissions.

Environmental impact extends beyond carbon emissions to include local air quality, water pollution, and habitat disruption. IMIP "has been linked to significant environmental pollution and disruptions to nearby communities. Reports from workers and advocacy organizations highlight poor working conditions, with documented cases of industrial accidents resulting in injuries and fatalities." These local environmental and social costs must be considered alongside carbon footprint when assessing nickel industrialization's true impact.

As global markets increasingly demand low-carbon materials for electric vehicles and green technologies, Indonesia's heavily coal-powered nickel industry may face market disadvantages unless it transitions to cleaner energy sources. The contrast between Vale's hydropower-based operations and the coal-dependent industry majority highlights both the challenge and potential pathway toward more sustainable production methods.

Local Value-Add vs Foreign Technological Dependency

A central question in evaluating Indonesia's downstream nickel strategy concerns whether it truly creates domestic value or primarily benefits foreign interests. The evidence presents a complex picture with both achievements and significant limitations.

Positively, Indonesia has successfully increased nickel export values. The shift from raw ore to processed products expanded export revenues dramatically, rising to $20.9 billion in 2021 from just $1 billion seven years earlier. This twenty-fold increase demonstrates the potential economic benefits of downstream processing.

The industry has also created substantial employment opportunities. IMIP alone employs approximately 81,000 workers, while CNGR's planned Konasara Green Tech Industrial Zone expects to create an additional 28,000 local jobs. These employment figures represent significant economic opportunities, particularly in previously underdeveloped regions.

However, critical questions remain about benefit distribution and value creation depth. A study by the Center for Economics and Law Studies (CELIOS) challenges the value-added narrative, suggesting that "the nickel industry can generate economic value-added losses of more than $387.10 million (6 trillion rupiah) in 15 years." The study found that while the industry contributes significantly to exports, it also creates economic burdens, especially due to coal power plant dependence with long-term negative community impacts.

CELIOS research indicates environmental degradation results in "a gradual decrease in economic benefits, notably apparent post the 8th year, with negative indicators surfacing by the 9th year." This challenges simplistic claims that processing automatically creates sustainable economic value and suggests comprehensive cost-benefit accounting is necessary.

Technological dependency remains a significant constraint on Indonesia's value capture ability. While the export ban successfully attracted processing facility investment, technology control and high-skilled positions often remain with foreign partners. This dependency limits both current value capture and potential for future indigenous technological development.

Benefit distribution between local communities and industrial interests appears uneven. Communities near nickel projects report mixed experiences, with industrial development bringing infrastructure improvements alongside environmental damage and social disruption. IMIP has been linked to "significant environmental pollution and disruptions to nearby communities," suggesting substantial local costs.

Revenue sharing with local governments requires reform. Research using regulatory impact assessment suggested that "in the short term, the government needs to revise the revenue sharing scheme for local governments and establish a downstream fund management institution." Such reforms could help ensure communities directly affected by nickel operations receive appropriate compensation and benefits.

These challenges highlight the need for more balanced value creation approaches in Indonesia's nickel industry. Addressing technological dependency, environmental impacts, and equitable benefit sharing will be essential if Indonesia is to achieve genuine economic sovereignty rather than simply hosting foreign-controlled extractive operations.

ESG Financing and the Pressure to Clean Up Supply Chains

As global attention to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors intensifies, Indonesia's nickel industry faces growing pressure to improve sustainability practices. This pressure emanates from multiple stakeholders: international buyers seeking low-carbon materials for green technologies, investors applying ESG criteria to funding decisions, and civil society organizations advocating for responsible mining and processing.

Carbon intensity in nickel production has become increasingly important to buyers, particularly in the electric vehicle sector. As industry analysts note, "With increased regulation on nickel emissions and reporting requirements coming into play, industry scrutiny is set to grow at pace with demand." This suggests Indonesia's heavily coal-powered nickel industry may face market disadvantages unless it adopts cleaner production methods.

Financial institutions increasingly incorporate ESG criteria into investment decisions, affecting Indonesia's ability to finance nickel projects. Supply chain risk assessments conducted for automotive OEMs considering Indonesian nickel sourcing illustrate this trend, equipping "clients with necessary insights to make informed deliberations on whether to source Indonesian nickel and how to best manage risks in the process." Such assessments are becoming standard practice among international buyers and financiers.

In response to these pressures, some nickel producers are investing in more sustainable processing technologies. PT Vale Indonesia and China-based GEM Co., Ltd. have embarked on a "$2.1 billion partnership to create a sustainable, net-zero nickel processing facility in Central Sulawesi." The facility will employ High-Pressure Acid Leaching (HPAL) technology, which "reduces waste and energy use, making it a more sustainable choice for Indonesia."

The project includes a "$61 million Research and Development Center, which will drive innovation in HPAL while fostering local talent development." This type of investment in both cleaner technology and local capacity building represents a potential model for more sustainable nickel processing, though its scale remains small compared to the industry's coal-dependent majority.

President Prabowo has praised such projects as milestones in "Indonesia's industrial evolution," suggesting government support for more environmentally responsible approaches. This high-level endorsement may signal growing recognition that environmental sustainability is becoming economically necessary, not just ethically desirable.

The financial implications of ESG performance are becoming increasingly concrete. Companies with better environmental practices, particularly lower carbon emissions, may command premium prices in markets concerned with supply chain sustainability. Vale, with significantly lower emissions due to hydropower use, is potentially better positioned for such markets than its more carbon-intensive competitors.

As Indonesian nickel companies expand production with four major listed companies aiming to more than double output in the next 3-5 years their environmental and social performance will become increasingly important from both reputational and financial perspectives. This creates economic incentives for cleaner production methods that align with broader sustainability goals.

Domestic Capacity Building: Talent, R&D, and Green Innovation

For Indonesia's nickel strategy to deliver sustainable benefits, the country must build domestic capabilities in technology, skilled labor, and research and development. This represents one of the most significant challenges to achieving genuine supply chain sovereignty rather than merely hosting foreign-controlled processing operations.

Currently, Indonesia remains dependent on foreign expertise for much of its nickel processing technology. Chinese companies in particular control key technologies and often bring their own workers for specialized roles. This technological dependency limits the value depth that Indonesia can capture from its resource wealth and constrains its economic sovereignty.

Recognizing this challenge, some projects have begun incorporating domestic capacity building elements. The PT Vale and GEM Co. project includes a substantial Research and Development Center that will "drive innovation in HPAL while fostering local talent development." Such investments in local R&D capacity are essential for reducing technological dependency over time and building indigenous innovation capabilities.

Employment patterns in industrial parks reveal both opportunities and limitations for local capacity building. While IMIP employs approximately 81,000 workers, questions remain about skilled position distribution between Indonesian and foreign workers, and whether meaningful technology transfer is occurring that builds long-term domestic capabilities.

Green innovation represents a particular opportunity for Indonesia to develop distinctive capabilities. As global markets increasingly demand low-carbon materials, Indonesia could position itself as a leader in sustainable nickel production by investing in renewable energy and cleaner processing technologies. This would align economic and environmental goals while potentially creating competitive advantages in premium market segments.

Vale's hydropower use for nickel operations demonstrates cleaner energy potential. With emissions of just 28.7 tonnes of CO₂ per tonne of nickel—less than half the emissions of coal-powered competitors—Vale's operations show that significant emissions reductions are possible with appropriate energy sources. Expanding such approaches across the industry could substantially improve Indonesia's position in markets demanding low-carbon materials.

CNGR's use of Oxygen Enriched Side Blown Furnace (OESBF) technology, "the first of its kind in the world," illustrates how technological innovation can improve both resource efficiency and environmental performance. This technology "allows for the utilization of nickel ore with a wider range of grades, energy efficiency that minimizes carbon emissions, and environmentally friendly waste production that can be utilized by other industries."

For long-term success, Indonesia must systematically build educational and research capabilities related to battery materials, metallurgy, and clean energy. Without such investments in human capital and indigenous innovation capacity, the country risks remaining dependent on foreign technology providers despite its resource wealth, limiting its ability to capture value and achieve genuine supply chain sovereignty.

The Circular Opportunity: Recycling, Reuse, and Beyond

As Indonesia develops its nickel industry, circular economy approaches offer significant opportunities to extend resource lifespans, reduce environmental impacts, and create additional value streams. Rather than viewing nickel waste as a problem, forward-thinking approaches reimagine it as a valuable resource.

Nickel extraction and processing generate various waste types, including slag, tailings, and emissions. According to the Indonesian Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, "nickel mining can produce significant volumes of residual materials, which, if not managed properly, could lead to environmental risks such as soil degradation and water pollution." However, these waste streams can be repurposed productively through innovative approaches.

Nickel-rich tailings can be reprocessed to extract remaining metals, reducing fresh mining needs while recovering additional value. This approach effectively extends the resource base while minimizing environmental impacts from new extraction. Global examples provide proven models: "Countries like Finland and Canada have successfully developed strategies to transform nickel byproducts into valuable resources, offering Indonesia a model for sustainable waste utilization."

Beyond processing waste, Indonesia has significant opportunities in recycling nickel from end-of-life products, particularly batteries. As electric vehicle adoption increases globally, battery recycling will become an increasingly important source of nickel and other critical minerals. Developing local recycling capabilities would reduce Indonesia's dependence on primary extraction while creating additional value-added activities and extending the effective resource base.

The circular opportunity extends to broader material flows within industrial ecosystems. Waste from one process can serve as inputs for another, creating industrial symbiosis relationships that maximize resource efficiency. For instance, slag from nickel smelting can be used in construction materials, creating additional value streams while reducing waste disposal requirements.

Some Indonesian nickel companies are beginning to recognize these opportunities. CNGR's OESBF technology produces "environmentally friendly waste production that can be utilized by other industries," suggesting movement toward more circular approaches. However, realizing the full potential of circular economy principles will require coordinated policy frameworks, technology investments, and new business models.

For Indonesia to fully capture the circular opportunity, supportive regulations and investments in recycling technology will be necessary. As Julian Ambassadur Shiddiq suggested, Indonesia needs to "regulate its downstream industry that will not only focus on extractive industry, but also on developing its derivative industry." Recycling and circular economy approaches should be central to this broader industry development vision.

The circular economy approach aligns economic and environmental goals. By maximizing value extracted from each tonne of nickel ore mined and establishing closed-loop systems, Indonesia can extend its nickel reserves' lifespan while reducing environmental impacts. Given concerns about potential depletion of high-grade nickel reserves, circular approaches may prove essential for long-term sustainability.

Current resource estimates provide context for this opportunity:

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Nickel ore resources | 17.3 billion tons |

| Nickel metal resources | 174.2 million tons |

| Ore reserves | 5 billion tons |

| 2023 production | 175 million tons |

Conclusion: Resource Nationalism or Sustainable Sovereignty?

Indonesia's downstream nickel strategy represents one of the most ambitious resource nationalization efforts globally. After examining its multiple dimensions, we can assess whether this approach delivers genuine supply chain sovereignty or risks becoming a resource trap with significant environmental and social costs.

The evidence presents a nuanced picture with both promising developments and substantial challenges. Indonesia has successfully transformed from a raw ore exporter to a processor of nickel products, dramatically increasing export values from $1 billion to $20.9 billion in just seven years. The country has attracted massive investment in processing facilities and created tens of thousands of jobs, particularly in previously underdeveloped regions. Some companies are beginning to adopt more sustainable technologies and invest in local R&D capacity.

However, critical challenges threaten the long-term sustainability and value of this strategy. The industry's heavy reliance on coal power creates a substantial carbon footprint that may become increasingly problematic as markets demand greener materials. Chinese companies dominate the industry, controlling key technologies and often capturing the highest-value portions of the supply chain. Environmental degradation and community disruption have accompanied industrial development in many areas. Serious questions persist about the true economic value created once environmental and social costs are fully accounted for.

The future trajectory of Indonesia's nickel industry will depend on how it addresses several key challenges:

Environmental sustainability: Can Indonesia transition its nickel industry toward renewable energy sources and more environmentally responsible practices? Vale's hydropower-based operations demonstrate the potential for cleaner production, but most of the industry remains heavily dependent on coal power.

Technological sovereignty: Will Indonesia develop indigenous technological capabilities and control higher-value segments of the supply chain, or remain primarily a host for foreign-owned processing facilities? Current R&D investments represent initial steps but remain limited in scale compared to the overall industry.

Benefit distribution: Can the economic benefits of nickel processing be more equitably distributed among local communities, workers, and the broader Indonesian population? Reforms to revenue sharing with local governments and stronger labor protections may be necessary to ensure broad-based prosperity.

Resource longevity: How will Indonesia manage its nickel reserves to ensure long-term sustainability? The contrasting assessments of reserve lifespans—from 4-5 years to several decades—highlight the need for careful resource management and increased exploration investment.

Circular approaches: Will Indonesia embrace recycling and circular economy approaches to extend resource lifespans and create additional value streams? Early initiatives show promise but remain limited compared to the scale of the industry.

Indonesia's experience offers important lessons for other resource-rich countries considering similar downstream strategies. Resource nationalism alone does not guarantee economic sovereignty. Without addressing technological dependency, environmental sustainability, and equitable benefit sharing, downstream processing may not deliver the promised national benefits.

For Indonesia to achieve genuine battery supply chain sovereignty rather than falling into a resource trap, it must evolve its strategy beyond simply hosting foreign-owned processing facilities. Developing indigenous technological capabilities, embracing cleaner energy sources, ensuring equitable benefit distribution, and implementing more circular approaches would create a more sustainable and beneficial path forward that truly serves the long-term interests of the Indonesian people.

References

-

Statista. "Indonesia Nickel Reserves." https://www.statista.com/statistics/1480689/indonesia-nickel-reserves/

-

Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. "Indonesia's Nickel Companies Need Renewable Energy Amid Increasing Production." https://ieefa.org/resources/indonesias-nickel-companies-need-renewable-energy-amid-increasing-production

-

Lahadalia, Bahlil, et al. "Downstream Nickel Policy Analysis in Indonesia." Migration Letters. https://migrationletters.com/index.php/ml/article/download/6759/4496/18359

-

Carbon Credits. "Nickel Forecast 2025: Can $66 Billion Investment Solve the Supply Gap?" https://carboncredits.com/nickel-forecast-2025-can-66-billion-investment-solve-the-supply-gap-aemc/

-

Indonesia Business Post. "Indonesia's Nickel Reserves May End in 4 to 5 Years." https://indonesiabusinesspost.com/2939/investment-and-risk/indonesias-nickel-reserves-may-end-in-4-to-5-years

-

Center for World Trade Studies, UGM. "Indonesia's Nickel Industry in the Aftermath of Trade Dispute with the European Union." https://cwts.ugm.ac.id/en/2022/11/03/indonesias-nickel-industry-in-the-aftermath-of-trade-dispute-with-the-european-union/

-

Kompas. "The Long Road of Nickel Value-Added Pursuit." https://www.kompas.id/baca/english/2024/01/14/en-jalan-panjang-perburuan-nilai-tambah-nikel

-

Indonesia Business Post. "APNI Confirms Long Lifespan of Indonesia's Nickel Reserves." https://indonesiabusinesspost.com/2165/Politics/apni-confirms-long-lifespan-of-indonesias-nickel-reserves

-

Global Voices. "How China's Investment in Indonesia's Nickel Industry is Impacting Local Communities." https://globalvoices.org/2025/04/07/how-chinas-investment-in-indonesias-nickel-industry-is-impacting-local-communities/

-

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. "How Indonesia Used Chinese Industrial Investments to Turn Nickel into New Gold." https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/04/11/how-indonesia-used-chinese-industrial-investments-to-turn-nickel-into-new-gold-pub-89500

-

Indonesia Business Post. "A Major Chinese Nickel Processing Company Expands Investment in Indonesia." https://indonesiabusinesspost.com/2720/investment-and-risk/a-major-chinese-nickel-processing-company-expands-investment-in-indonesia

-

Asia Times. "The True Cost of China's Hold on Indonesia's Nickel." https://asiatimes.com/2024/08/the-true-cost-of-chinas-hold-on-indonesias-nickel/

-

CarbonChain. "Understand Your Nickel Emissions." https://www.carbonchain.com/blog/understand-your-nickel-emissions

-

Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. "Rapid Growth Indonesian Nickel Production May Lead Surging Greenhouse Gas Emissions." https://ieefa.org/articles/rapid-growth-indonesian-nickel-production-may-lead-surging-greenhouse-gas-emissions

-

Center for Economics and Law Studies. "Indonesia Nickel Development Analysis." https://celios.co.id/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/EN-CREA_CELIOS-Indonesia-Nickel-Development-compressed.pdf

-

SLR Consulting. "Indonesia Nickel Supply Chain Assessment." https://www.slrconsulting.com/apac/projects/indonesia-nickel-supply-chain/

-

M&M Today. "Indonesia to Host $2.1B Eco-Friendly HPAL Nickel Production Site." https://m-mtoday.com/news/indonesia-to-host-2-1b-eco-friendly-hpal-nickel-production-site/

-

Neo Energy. "How Nickel Waste Can Become Indonesia's Next Big Green Opportunity." https://neoenergy.co.id/how-nickel-waste-can-become-indonesias-next-big-green-opportunity/