Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms and Their Implications for ASEAN Energy Trade

This article analyzes the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), a new policy that imposes a carbon price on imports of carbon-intensive goods to the EU, aiming to prevent carbon leakage and promote global decarbonization. Focusing on the implications for ASEAN countries—which are major exporters of energy and industrial goods to the EU—the article explains how CBAM could impact trade competitiveness, supply chains, and national carbon policies, particularly for sectors like steel, aluminum, cement, and energy exports. It highlights the need for ASEAN nations to enhance their carbon pricing mechanisms, monitoring and reporting systems, and to invest in greener technologies to remain competitive. While CBAM poses risks such as increased costs and administrative burdens, it also presents opportunities for ASEAN to accelerate its green transition and industrial modernization, provided they adapt proactively both domestically and in regional cooperation.

The global effort to combat climate change has entered a new phase, with major economies increasingly looking beyond domestic measures to influence international decarbonization. A pivotal, and somewhat contentious, instrument in this evolving landscape is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Spearheaded by the European Union (EU) as a cornerstone of its ambitious Green Deal and "Fit for 55" package, the CBAM aims to put a price on the carbon emitted during the production of carbon-intensive goods entering the EU. Its stated purpose is twofold: to prevent "carbon leakage"—where EU companies move carbon-intensive production to countries with laxer environmental regulations, or EU products are replaced by more carbon-intensive imports—and to encourage cleaner industrial production in non-EU countries, thereby creating a level playing field for businesses.

For the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a region characterized by dynamic economic growth, significant energy export portfolios, and a diverse range of carbon-intensive industries, the advent of the EU's CBAM presents a complex web of challenges and potential opportunities. Countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand are deeply integrated into global supply chains and have substantial trade relationships with the EU. Their energy sectors, which include significant exports of coal, Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), and palm oil-derived biofuels, alongside growing manufacturing bases for goods like steel and aluminium, are directly and indirectly in the CBAM's line of sight. As the EU tightens its environmental standards, ASEAN economies must navigate the rising influence of EU regulations on global trade flows—particularly concerning fossil fuels, basic industrial materials, and electricity.

This article provides an analytical overview of the EU CBAM, maps ASEAN's energy export landscape, evaluates the potential impacts on the region, and explores strategic responses to adapt to this new reality.

Overview of CBAM Policy Framework

The EU's CBAM is a regulatory instrument designed to equalize the carbon price of imports with that of domestic EU production, which is subject to the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS). It is a key part of the EU's strategy to achieve climate neutrality by 2050.

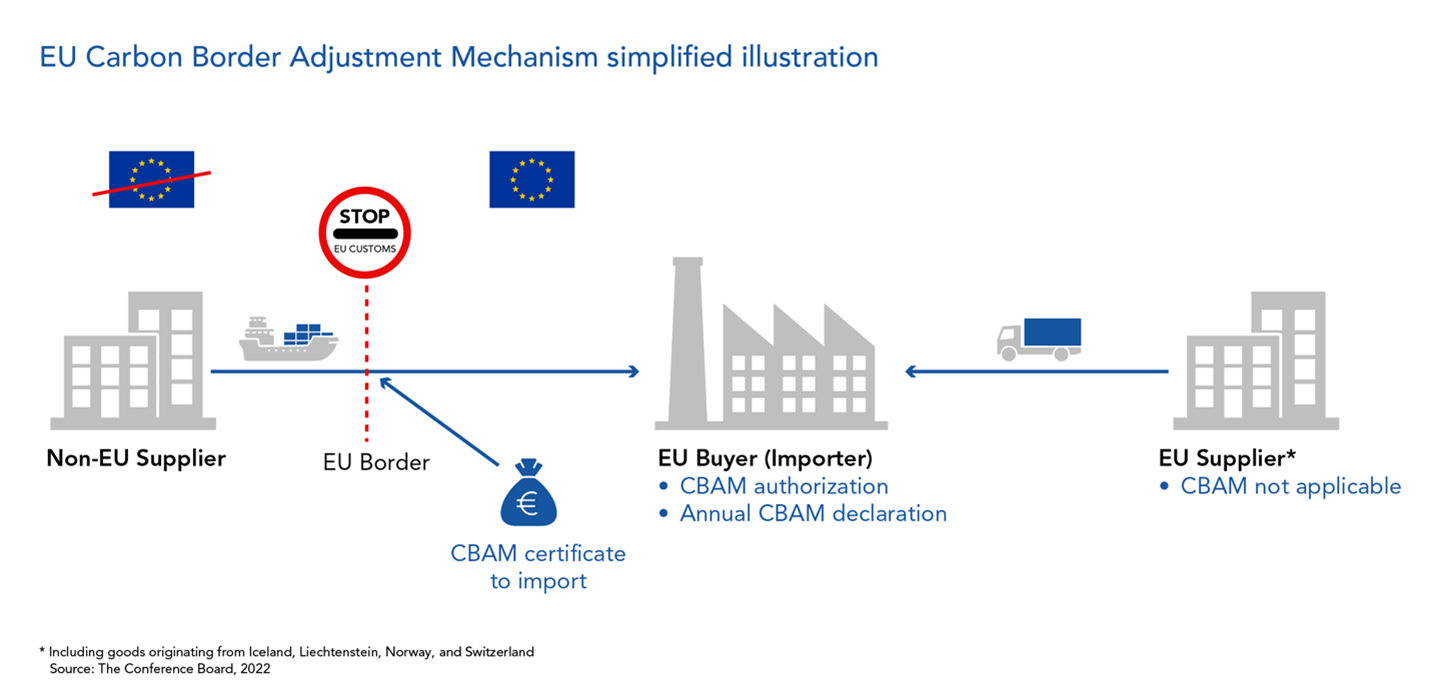

The legal framework for the CBAM was formally adopted in May 2023, with Regulation (EU) 2023/956 establishing the mechanism. It is intrinsically linked to the EU ETS. Under the CBAM, EU importers of covered goods will be required to purchase and surrender "CBAM certificates" corresponding to the embedded greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in those goods. The price of these certificates will be linked to the weekly average auction price of EU ETS allowances. If a non-EU producer can demonstrate that a carbon price has already been paid for the embedded emissions in the country of origin, a corresponding deduction can be made from the CBAM obligation, preventing double pricing.

Covered Sectors

Initially, the CBAM targets sectors deemed to be at high risk of carbon leakage and with significant emissions. These include:

- Cement

- Iron and steel

- Aluminium

- Fertilisers

- Electricity

- Hydrogen

The scope also includes some precursors and a limited number of downstream products, such as screws and bolts made of iron or steel. The European Commission is mandated to assess the potential inclusion of other goods, such as organic chemicals and polymers, by the end of the transitional period, with a view to potentially extending the scope by 2030. This phased approach allows for refinement and gradual adaptation by trading partners.

Phased Implementation Timeline

The CBAM is being implemented in two main phases:

Transitional Phase (October 1, 2023 – December 31, 2025)

- Importers of goods covered by the CBAM are subject to reporting obligations only

- They must submit quarterly "CBAM reports" detailing:

- Volume of imported goods

- Direct and indirect embedded GHG emissions

- Any carbon price effectively paid in the country of origin

- No financial adjustments (purchase of CBAM certificates) are due during this phase

- The first report for Q4 2023 was due by January 31, 2024

Definitive Phase (starting January 1, 2026)

- Importers will be required to declare annually (by May 31st for the preceding year):

- Quantity of CBAM goods imported

- Their embedded GHG emissions

- They will then need to surrender the corresponding number of CBAM certificates

- The phasing-in of financial obligations will be gradual and mirror the phasing-out of free allowances allocated under the EU ETS for the CBAM sectors

- Free allowances for CBAM sectors in the EU are set to be phased out completely by 2034

Reporting Obligations

The reporting obligations during the transitional phase are comprehensive. Importers (or their indirect customs representatives) must report on:

- Total quantity of each type of imported good

- Actual total embedded direct and indirect emissions (CO2e per tonne)

- Any carbon price due in a country of origin for the embedded emissions, including rebates or other forms of compensation

For the first three quarterly reports (Q4 2023, Q1 2024, Q2 2024), companies have the option to report emissions based on:

- The full EU methodology (EU method)

- Equivalent third-country national systems

- Default reference values provided by the Commission

From Q3 2024 (due by end October 2024), only the EU method will be accepted for determining embedded emissions. This underscores the need for ASEAN exporters to rapidly develop robust Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) capabilities aligned with EU standards.

ASEAN's Energy Export Landscape

ASEAN is a diverse region in terms of economic development, energy resources, and carbon intensity. Several member states are significant players in global energy markets, with export profiles that could be affected by the CBAM, either directly (for electricity and hydrogen in the future) or indirectly (through the carbon intensity of manufactured goods).

Major ASEAN Energy Exporters and Traded Energy Types

Indonesia

- One of the world's largest exporters of thermal coal

- Major LNG exporter, supplying markets in Asia and beyond

- World's largest palm oil producer, a key feedstock for biodiesel

- The EU's Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) and its sustainability criteria for biofuels already pose challenges

Malaysia

- Significant global LNG exporter with long-term contracts primarily with North Asian buyers and spot sales to Europe

- Established exporter of crude oil and petroleum products

- Major producer and exporter of palm oil and biofuels, facing similar sustainability scrutiny as Indonesia

Vietnam

- Historically an exporter of crude oil, has seen production decline while imports rise

- Though a coal producer, has become a net importer to fuel its rapidly growing power sector

- Limited cross-border electricity trade, with potential for growth

- Generation mix heavily reliant on coal, which would make electricity exports to CBAM-covered regions carbon-intensive

Thailand

- Produces and imports natural gas, with some exports of petroleum products

- Engages in some cross-border electricity trade with neighbours

- Generation mix includes significant natural gas and coal

Brunei Darussalam

- Heavily reliant on oil and LNG exports, forming the backbone of its economy

Myanmar

- Natural gas exports are a key source of revenue, primarily to Thailand and China

Carbon Intensity of ASEAN's Export Portfolios

The carbon intensity of ASEAN's energy exports varies significantly:

Coal

- Inherently high carbon intensity

- Indonesian coal accounts for over 30% of the nation's exports

- Emissions profile remains among the highest globally per energy unit (IEA, 2023)

LNG

- Cleaner than coal at the point of combustion but still has a substantial carbon footprint

- Methane leakage throughout the value chain (extraction, processing, transport) is a concern

- Energy used in liquefaction adds to embedded emissions

Crude Oil and Petroleum Products

- High carbon intensity associated with both production and combustion

Biofuels

- Complex and contentious carbon intensity

- Potentially lower than fossil fuels on a life-cycle basis

- Emissions from land-use change (e.g., deforestation for palm oil plantations), cultivation, and processing can be substantial

- The EU's stringent sustainability criteria already reflect these concerns

Electricity

- Carbon intensity depends entirely on the generation mix of the exporting country

- ASEAN countries with a high share of coal or unabated natural gas in their power generation would have high-carbon electricity

Hydrogen

- Currently, most production is "grey" hydrogen (from unabated fossil fuels), which is highly carbon-intensive

- Future "green" hydrogen (from renewables) or "blue" hydrogen (from fossil fuels with Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage - CCUS) would have lower embedded emissions

- ASEAN countries are exploring hydrogen potential, but the carbon intensity of production will be key under CBAM

Industrial Exports

- The carbon intensity of ASEAN's industrial exports (steel, aluminium, cement, fertilisers) to the EU will be directly scrutinised under CBAM

- These industries often rely on the domestic energy mix

- If this mix is carbon-intensive, the embedded emissions in these industrial products will be high, triggering CBAM liabilities

Implications of CBAM for ASEAN

The EU CBAM is poised to have multifaceted implications for ASEAN countries, ranging from direct trade impacts on covered sectors to broader pressures on national climate policies and industrial competitiveness.

Direct Impacts on Energy and Industrial Trade

Electricity

- While ASEAN's electricity exports to the EU are currently negligible, future interconnections or dedicated renewable energy export projects could be impacted

- If the exported electricity is generated from sources with high embedded emissions, it would face CBAM levies, making it less competitive

Hydrogen

- As ASEAN nations explore becoming hydrogen producers and exporters, CBAM will be a critical factor

- Exports of "grey" hydrogen to the EU would be subject to CBAM, potentially rendering them unviable

- Creates a strong incentive for ASEAN to focus on green hydrogen or blue hydrogen with high CO2 capture rates

CBAM-Covered Industrial Goods

- Most immediate and significant impact will be on ASEAN exports of cement, iron and steel, aluminium, and fertilisers to the EU

- Countries like Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia export these metals to the EU

- If production processes are more carbon-intensive than EU counterparts, these exports will face additional costs under CBAM

- Could erode their price competitiveness

Energy Exports

- Energy exports per se (e.g., LNG, coal) are not currently included in CBAM

- Secondary sectors may be indirectly impacted

- Future expansions of CBAM's scope could include petrochemicals or refined fuels, heightening risk for ASEAN exporters

Indirect Impacts

- Supply Chain Shifts: EU manufacturers might prefer sourcing intermediate goods from countries with lower carbon footprints or established carbon pricing mechanisms

- Price Impacts: If ASEAN industries pass on CBAM-related costs or the costs of decarbonisation to their domestic customers, this could lead to higher prices for goods within ASEAN

- Upstream/Downstream Effects: Even industries not directly covered by CBAM could be affected if they use CBAM-covered goods as inputs

Risks for ASEAN

- Loss of Competitiveness: The primary risk for ASEAN exports in the EU market if their embedded carbon emissions are high and no (or a low) carbon price has been paid domestically

- Reputational Risks: ASEAN countries not adopting robust domestic carbon pricing mechanisms may be seen as harboring carbon-intensive production

- Investment Leakage: While CBAM aims to prevent carbon leakage from the EU, it could inadvertently cause "investment leakage" from ASEAN

- Administrative Burden: The detailed MRV and reporting requirements of CBAM can be complex and costly, particularly for SMEs

- Stranded Assets Risk: Investments in new carbon-intensive production facilities in ASEAN could become stranded assets more quickly

CBAM as a De Facto Global Carbon Pricing Pressure Point

CBAM is more than just a trade measure; it's a powerful signal and a potential catalyst for global carbon pricing:

- By allowing deductions for carbon prices paid in the country of origin, CBAM directly incentivises trading partners to implement their own carbon pricing mechanisms

- CBAM will effectively establish benchmarks for the carbon intensity of traded goods

- The EU's CBAM might encourage other major economies to adopt similar measures, leading to a "climate club" of nations with comparable carbon pricing and border adjustments

- For ASEAN, this means the CBAM challenge might not be limited to trade with the EU alone in the future

Policy and Legal Considerations

The implementation of CBAM raises significant policy and legal questions for ASEAN countries, particularly concerning the alignment of their domestic climate policies with EU expectations and the compatibility of CBAM with international trade law.

Alignment of ASEAN National Carbon Policies with EU CBAM Expectations

Most ASEAN member states are signatories to the Paris Agreement and have submitted Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). However, the progress in implementing explicit, economy-wide carbon pricing mechanisms that would be recognised under CBAM varies significantly:

Singapore

- Has a carbon tax, currently at S$25/tCO2e (approx. €17)

- Set to rise to S$50-S$80 by 2030

- Represents the most advanced explicit carbon pricing in ASEAN

Indonesia

- Launched a foundational carbon trading system in 2023, initially for coal power plants, with plans to expand

- A carbon tax framework is in place but its broad implementation has been delayed

- Results in a low current effective carbon price

Malaysia

- Developing a domestic ETS

- Has a voluntary carbon market

- No mandatory national carbon tax yet exists

Vietnam

- Planning a pilot ETS from 2025 with full operation by 2028

Thailand

- Implementing a voluntary ETS

- Exploring other carbon pricing instruments

Other ASEAN nations are generally in earlier stages of considering or developing carbon pricing.

Key Misalignments and Challenges

- Price Gap: The current and planned carbon prices in most ASEAN countries are significantly lower than the EU ETS allowance prices (which have fluctuated but often been in the €60-€100/tCO2e range)

- MRV Capabilities: A critical element for CBAM compliance is a robust, transparent, and internationally verifiable MRV system for embedded emissions at the installation level

- Methodological Complexity: The EU's specific methodologies for calculating embedded emissions are complex

- Coverage Misalignment: The sectoral coverage and types of emissions under nascent ASEAN carbon pricing schemes may not perfectly align with CBAM's scope

Opportunities and Strategic Responses for ASEAN

While CBAM presents challenges, it also offers ASEAN countries an impetus to accelerate their green transition, enhance industrial efficiency, and potentially unlock new economic opportunities. A proactive and strategic approach is essential.

Adaptation Strategies for ASEAN Countries

Develop National Carbon Pricing Mechanisms

- Most direct way to retain revenue that would otherwise be paid as CBAM levies to the EU

- Accelerate the design and implementation of carbon taxes or ETS that are robust and cover relevant sectors

- Aim for price levels that gradually align with international benchmarks

- Recycle revenue to support decarbonisation efforts, fund social programs, or enhance industrial competitiveness

Invest in Robust MRV Systems

- Credible MRV at both national and installation levels is non-negotiable for CBAM compliance

- Invest in capacity building, digital MRV infrastructure, and potentially seek international accreditation

Promote Low-Carbon Technologies and Energy Efficiency

- Incentivise investment in renewable energy (solar, wind, geothermal, sustainable biomass)

- Enhance energy efficiency in industrial processes

- Support CCUS where viable

- Research and development in green hydrogen production and other emerging low-carbon technologies

Develop Product Carbon Footprint Certification

- Establish national or regional schemes for certifying the carbon footprint of products

- Align these standards with international norms, including EU requirements

Explore Regional Carbon Market Integration

- A coordinated ASEAN approach to carbon pricing or a regional carbon market could offer economies of scale

- Enhance liquidity and provide a stronger collective voice in international negotiations

- Harmonise MRV standards across ASEAN

Diversify Export Products and Markets

- Explore diversifying export destinations

- Move up the value chain towards less carbon-intensive and higher-value products

Access Green Finance

- Actively seek green finance from international sources (e.g., Green Climate Fund, development banks) and private investors

- Develop national green taxonomies and sustainable finance frameworks to guide investment

Diplomatic and Trade Strategy Approaches

Engage in EU-ASEAN Dialogue

- Continuous dialogue with the EU on CBAM implementation, technical assistance, and recognition of ASEAN's carbon pricing efforts

- Address concerns regarding administrative burden, methodologies for calculating embedded emissions, and potential impacts on ASEAN's development goals

Advocate for Support for Just Transition

- Seek financial and technical support from the EU and other developed countries

- Support for reskilling workforces, developing green infrastructure, and mitigating social impacts

- Explore mechanisms like the EU's Global Gateway initiative for partnerships

Explore Paris Agreement Article 6 Opportunities

- Leverage international transfer of mitigation outcomes (carbon credits)

- Link ASEAN carbon reduction projects with EU compliance needs or other international carbon markets

Develop a Unified ASEAN Position

- Develop a unified or coordinated ASEAN stance on CBAM and related climate-trade issues

- Enhance the region's negotiating leverage

- Ensure that the diverse interests of member states are considered

Participate in International Trade-Climate Discussions

- Actively participate in discussions at the WTO Committee on Trade and Environment and other relevant fora

- Shape the evolving rules and norms around trade-related climate measures

- Collaborate with other like-minded countries to ensure measures are fair, non-discriminatory, and supportive of sustainable development

Conclusion

The EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is undeniably a transformative policy in the global climate and trade arena. It signals a clear intent by a major economic bloc to embed carbon costs into international trade, thereby extending its climate ambitions beyond its borders. For ASEAN energy-exporting and industrial nations, CBAM is not a distant concern but an impending reality that demands immediate attention and strategic preparation.

The mechanism presents clear risks: potential erosion of export competitiveness for carbon-intensive goods, increased administrative burdens, and the challenge of aligning national policies with rapidly evolving international standards. However, to view CBAM solely as a threat would be a missed opportunity. It also serves as a powerful catalyst for ASEAN to accelerate its own journey towards decarbonisation, spur innovation in green technologies, enhance energy efficiency, and ultimately build more resilient and sustainable economies. The pressure to establish credible domestic carbon pricing and robust MRV systems, while challenging, can unlock domestic revenue streams for green investments and drive industrial modernisation.

The coming years, particularly the transition phase leading up to 2026, are critical. ASEAN nations must move beyond a reactive stance to one of proactive engagement and structural preparedness. This involves a multi-pronged approach:

- Domestically: Investing decisively in decarbonisation pathways, establishing effective carbon pricing and MRV systems, and fostering a supportive ecosystem for green industries

- Regionally: Enhancing cooperation on carbon market development, standards harmonisation, and formulating common positions

- Internationally: Engaging constructively with the EU on CBAM implementation, seeking technical and financial support for a just transition, and actively participating in global discussions

CBAM is more than a trade measure; it is a harbinger of an era where emissions transparency and low-carbon credibility are currencies in international commerce. By strategically navigating the complexities of CBAM, the region can not only mitigate the associated risks but also harness the opportunities to foster a new wave of sustainable growth, positioning itself as a responsible and competitive player in a carbon-constrained global economy. The time for ASEAN to act is now.

References

Ambec, S., Esposito, F., & Pacelli, A. (2023). The economics of carbon leakage mitigation policies. TSE Working Papers 23-1408. Toulouse School of Economics (TSE).

AMRO (ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office). (2024). Navigating Carbon Regulations and Green Investment in BRI Partner Countries in ASEAN. Singapore: AMRO.

ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE). (2022). ASEAN Energy Outlook 7. Jakarta: ACE.

ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE). (2025). ASEAN Energy in 2025. Jakarta: ACE.

ASEAN Secretariat. (2024). Climate Change Data Management in ASEAN. ASCC Research & Development Platform on Climate Change, Trend Report No. 7. Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat.

Asia Foundation. (2023). Supporting Carbon Pricing Implementation in Southeast Asia. Kuala Lumpur: The Asia Foundation.

Bux, C., Rana, R. L., Tricase, C., Geatti, P., & Lombardi, M. (2024). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to Tackle Carbon Leakage in the International Fertilizer Trade. Sustainability, 16(23), 10661. MDPI.

Cameron, A., & Baudry, M. (2023). The case for carbon leakage and border adjustments: where do economists stand? Environmental Economics and Policy Studies, 25(3), 435-469.

Centre for Science and Environment (CSE). (2024). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM): The Global South's response to a changing trade regime in the era of climate change. New Delhi: CSE.

Chontanawat, J. (2018). Decomposition analysis of CO2 emission in ASEAN: an extended IPAT model. Energy Procedia, 153, 125-130.

Corporate Leaders Group (CLG). (2023). The European Green Deal, Fit for 55 Policy Package and upcoming milestones. Cambridge: CLG.

Council of the European Union. (2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/956 establishing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Official Journal of the European Union.

Dobranschi, M., et al. (2025). Carbon border adjustment mechanism challenges and implications: The case of Visegrád countries. Energy Reports, X(Y), pp-pp.

European Commission. (2021). Fit for 55: Delivering the EU's 2030 Climate Target on the Way to Climate Neutrality. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2023). EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism -- FAQs. Brussels: Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union.

European Commission. (2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/956 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism. Official Journal of the European Union, L 130/52.

Friawan, D., Aswicahyono, H., Fauri, A., Xu, N., & Febiandita, S. (2023). The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM): Implications for Indonesia. CSIS Working Paper. Jakarta: Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). (2023). Implications of the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) for ASEAN. Policy Brief. Hayama: IGES.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2023). Indonesia Energy Profile: Analysis and Forecasts to 2030. Paris: IEA.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2023). Indonesia 2023 Energy Policy Review. Paris: IEA.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2021). Fiscal Monitor: Fiscal Policy for a Transformed World. Washington, D.C.: IMF.

Kommerskollegium (National Board of Trade Sweden). (n.d.). What the European Green Deal means when exporting to the EU.

Low, P., & Maruyama, M. (2022). Carbon Border Adjustments: WTO Law and Developing Country Responses. Geneva: Graduate Institute.

Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (Indonesia). (2024). Indonesia Coal Production and Export Statistics 2023. Jakarta: Directorate General of Mineral and Coal.

Mungroo, R., et al. (2025). Case Study of Technology Adoption in Carbon Market MRV Systems. UNFCCC.

OECD. (2021). The OECD Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) Proposal: An Overview. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Pramesta, A. D., & Hidayat, S. (2024). Could Renewable Energy Use Boost Goods Export Performance in ASEAN? Economies, Finance and Banking Review, X(Y), pp-pp.

South Centre. (2023). The WTO Compatibility of the EU CBAM: Legal and Policy Considerations for Developing Countries. Geneva: South Centre Policy Brief No. 117.

Springer Nature Communities. (2025, May 9). Impact of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism on the Global South.

Statistics Indonesia (Badan Pusat Statistik). (2024). Statistik Perdagangan Luar Negeri: Ekspor Gas Alam dan Batu Bara 2023. Jakarta: BPS.

Szulecki, K., Fischer, S., & Tosun, J. (2022). The European Union's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: A Climate Club or Global Trade Tension? Climate Policy, 22(1), 112-126.

TESS (Trade & Environment Strategies and Solutions). (2024, August). Making a Border Carbon Adjustment Mechanism Work for Climate, Trade, and Equity. Geneva: TESS.

UNCTAD. (2021). A European Union Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: Implications for developing countries. Geneva: UNCTAD.

World Bank. (2022, July 27). What You Need to Know About the Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) of Carbon Credits.

World Bank. (2023). State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

World Trade Organization (WTO). (2022). Trade and Climate Change. Geneva: WTO.

World Trade Organization (WTO). (2023). WTO Rules and Environmental Measures: Analysis of CBAM-Related Concerns. Geneva: WTO Secretariat.