economics

central bank

Digital RMB’s Global Ambitions: Promise vs Reality in the Emerging Financial Order

By Ang

April 13, 2025

15 min read

This article explores the strategic expansion of China’s Digital RMB and its implications for the global financial order. It contrasts the promise of faster, de-dollarized, and geopolitically autonomous payments with the entrenched dominance of the USD, trust barriers, and technical limitations. Through the case of Indonesia and global data, it offers a nuanced analysis of how emerging economies can navigate the Digital RMB’s opportunities and risks.

The rise of China’s digital renminbi (RMB) officially the e CNY comes at a pivotal moment in the evolution of the global financial system. After decades of U.S. dollar dominance, many emerging economies and geopolitical actors are exploring ways to reduce reliance on the dollar-centric infrastructure. China’s rollout of a central bank digital currency (CBDC) is widely seen as a strategic move aligned with these de-dollarization efforts, promising a new paradigm for cross-border payments and monetary exchange. The digital RMB’s proponents argue it could streamline trade, enhance financial inclusion, and even challenge the U.S. dollar’s supremacy in the long run. Yet critical questions remain about how much of this promise can be realized in practice. Actual adoption of the RMB in global finance remains limited, and significant economic, technological, and trust barriers stand in the way of any rapid upheaval of the existing order. Policymakers, central bankers, and investors must parse the geopolitical strategy behind the digital RMB while weighing the monetary policy implications and risks of a more multipolar currency system.

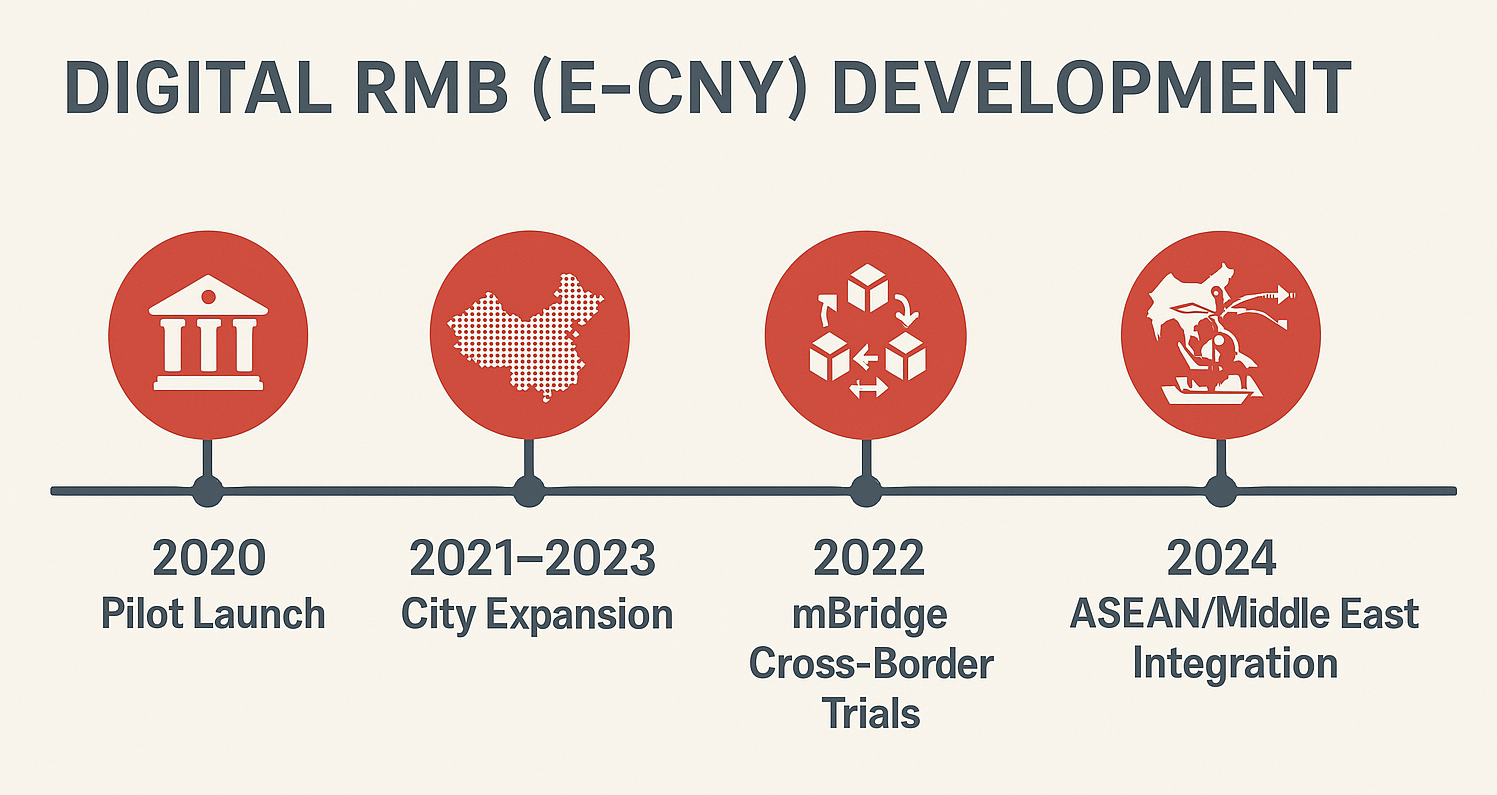

Timeline: Digital RMB Development (2020–2024)

This report provides a comprehensive strategic analysis of the digital RMB’s global ambitions versus the reality on the ground, using a multidisciplinary lens. It frames China’s e-CNY initiative within the broader context of de-dollarization and great-power competition over financial infrastructure. Each section deepens the examination with global macroeconomic data, foreign exchange (FX) market mechanics, digital monetary system trends, and sovereign risk considerations. Section II situates the digital RMB in the context of the existing dollar-dominated system and ongoing shifts. Section III explores the promises of the digital RMB from faster payments to geopolitical leverage drawing on examples and data from credible institutions like the IMF, BIS, SWIFT, PBoC, and World Bank. Section IV provides a case study of Indonesia to illustrate the opportunities and dilemmas faced by emerging economies, comparing Indonesia’s approach with peers such as Thailand, Malaysia, and the UAE. Finally, Sections V and VI outline strategic pathways for engagement with the digital RMB and other CBDCs, emphasizing how countries can harness innovation while maintaining monetary sovereignty, mitigating currency mismatch risks, and navigating a world of potentially competing monetary blocs.

De-Dollarization and the Geopolitical Context

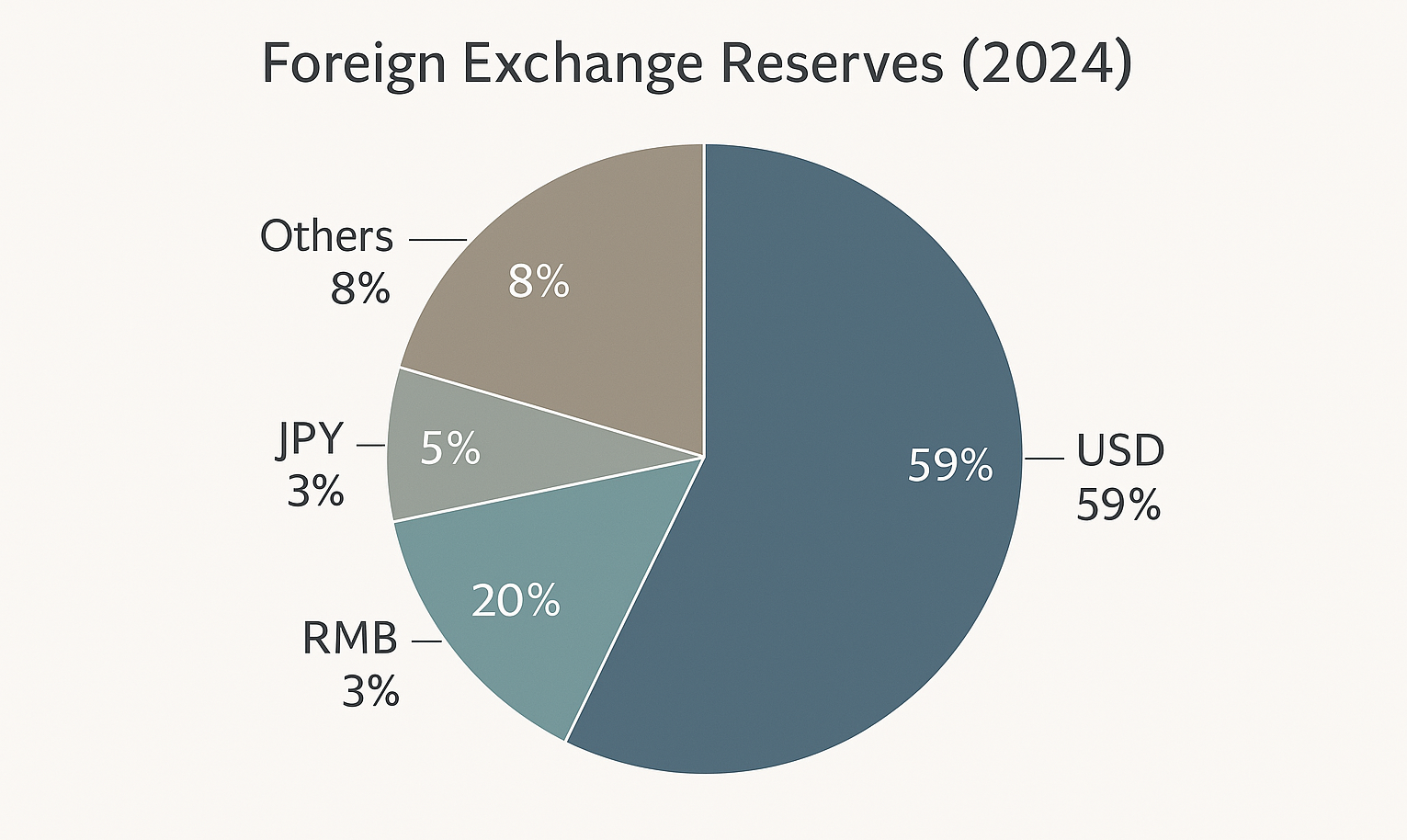

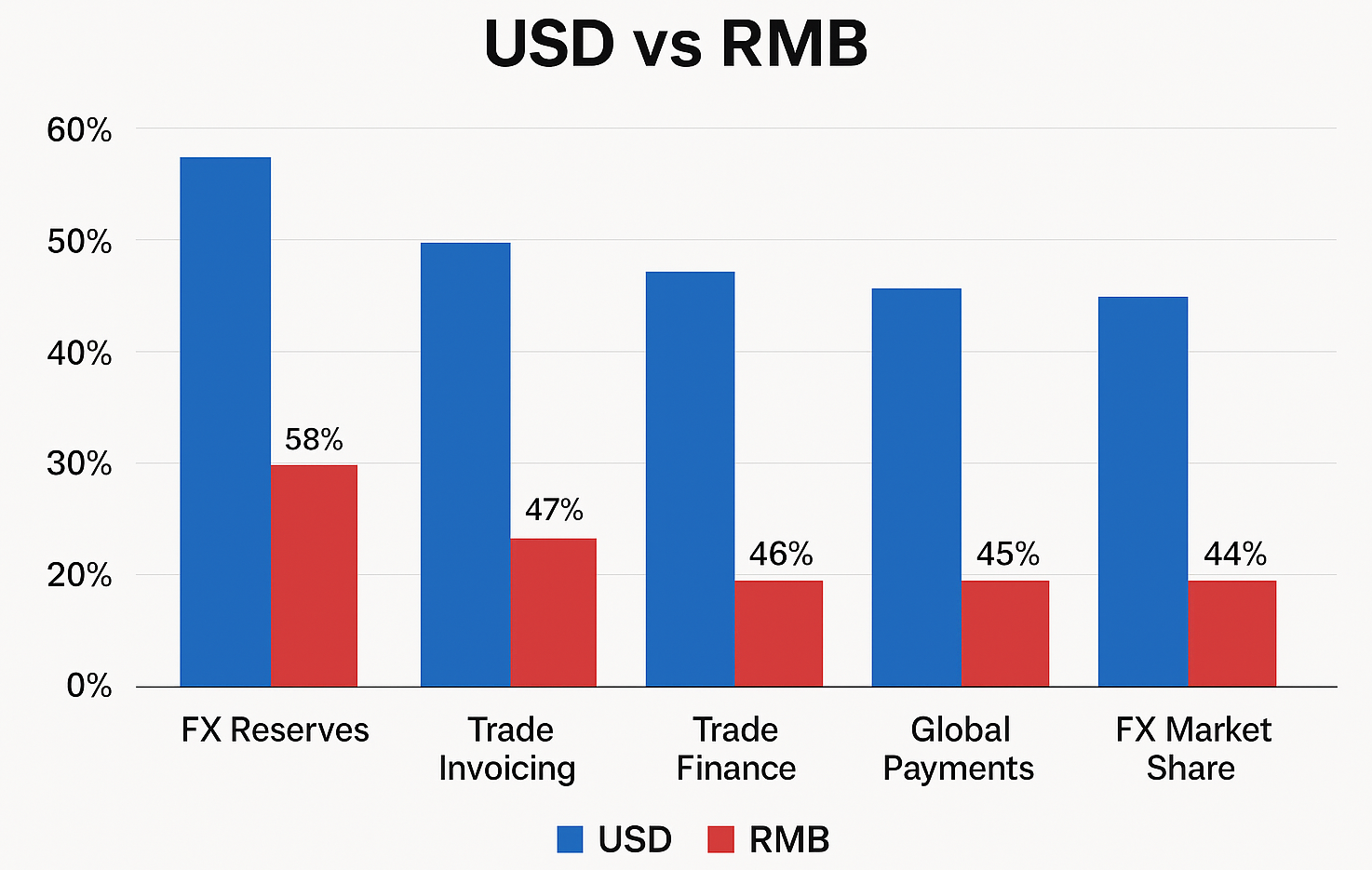

Global foreign exchange reserve composition (2024): USD maintains dominance, while RMB still accounts for only 2–3%, based on IMF data

The digital RMB has arrived against a backdrop of intensifying de-dollarization discourse and geopolitical competition over financial plumbing. The U.S. dollar today remains the world’s dominant currency by virtually every metric about 59% of global foreign exchange reserves are held in dollar assets, 64% of all international debt is dollar-denominated, and the dollar is involved in an overwhelming 88% of global FX transactions. Over half of global trade is invoiced in dollars (54% as of 2022), and the dollar accounts for ~58% of international payment flows outside the Eurozone. This dollar centric system, underpinned by networks like the SWIFT messaging system and U.S. correspondent banks, grants the United States outsized influence from the ability to enforce financial sanctions, to the transmission of U.S. monetary policy globally. However, recent geopolitical rifts and financial shocks have strengthened the resolve of other nations to reduce dependence on the dollar.

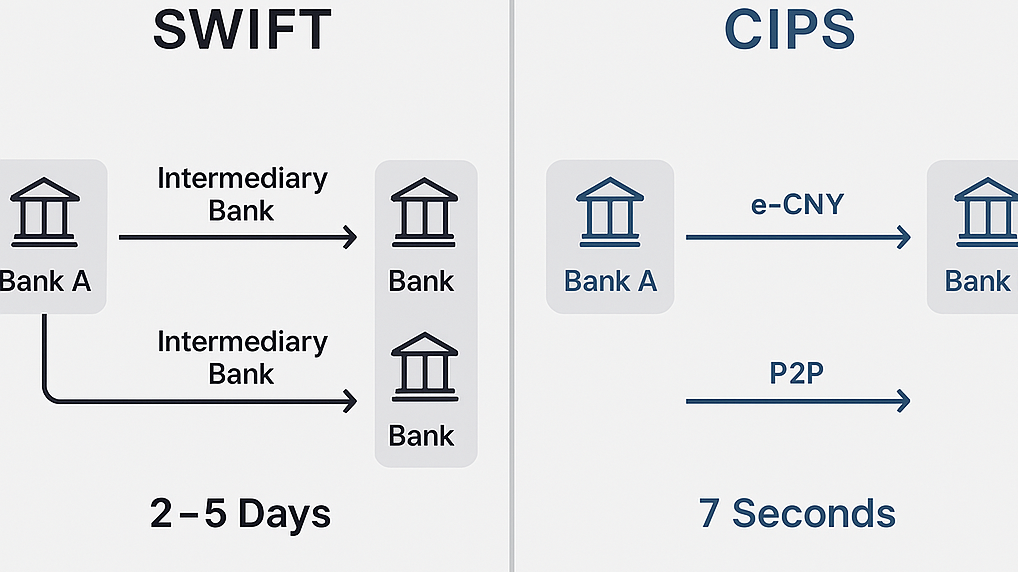

Several factors have converged to drive de-dollarization efforts. For one, geopolitical fragmentation has led countries like Russia, Iran, and China to seek alternatives after experiencing (or fearing) exclusion from the dollar-based system. U.S. sanctions on Russia in 2022, for example, froze a large portion of Russia’s dollar and euro reserves, prompting Russia to pivot to the RMB and gold. In the wake of these sanctions, the use of China’s Cross Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) a clearing network for RMB accelerated (though notably, about 80% of CIPS transactions still rely on SWIFT’s messaging infrastructure). China has also extended bilateral currency swap lines to over 40 countries, providing RMB liquidity to partners (often emerging markets like Argentina and Pakistan that struggle to access dollars). These swaps reflect China’s ambition to internationalize the RMB, but uptake has been modest outside of crisis situations. Indeed, as of late 2023 the RMB comprised only 2–3% of global FX reserves a niche status comparable to the Australian or Canadian dollar and far below the dollar or euro. Even large holders of RMB, such as Russia, have not yet shifted the needle enough to materially dent the dollar’s primacy in reserves.

Comparison of traditional SWIFT messaging system with China's CIPS platform: slower, multi-bank chain vs direct settlement flow using RMB

At the same time, many emerging economies in Asia, Africa and Latin America are exploring local currency arrangements to reduce dollar exposure in trade. Within Southeast Asia, over 80–90% of cross border trade has traditionally been invoiced in USD, which exposes local businesses to dollar exchange rate swings and U.S. monetary tightening cycles. In response, the ASEAN economies have initiated local currency settlement frameworks. For instance, Indonesia concerned that the rupiah’s stability is undermined by excessive USD use in trade has implemented bilateral local currency settlement (LCS) agreements with neighbors including Malaysia, Thailand, Japan, and China. Under these LCS deals, importers and exporters can invoice and settle trade directly in each other’s currencies (rupiah and yuan, baht and rupiah, etc.), bypassing the intermediary step of converting to dollars. Such regional mechanisms are meant to improve efficiency (avoiding double conversions) and dilute the dollar’s dominance, thereby insulating economies from U.S. centric shocks. In 2023, Indonesia went a step further by launching a national “De-dollarization Task Force” aimed at adjusting regulations to encourage use of local and regional currencies for trade and investment. Other emerging nations from India to Brazil have likewise voiced support for conducting more trade in non dollar currencies.

It is within this geopolitical and macroeconomic climate that China’s digital RMB must be understood. Beijing sees an opening to advance the international use of its currency by leveraging new financial technology. The digital RMB (e-CNY) is not just a domestic payment innovation, but a component of China’s broader strategy to challenge U.S. influence in global finance. By building an alternative digital payments ecosystem linking China with trading partners, China aims to reduce the world’s reliance on Western-controlled networks like SWIFT and create new financial pathways that sidestep traditional dollar channels. This ambition has been described as part of a “Digital Silk Road,” complementing the physical Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with a financial infrastructure backbone. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has framed the e-CNY project in part as a contribution to improving cross border payments, a goal also prioritized by the G20. Indeed, China, along with allies, has been active in global forums discussing CBDC standards and interoperability – often emphasizing the need for more inclusive systems that are not dominated by any single country. Implicitly, the digital RMB serves as a geopolitical tool: a successful international e-CNY could bolster RMB usage in trade and finance, thereby weakening one pillar of U.S. strategic power (the ubiquity of the dollar) and giving China and its partners greater autonomy over transactions and liquidity.

However, the pursuit of a multipolar currency order faces significant hurdles. The dollar’s dominance is deeply entrenched, supported by the United States’ economic size, open financial markets, and the network effects of widespread use. Competing with that head-on requires not only technology, but also trust and stability on par with the dollar – factors which we will examine in later sections. Nonetheless, the stage is set for a contest over who will shape the future of money. In this context, the digital RMB stands out as the most audacious attempt to redefine global financial rails in decades, aligning technological innovation with geopolitical intent. The next sections delve into the promises China’s e-CNY holds, and the reality of its progress so far, with an eye toward what this means for the emerging financial order.

The Promise of the Digital RMB

China’s digital RMB initiative comes with a bold promise: to revolutionize cross-border payments and recalibrate the global financial order in favor of greater multi-currency balance. Proponents argue that the e-CNY’s technological design and China’s strategic rollout can address many pain points of the current system while advancing China’s economic statecraft. Three broad categories encapsulate the promise efficiency gains, financial inclusion & development benefits, and geopolitical & monetary leverage. Each is examined below, with data and examples illustrating the potential impact.

Flowchart comparing traditional SWIFT-based cross-border payments with blockchain-powered e-CNY transactions, emphasizing speed and reduced intermediaries

- New Standard in Payment Efficiency

One of the clearest advantages touted for CBDCs like the digital RMB is the dramatic improvement in cross-border transaction efficiency. Today’s international payments often slog through a chain of correspondent banks, incurring multiple fees and delays of 2–5 business days for settlement. China’s e-CNY infrastructure, especially when linked through multi-CBDC platforms, promises near-instant settlement at minimal cost. Pilot tests have delivered impressive results: in a 2022 PBoC pilot between Hong Kong and the UAE, a cross border payment using digital RMB settled in only 7 seconds, bypassing six intermediary banks and cutting transaction fees by 98%. Funds moved via a distributed ledger directly from payer to payee, demonstrating the power of blockchain based clearing to streamline what traditionally is a cumbersome process. In another trial under the mBridge project (a multi-central bank CBDC collaboration), an Indonesian and Chinese joint venture project (“Two Countries, Two Parks”) saw an Industrial Bank of China payment to Indonesia clear in 8 seconds, roughly 100 times faster than the norm. Middle Eastern energy firms testing the mBridge network likewise reported cross-border settlement costs dropping by 75% using the digital RMB and other CBDCs. These examples highlight how a well-designed CBDC network could render the existing SWIFT based system comparatively obsolete a point not lost on observers who call these trials a glimpse of a “Bretton Woods 2.0” financial architecture.

mBridge pilot: 164 transactions across China, HK, UAE, and Thailand with 7–8 second settlement time and 98% cost reduction

The efficiency gains are not just about speed. By enabling direct peer to peer transactions between banks (or even end users) across borders, digital currencies reduce the need for banks to hold nostro accounts in foreign currencies. A Bank for International Settlements (BIS) analysis notes that commercial banks could free up significant capital currently locked in overseas correspondent balances if cross-border CBDC arrangements become widespread. Lower liquidity requirements and real-time settlement also diminish settlement risk. Furthermore, the e-CNY’s system is built with programmability and compliance features for example, transactions are traceable and can have smart contract rules attached to automatically enforce anti money laundering (AML) checks or transaction limits. This means higher security and trust in the payment process. Chinese officials claim that these features make fraud more difficult and oversight easier, potentially appealing to regulators in emerging markets who struggle with illicit flows. If the digital RMB (and associated multi CBDC platforms) can indeed deliver faster, cheaper, and safer cross-border payments at scale, many countries and businesses will have a strong incentive to adopt or at least accommodate this new channel.

- Financial Inclusion and Development Dividend

Beyond efficiency, the digital RMB could foster greater financial inclusion and development, particularly for emerging economies and smaller businesses that are ill-served by the current system. Under the dollar centric model, access to international finance often requires integration into networks dominated by large Western banks and adherence to U.S. defined norms. This can be exclusionary. For instance, small exporters in Southeast Asia or Africa face high costs for trade finance and currency conversion, which eat into margins and deter participation in global trade. A Chinese-led digital payments network offers an alternative pathway. Because the e-CNY can be transacted via mobile wallets and potentially without needing a traditional bank intermediary, it could allow SMEs and unbanked populations to connect directly to international markets through a more open technological platform.

Integration of the digital RMB into Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure projects, such as the Jakarta–Bandung High-Speed Rail

China has actively promoted the digital RMB as a tool for South-South economic engagement. As part of its Belt and Road projects, China envisions integrating the e-CNY into trade and investment flows with partner countries. For example, in projects like the China-Laos Railway and Indonesia’s Jakarta–Bandung High-Speed Rail (both BRI ventures), Chinese companies and contractors could use digital RMB to pay local suppliers and workers, facilitating commerce in remote areas where dollar liquidity is scarce. The PBoC has reported rapid growth in cross border RMB transactions with developing Asia: in 2024, RMB cross border settlements with ASEAN nations reached 5.8 trillion yuan (~$900 billion), a 120% increase from 2021. This surge partly reflects the expanded use of RMB for trade, and digital RMB pilots could amplify that trend by making RMB usage even more convenient for partners. There is also a financial stability angle: countries that rely heavily on USD for trade are vulnerable to USD funding crunches and U.S. interest rate changes. By diversifying into RMB and using digital avenues, they can reduce currency mismatch and possibly secure more stable financing from China. A BIS report even remarked that China, through such initiatives, is “defining the rules of the game in the era of digital currency,” as numerous emerging market central banks join tests to explore these new channels.

Additionally, the digital RMB could help democratize the reserve currency space. Today, holding foreign exchange reserves in USD or EUR usually means investing in U.S. Treasury or European bonds, which smaller countries may find diplomatically and financially constraining. China’s e-CNY, if made accessible offshore, could allow central banks to hold and use RMB liquidity for interventions or emergency support more easily (for example, via a digital wallet held with the PBoC). Already, at least six ASEAN central banks including Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand have added RMB assets to their reserves in modest amounts. A digital version of RMB could further ease such diversification by improving liquidity and reducing transaction costs for RMB assets. The IMF and World Bank have cautiously welcomed the innovation of CBDCs for their potential development benefits, noting that new digital rails could lower remittance costs and boost financial inclusion if implemented with proper safeguards. From a multilateral perspective, a more diverse currency ecosystem is seen as positive for global financial stability, as it spreads risk and reduces over-concentration. In this light, the digital RMB can be pitched not as a disruptive threat, but as a contributor to a more resilient and inclusive international monetary system.

- Geopolitical and Monetary Strategy

It is in the geopolitical realm that the digital RMB’s promise is perhaps most keenly watched. For China, launching the first major power CBDC and pushing it internationally is a chance to seize the initiative in global financial standards. Beijing is well aware that technological standard setting can confer lasting influence (as seen in telecommunications or AI governance), and money is no exception. By pioneering the model for a sovereign digital currency used beyond its borders, China could shape protocols and norms in a way that aligns with its interests and those of the Global South. For example, China can embed its preferences on issues like data sharing, privacy (or the lack thereof), and exchange rate arrangements into the architecture of e-CNY networks. If enough countries adopt compatible systems (e.g. connecting their payment systems to the PBoC’s infrastructure or joining multi CBDC platforms led by China), a China-centric financial zone could emerge, operating partly outside U.S. oversight. Such a zone would grant participants more leeway to transact with one another even if Western sanctions or restrictions are in place. Indeed, countries like Iran and Russia both facing U.S. financial sanctions have strong motivation to use China’s alternative network to conduct trade that’s sanction-proof. The digital RMB offers them an avenue to do so with greater confidence in the reliability of settlement, since transactions could be cleared in central bank money (RMB liabilities at PBoC) without touching the dollar system. This has national security implications: it reduces the threat of being “cut off” from the global economy, a fear that looms large for many nations after witnessing cases like the SWIFT ban on Russia.

China's expanding network of RMB clearing banks across the globe: Frankfurt, Johannesburg, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, and more

From China’s perspective, internationalizing the RMB through digital means also serves a monetary policy goal: increasing the global use of RMB could, over time, lessen China’s own dependence on the dollar for trade and investment. It could also allow the Chinese economy to be more insulated from U.S. Federal Reserve policy. For instance, if more of China’s trade with commodity suppliers is invoiced in RMB (or e-CNY), a U.S. interest rate hike might have a more muted effect on those trade prices and financing costs. Already, we see movement in this direction. By early 2023, roughly 25–30% of China’s own trade (imports and exports) was being settled in RMB, up from low teens just a few years prior. This shift has been especially pronounced in trade with certain partners: China and Brazil signed an agreement in 2023 to conduct bilateral trade in RMB and Brazilian reais, bypassing dollars. Oil trade is another focal point in 2023, China reportedly facilitated the first RMB denominated oil trade with a Middle Eastern country (widely noted that Thailand conducted its first oil purchase settled in digital yuan). If key commodities begin pricing in RMB, it would mark a significant challenge to the petrodollar system. The digital RMB could accelerate such trends by making RMB transactions more convenient and secure for commodity exporters. The People’s Bank of China is actively pushing for e-CNY usage in scenarios like these, showcasing it at trade fairs and in BRI forums as the future of cross border settlement.

China’s e-CNY strategy also promises to bring many countries into its orbit via collaborative pilots and platforms. The PBoC, together with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Bank of Thailand, and Central Bank of UAE, has led the mBridge project under BIS auspices, explicitly aiming to create a multi-currency CBDC corridor for Asia and the Middle East. As of late 2023, 23 central banks from around the world (including the IMF and World Bank as observers) were involved in mBridge experimentation and sandbox tests. By engaging dozens of central banks in learning by doing, China is building a coalition or at least a sympathetic network around its approach. Similarly, China has been generous in providing technical assistance on digital payment systems to developing nations (leveraging its experience with Alipay/WeChat Pay and now e-CNY). This tech diplomacy is drawing comparisons to the spread of the Chinese yuan clearing network a decade ago, when Bank of China helped set up RMB clearing banks in dozens of countries to support trade settlement. The result is a growing infrastructure of international RMB use that spans everything from hardwired payment rails to diplomatic agreements. If this promise is realized, the world could see the emergence of a parallel financial system centered on the RMB one where China has a much larger influence on global liquidity and where countries have an alternative to the U.S. led Bretton Woods institutions for their financing needs.

In sum, the promise of the digital RMB is far reaching. It is technologically compelling, potentially delivering quantum leaps in transaction efficiency. It aligns with a genuine demand among many nations for a more diversified and accessible financial system, hinting at development gains. And it is clearly a pillar of China’s grand strategy to reshape the geopolitical financial landscape, reducing Western leverage and increasing its own. Little wonder that a 2021 Economist article referred to China’s digital currency moves as a “financial revolution” and some have speculated about a coming “post-dollar” era if these trends accelerate. However, turning these ambitions into reality is another matter entirely. The next section provides a reality check on the digital RMB’s progress and the structural challenges that may temper its impact.

The Reality: Constraints and Challenges in Global Adoption

For all its promise, the digital RMB faces a sobering reality check. The emerging financial order is unlikely to be upended overnight, and the RMB digital or not has a long way to go before it can rival the dollar on a global scale. As of 2025, the data and behavior of market participants suggest that the RMB’s international footprint remains limited, and significant obstacles could blunt the digital RMB’s trajectory. This section examines key realities: the current usage of RMB in global finance, the technical and trust barriers to wider adoption, and the broader systemic factors that will determine how far the digital RMB can go.

- RMB’s Global Role: Still Marginal Compared to the Dollar

Despite recent growth, the RMB’s share in most categories of international finance is minor an order of magnitude below the dollar’s. According to SWIFT payment data, the RMB accounted for roughly 3–4% of global payments by value at the start of 2024, up from just ~2% a couple years prior. This rise (which saw the RMB overtake the Japanese yen to become the 4th most-used currency in international payments) is notable, but still pales in comparison to the U.S. dollar’s ~47% share and the euro’s ~23%. In global foreign exchange reserves held by central banks a crucial indicator of trust the RMB makes up only about 2–3% of allocated reserves. This is a doubling from its 1% level in 2016, but remains a “niche” status; by contrast the dollar comprises 58% and the euro 20% of reserves. Even Japan’s yen and the UK’s pound each command around 5% or more. The limited appetite for RMB assets is revealing: surveys indicate only a small fraction of central banks plan to significantly increase RMB holdings in the near future.

Comparison of USD and RMB in FX reserves, trade invoicing, trade finance, payment share, and FX turnover

In trade invoicing and financing key arenas the digital RMB aims to transform the dollar’s dominance likewise endures. Outside of trade with China itself, very little global commerce is denominated in RMB. By one estimate, the RMB is used for only ~5% of worldwide trade invoices (the dollar being used for over 50%, even in transactions not involving the U.S.). China has managed to get more of its own trade settled in RMB (about a quarter of Chinese exports and imports now), but foreign firms often quickly convert those RMB back to dollars or other hard currencies, rather than use them broadly. In trade finance, which includes instruments like letters of credit for exporters, the RMB’s share has risen to roughly 6%, now roughly on par with the euro. Yet the U.S. dollar still utterly dominates trade finance with 84% share reflecting that when trust is paramount (as in guaranteeing payment for shipments), banks overwhelmingly prefer the currency with the deepest markets and history of stability (the USD). On the foreign exchange market, the RMB accounts for 7% of turnover (recall, FX shares sum to 200% because two currencies are involved in every trade), lagging well behind the dollar (88% of trades involve USD) and even behind currencies like the British pound and Japanese yen. These statistics paint a clear picture: the international use of RMB, though growing from a low base, is still a fraction of the use of the dollar. Any near-term scenario where the digital RMB dramatically alters these shares would require unprecedented shifts in investor and trader behavior, which historically change only gradually.

- Technical and Network Hurdles

The digital RMB’s technological advantages are real, but implementing them on a global scale faces many practical challenges. First, achieving interoperability between the e-CNY and other countries’ systems is complex. While pilot projects like mBridge proved technical feasibility in controlled environments, scaling up requires linking disparate financial systems, each with their own technology and regulatory standards. The BIS has cautioned that simply interlinking CBDCs is “not easy to implement” and often requires significant coordination and common standards that can be hard to achieve. For widespread adoption, other central banks would need either to join China’s networks or develop compatible ones a process that introduces governance questions (who oversees the network?) and technical ones (how to handle currency conversions, data formats, cybersecurity, etc.). So far, most countries are cautiously experimenting rather than fully committing. There are currently 134 countries at some stage of CBDC exploration, and nearly all G20 nations have pilots or development in progress. However, many are choosing to focus on their own domestic digital currencies or regional initiatives rather than plug into a foreign system wholesale. The European Central Bank, for instance, is working on a digital euro primarily for use inside the Eurozone. The U.S. has not launched a digital dollar (and political opposition makes a retail Fed CBDC unlikely soon), but it is participating in cross border wholesale trials (like Project Agora) in a multilateral setting. This indicates that major economies prefer a multilateral approach (through the BIS or IMF) over simply adopting the e-CNY rails. China’s network, to truly gain global traction, would need to either persuade many countries to adopt its standards or ensure interoperability with whatever multilateral standards emerge a process likely to take years of negotiation.

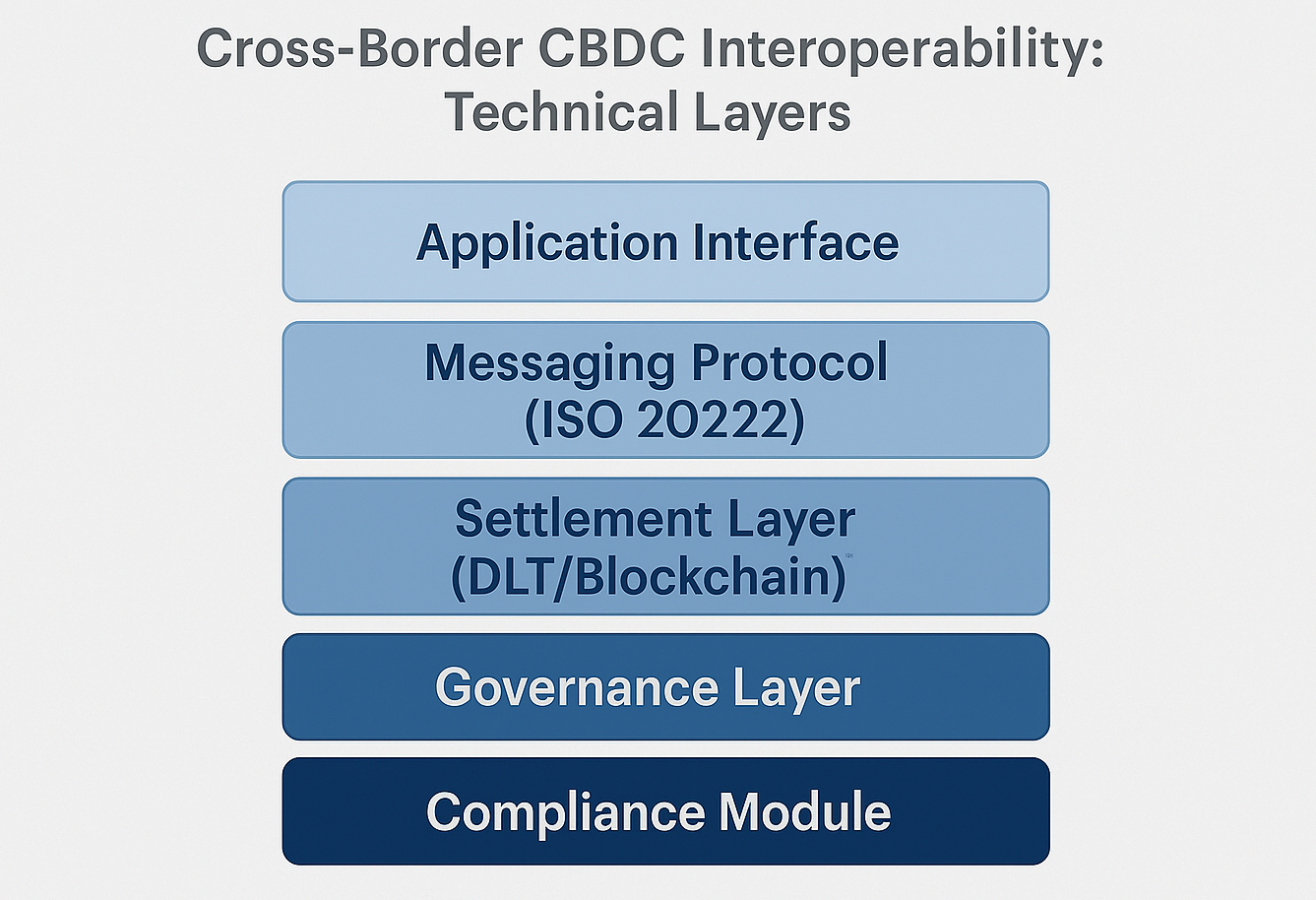

Cross-border CBDC interoperability architecture: application interfaces, messaging protocol (ISO 20022), DLT settlement, governance, and compliance.

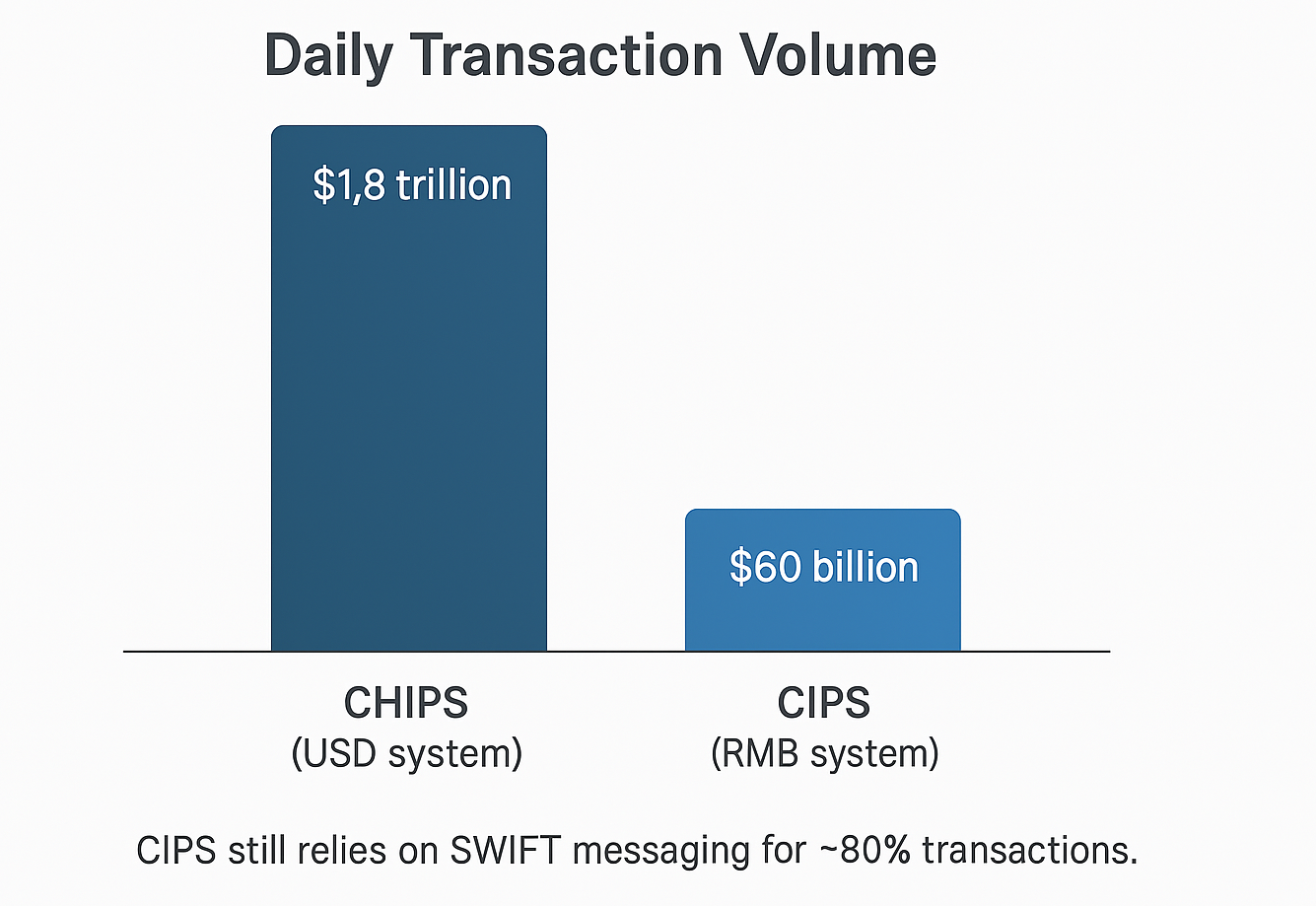

Daily volume comparison: CHIPS ($1.8T USD) vs CIPS ($60B RMB). CIPS still partially reliant on SWIFT messaging.

Another technical hurdle is the question of scalability and reliability. The volumes handled by existing dollar-based systems are immense: for example, CHIPS (the U.S. dollar clearing house) processes about $1.8 trillion in payments per day. By contrast, China’s CIPS processes about $60 billion per day only a few percent of CHIPS volume. Digital RMB trials have so far been limited in scope (the mBridge pilot, for instance, handled $22 million in total across 164 transactions among select banks). It remains untested whether the e-CNY infrastructure can handle large scale global flows without bottlenecks. Issues of cybersecurity and resilience are paramount any outages or hacks on a CBDC network could be catastrophic for confidence. Incumbent systems, while slower, are robust from decades of iteration. Furthermore, if the digital RMB were to see massive international use, the PBoC would need to provide ample RMB liquidity abroad to facilitate conversion and settlement, effectively acting as a global lender or market-maker in RMB. This raises questions: is China willing to allow potentially unlimited outflows of RMB for this purpose, given its traditionally tight capital controls? The PBoC might face a dilemma between promoting international use and maintaining control over its currency and financial system. A true global currency usually requires an open capital account (so foreigners can move in and out freely) and deep bond markets for investment – areas where China still imposes notable restrictions. Unless those structural issues are addressed, many central banks and investors will be reluctant to hold large RMB balances, digital or not, limiting the currency’s ability to expand globally.

- Trust, Governance, and Geopolitical Constraints

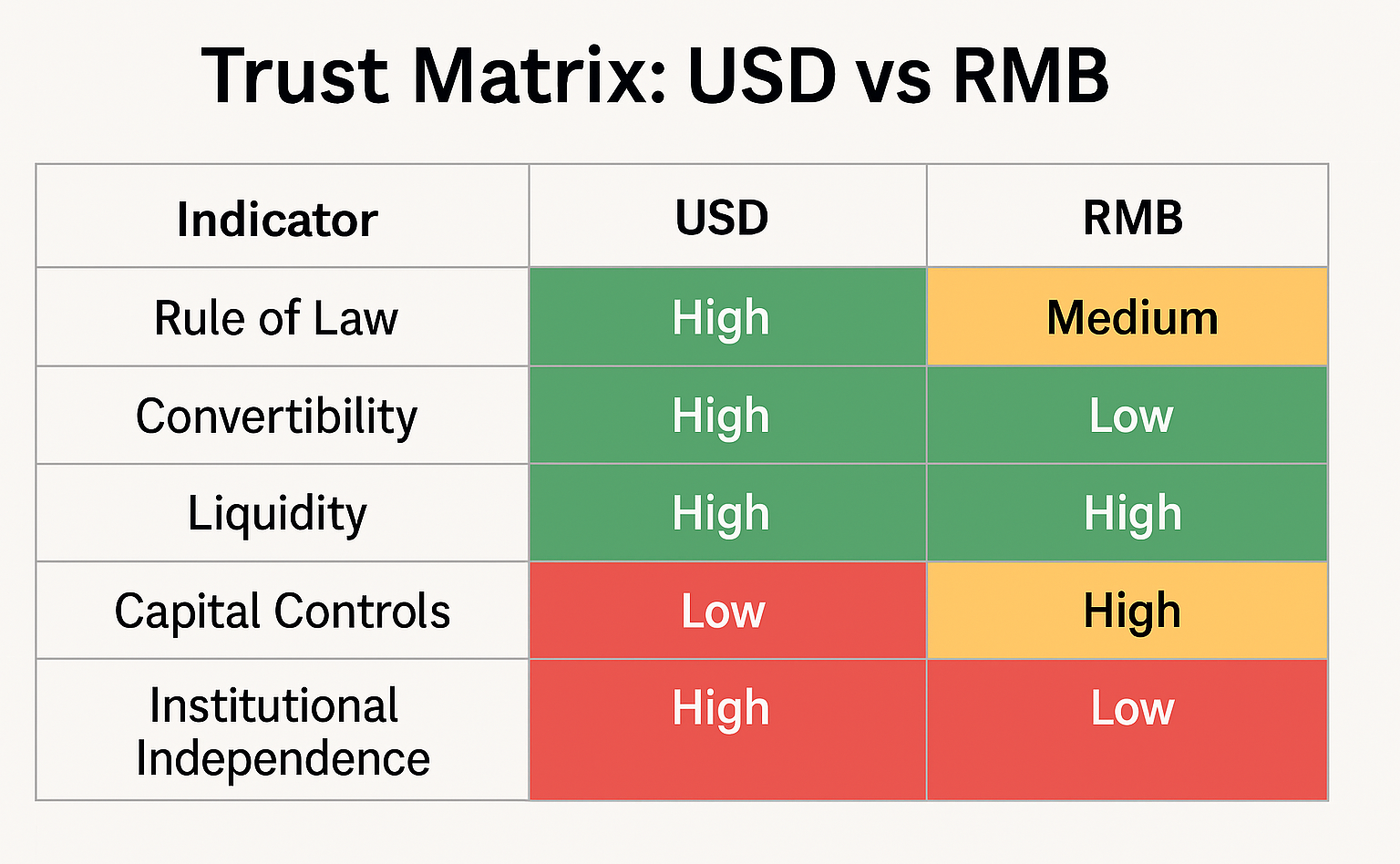

Arguably the biggest challenges are trust and governance. The dominance of the U.S. dollar is not just a product of habit or network effects, but of a relatively high level of trust in U.S. institutions and rule of law. International investors know that the U.S. Federal Reserve is independent and focused on inflation and growth, not on using the dollar as a political weapon (sanctions are a separate tool implemented via banks/government). The U.S. government does not impose capital controls on the dollar, and U.S. Treasury markets are extremely liquid and open. For the RMB, international hesitancy is tied to the fact that the currency is seen as more tightly controlled by the state, less transparent in governance, and subject to geopolitical risk (could China use its currency networks to surveil transactions or exert pressure on countries?). Some analysts in the West have raised concerns that using the digital RMB might enable Chinese authorities to gather data on foreign users’ spending or to cut off transactions in a conflict scenario. Although some of these fears may be exaggerated – indeed, some research notes that technical design could limit data sharing – they highlight a fundamental trust deficit the e-CNY must overcome, especially in markets with deep ties to the U.S. or where public opinion of China is wary. So far, no major economy has indicated it would drop existing systems in favor of the e-CNY. Instead, many are signaling they will proceed prudently: for example, Singapore and the UK are working on their own digital currency experiments and ensuring any cross-border link with China is only one of many links. Even among China’s partners, there is caution. Take the example of swap lines: China has large RMB swap lines with dozens of countries, but during periods of market stress (like the COVID-19 shock of 2020), central banks still turned primarily to the U.S. Federal Reserve’s swap lines for dollar liquidity rather than activate Chinese swap lines. This suggests that in a crunch, the dollar’s safety and ubiquity still trump alternative options. That dynamic likely carries over to the digital realm in a financial crisis or geopolitical showdown, will international investors trust and use the Chinese network, or flock back to dollars as a safe haven? For now, confidence in the RMB under duress is untested.

Trust factors comparison: USD vs RMB on convertibility, rule of law, institutional independence, capital mobility, and transparency.

Governance questions also loom large. If the digital RMB network expands, who controls the rules of this new financial infrastructure? China’s central bank would naturally have outsized influence on any network it built. Other countries may be uncomfortable ceding such influence, recalling how they chafe at U.S.-dominated institutions. The ideal solution might be a multilateral governance structure (perhaps under the BIS or IMF) for any cross border digital currency platform but that dilutes China’s control and is not exactly what Beijing is pursuing with its home-grown system. Additionally, the emergence of competing monetary blocs is a real concern. We could envision a fragmented scenario: a “China led bloc” transacting in e-CNY and connecting to CIPS, and a “West led bloc” transacting in digital dollars/euros and sticking to SWIFT, with some neutral players in between bridging the two. Fragmentation would diminish the efficiency gains (because interoperability is lost) and could force countries to take sides or face higher costs to transact across blocs. This outcome would be economically suboptimal and risky for global stability. The IMF has warned against such fragmentation, advocating instead for common principles and interoperability so that CBDCs improve global payments without creating isolated silos. It remains uncertain whether geopolitical rivalries will allow that collaborative outcome. The U.S. and EU, for instance, may be reluctant to let a Chinese-designed system become a global standard and might push their own standards or require higher compliance burdens on any transactions involving the digital RMB (ostensibly for AML or security reasons).

In short, while the digital RMB is technologically advanced and strategically positioned, real-world adoption faces frictions. Countries and market actors will make pragmatic choices: they might use the e-CNY for certain transactions where it offers clear benefits (e.g. trade with China, or within a pilot program), but they are unlikely to abandon the dollar-based system unless the RMB system proves equally safe, open, and reliable. As of now, the RMB’s global usage remains confined largely to cases involving China itself – unlike the dollar which is used universally. Even many of China’s Belt and Road loans are still denominated in dollars, as borrowers prefer a currency with global acceptance. The digital RMB does not automatically solve the confidence gap. Monetary policy considerations also act as a brake: China cannot internationalize the RMB too quickly without risking loss of control over its domestic money supply and exchange rate. The PBoC’s careful, city by city rollout domestically (the e-CNY was still officially in pilot in 17 regions as of mid-2024) shows a preference for gradualism. Indeed, by mid-2024 the cumulative e-CNY transaction volume was reported at ¥7 trillion ($1 trillion) since launch a substantial sum, but within a controlled environment and still a tiny fraction of China’s total retail payments. International expansion will likely follow the same cautious approach, focusing on specific use cases (like border trade zones, tourism, or interbank transfers under bilateral agreements) rather than a big bang global launch.

The reality, then, is one of incremental change, the digital RMB is chipping away at edges of the dollar system, finding niches where it can thrive (regional trade with willing partners, novel payment corridors, etc.), but it is not (yet) a wholesale replacement for the existing order. The dollar centric system itself is adapting for instance, SWIFT is testing its own solutions for faster payments and even exploring how to carry CBDC messages, aiming to remain relevant. Moreover, other countries’ digital currency projects (India’s, Brazil’s, the ECB’s digital euro) will create multiple digital currencies in play, not just the RMB. We are likely headed into a world of coexistence, where the digital RMB is one important piece of a larger puzzle. The next section uses Indonesia’s experience as a lens to explore how a major emerging economy is navigating this complex reality balancing the allure of the digital RMB’s promise with the imperatives of domestic stability and strategic autonomy.

In case Indonesia’s Perspective: Opportunities and Dilemmas

Indonesia, as Southeast Asia’s largest economy and a key trading partner of China, provides a telling case of how emerging countries are approaching the digital RMB and the shifting monetary landscape. On one hand, Indonesia sees clear opportunities in embracing aspects of the RMB’s rise; on the other, it faces dilemmas in preserving its own monetary sovereignty and balancing great power influences. By examining Indonesia’s stance and comparing it with peers like Thailand, Malaysia, and the UAE, we can appreciate the nuanced decisions policymakers are making in response to China’s digital currency push.

Opportunities for Indonesia in the Digital RMB:

- Reduced Dollar Dependence in Trade: China is Indonesia’s largest trading partner (bilateral trade exceeding $110 billion annually), and traditionally most of that trade is invoiced in U.S. dollars. This means Indonesian importers must obtain USD to pay Chinese exporters, adding costs and exposure to USD/IDR exchange swings. Using RMB directly especially via a digital platform could simplify transactions and cut conversion costs. Indonesia has already taken steps with China to encourage direct RMB/IDR trade settlement (via the LCS agreement in 2021). The digital RMB could turbocharge this by making it even easier for Indonesian firms to acquire RMB digitally and pay Chinese counterparts instantaneously. For Indonesia, settling a larger share of its $50+ billion in imports from China in RMB would reduce the need to tap dollar reserves for those payments, thus easing pressure on its FX reserves and currency. It also aligns with Bank Indonesia’s (BI) goal of de-dollarizing regional trade to stabilize the rupiah. The potential benefit is evidenced by numbers: currently only an estimated 1–4% of Indonesia’s total trade is in yuan/RMB; even a modest increase of that share could improve Indonesia’s resilience to dollar liquidity crunches.

- Efficiency Gains for Businesses: Indonesian businesses could gain from the efficiency of digital currency transactions. For example, an Indonesian commodity exporter shipping coal or palm oil to China could receive payment in e-CNY within seconds of delivery confirmation, rather than waiting days for a dollar wire transfer to clear. Faster receivables mean better cash flow management. Likewise, Indonesian tourists or students in China (and vice versa) could exchange currency digitally at better rates than cash or card networks offer. Some of these benefits are already being tested: in late 2023, media reports noted that in the “Two Countries, Two Parks” industrial zone (a joint Indonesia-China project), digital RMB was successfully used for a cross-border payment. Such pilots signal to Indonesian banks and firms that they should start preparing for a new era of payments. Bank Indonesia has publicly acknowledged that wholesale CBDC (including potentially linking with others) might enable more efficient cross border transactions in the future. Indonesia is thus exploring the digital RMB not in isolation, but as part of a broader fintech innovation drive to make transactions cheaper and faster for its economy.

- Access to Alternative Financing: Indonesia has large infrastructure needs and has borrowed from both Western led institutions and China. The availability of RMB financing via Chinese policy banks has grown under the Belt and Road Initiative. If digital RMB mechanisms make RMB loans or project investments more straightforward, Indonesia could tap into those with potentially fewer strings attached regarding currency risk. For instance, a Chinese bank could disburse a loan for a power plant in digital yuan, which Indonesian contractors could directly use to buy equipment from Chinese suppliers, all on a transparent ledger. This avoids the hassle of converting USD to IDR to RMB, etc. It might also come with lower interest rates if China promotes the use of its currency by offering favorable terms. In essence, the e-CNY could grease the wheels of investment flows from China to Indonesia. Countries like Indonesia see value in having multiple options: if U.S. interest rates spike or Western funding dries up, having a functional RMB channel is a useful hedge. The UAE, for example, has eagerly courted RMB clearing and even raised debt in RMB, as part of diversifying funding sources a model that Indonesia could also consider on a selective basis.

- Strategic Alignment and Influence: Politically, engaging with the digital RMB initiative allows Indonesia to have a say in shaping emerging rules. Indonesia has maintained a non-aligned stance historically, and as such it tends to engage with all major powers. By participating in pilots or dialogues around the e-CNY, Indonesia positions itself as a forward-looking nation in ASEAN that China might view as a partner in expanding the Digital Silk Road. This could potentially yield diplomatic dividends, ensuring Indonesia remains influential in regional fintech standards-setting (possibly through bodies like the ASEAN Financial Innovation Network). Already, peers like Thailand have been active: the Bank of Thailand joined the mBridge collaboration early and completed pilot transactions with e-CNY, including an oil purchase settled in digital RMB. Indonesia would not want to be left behind by neighbors in such a strategically important development. Carefully embracing the digital RMB where it makes sense could strengthen Indonesia’s role as a regional intermediary between the Chinese and Western financial spheres.

Dilemmas and Risks for Indonesia:

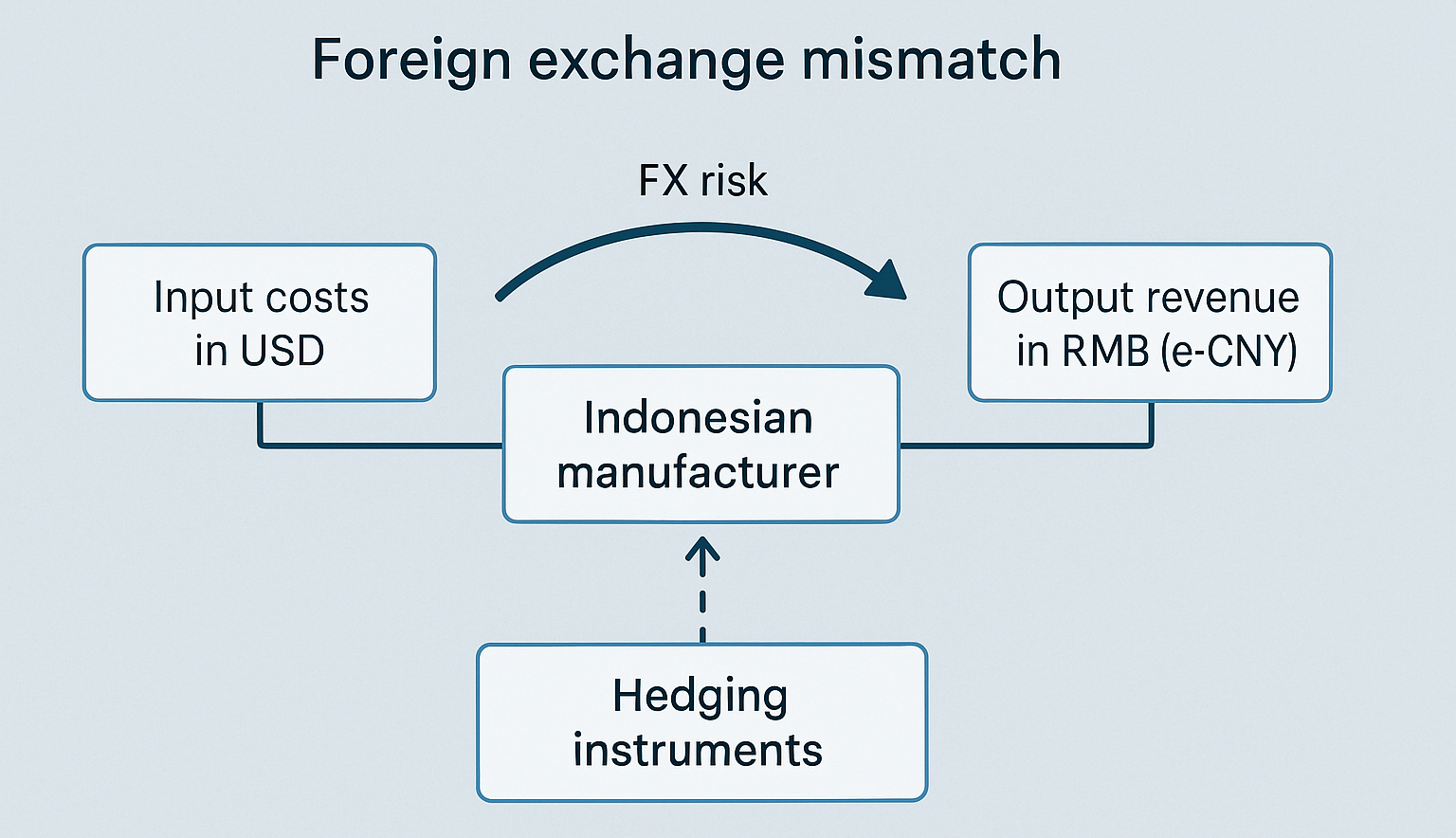

Scenario of exchange rate mismatch for Indonesian firms: costs in USD and revenue in RMB, requiring complex hedging solutions

- Monetary Sovereignty Concerns: Indonesia’s central bank is very protective of the rupiah’s primacy. By law, rupiah is the only legal tender in domestic transactions. Officials have expressed that any foreign digital currency (be it Libra/Diem, digital dollar, or e-CNY) should not undermine Indonesia’s monetary sovereignty. A major concern is “digital dollarization” or in this case, digital yuanization. If Chinese e-CNY wallets became common among Indonesian citizens or firms, it could lead to RMB circulating parallel to the rupiah, weakening BI’s control over money supply and credit conditions. Even though BI would likely ban direct use of e-CNY in retail transactions locally, the line can blur with technology (for instance, an Indonesian could hold a Chinese e-wallet and use it online). Indonesia will thus calibrate its approach: welcoming digital RMB for cross border use (trade, remittances) but not for domestic retail use. This stance is similar to India’s, which has also been cautious about foreign CBDCs in its economy while working on its own digital rupee. Maintaining this balance is tricky too strict, and Indonesia misses out on benefits; too lenient, and rupiah could face competition on its home turf. BI Governor Perry Warjiyo has indicated their future digital rupiah will be designed to be the “only digital legal tender” in country, implying frameworks will ensure other CBDCs are interoperable but not replacing local currency.

- Currency Mismatch and Financial Stability: If Indonesia increases borrowing or trade invoicing in RMB, it must manage currency risk carefully. A key lesson from emerging market crises is to avoid mismatches where debt is in a foreign currency but income is in local currency. While trading in RMB for exports and imports can be balanced (export revenue in RMB can pay for import costs in RMB), problems arise if, say, Indonesian firms take a lot of RMB loans but the domestic economy earns mostly rupiah. A depreciation of the rupiah against RMB would then inflate the burden of those loans. Currently, Indonesia’s foreign debt is largely in USD and JPY; adding RMB debt could diversify but also add a new risk if not hedged. There is also the question of convertibility RMB received by Indonesian firms need to be convertible to rupiah for local use, but China’s capital controls mean RMB outflows are subject to Chinese approval. In a crisis, if China restricted RMB flows (for instance, to stem capital flight), Indonesian entities might find their RMB funds less usable. This is a different dynamic than holding USD, which is freely convertible globally. Thus, while RMB use can reduce dependency on USD, it introduces dependency on the Chinese financial system. Indonesia will have to weigh this in calibrating how far to go. Maintaining a healthy buffer of multiple currencies in reserves (USD, RMB, JPY, gold, etc.) is one mitigation and indeed Indonesia has started to include RMB assets in its reserves mix.

- Geopolitical Balancing Act: Embracing the digital RMB must be balanced with Indonesia’s relationships with the West and its overall foreign policy. Indonesia is a member of the G20, an important U.S. security partner in the region (though not a formal treaty ally), and receives investment from many countries. If Indonesia were to be seen as moving too far into China’s monetary orbit, it could raise eyebrows in Washington or Tokyo. For example, if Indonesia announced it would conduct the majority of its trade with China in RMB and actively promote e-CNY, the U.S. might view it as acquiescing to China led financial architecture. This could have subtle repercussions, perhaps in how international aid or future partnerships are directed. Thus, Indonesia is likely to maintain a pragmatic middle path: cooperating with China on digital finance where beneficial, but also working with Japan, the U.S., and others on parallel initiatives. Indeed, Indonesia is part of the ASEAN Payments Connectivity project (with Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia) aiming to link real time payment systems in local currencies an effort that is independent of China. It also engages with the IMF on enhancing cross border payments, and with Japan on yen/rupiah settlement. By diversifying its monetary linkages, Indonesia hedges against over reliance on any single currency bloc. The comparison with Malaysia and Thailand is instructive: both have deep trade with China and are part of RMB use initiatives, yet they also retain strong ties to the dollar system and are developing their own digital currencies (Thailand’s Project Inthanon, Malaysia’s involvement in Project Dunbar with BIS). They aim for interoperability ensuring, for instance, that a Thai digital baht could exchange with e-CNY and with a future digital dollar seamlessly.

- Domestic Readiness and Infrastructure: Another practical dilemma is whether Indonesia’s financial infrastructure and regulations are ready to integrate with the digital RMB. Indonesia is still developing its digital payments scene (though it has made great strides domestically with systems like BI Fast and QRIS for QR payments). To interface with e-CNY, Indonesian banks and fintech firms need technical capability and compliance procedures for a foreign CBDC. There might be legal questions around taxation (e.g., if an Indonesian company is paid in e-CNY, how to record and tax that transaction) and around data (ensuring transaction data shared over the network does not violate privacy laws). Indonesia will likely take time to build capacity perhaps by first allowing limited pilots, maybe in special economic zones or among designated banks, before any wider use. Its peers have taken similar approaches: the UAE for example, has designated a handful of banks to participate in mBridge and to handle digital yuan clearing in Dubai, rather than open it floodgate to all banks. By comparing notes with such countries, Indonesia can learn best practices on safely integrating with the digital RMB ecosystem on a controlled basis.

In summary, Indonesia’s stance reflects a microcosm of the broader emerging market view: interest in the benefits of a pluralized currency system, yet caution to avoid new forms of dependency or instability. Indonesia is supportive of de-dollarization in principle (hence the LCS programs and task force) and is open to innovation like the digital RMB to the extent it furthers that goal without undercutting the rupiah. The country’s strategic importance also means it can serve as a bellwether if Indonesia successfully balances these factors, it could serve as a model for others in Asia and beyond. Countries like India (which similarly faces choices about joining global digital currency initiatives while safeguarding the rupee), or African nations involved in BRI, are surely watching these developments. Each will have its own calculus, but common themes emerge: engagement, caution, and the desire to extract maximum benefit from great power financial initiatives while retaining policy freedom.

Before concluding, we broaden back out to a global view: how can countries chart a strategic path in this emerging monetary order? The final section offers a framework for engagement and policy pathways that stakeholders from central bankers to institutional investors can use to navigate the promise and reality of the digital RMB and its counterparts.

Strategic Implications and Policy Pathways

The advent of the digital RMB and the push toward a more multipolar currency system carry profound strategic implications. Policymakers, central bankers, and financial leaders must craft responses that harness potential benefits while safeguarding national interests. Below, we outline a framework for strategic engagement with the digital RMB (and other CBDCs) and recommend policy pathways to maintain stability and sovereignty in a world of competing monetary blocs. This approach recognizes that completely resisting or wholly embracing the digital RMB are both suboptimal the optimal path lies in nuanced engagement, preparation, and diversification.

- Embrace Multilateral Collaboration on Digital Currency Standards:

Instead of viewing the digital RMB purely as a threat, countries (including the U.S. and allies) should engage China and others in setting common technical standards and governance norms for cross border digital currency use. This could occur through forums like the BIS Innovation Hub, G20, or IMF. By participating, countries can influence features like interoperability requirements, data privacy, and transparency. A collaborative approach might yield a global digital payments protocol that allows different CBDCs (e-CNY, digital euro, digital rupiah, etc.) to transact seamlessly. The IMF has even floated the idea of a multilateral platform for cross border payments that could host multiple CBDCs. Supporting such concepts can prevent the fragmentation of networks. It also reduces the risk that any one country’s system (be it China’s or the U.S.’s) becomes overly dominant or exclusionary. Practically, central banks should continue joining pilot projects (like mBridge) as observers or participants to stay at the cutting edge and ensure their interests are represented in design discussions. By co-creating standards, countries can neutralize geopolitical risk for instance, agreeing that no country will have unilateral kill switch authority on a shared network, or that oversight will be multinational. While big power rivalry can hinder cooperation, the broad consensus on the need to improve cross-border payments offers a diplomatic entry point. Even rival blocs have a stake in ensuring the global financial system remains interoperable. The presence of IMF and World Bank as observers in mBridge is a positive sign that bridges can be built.

- Develop Domestic CBDCs and Strengthen Local Currency Systems:

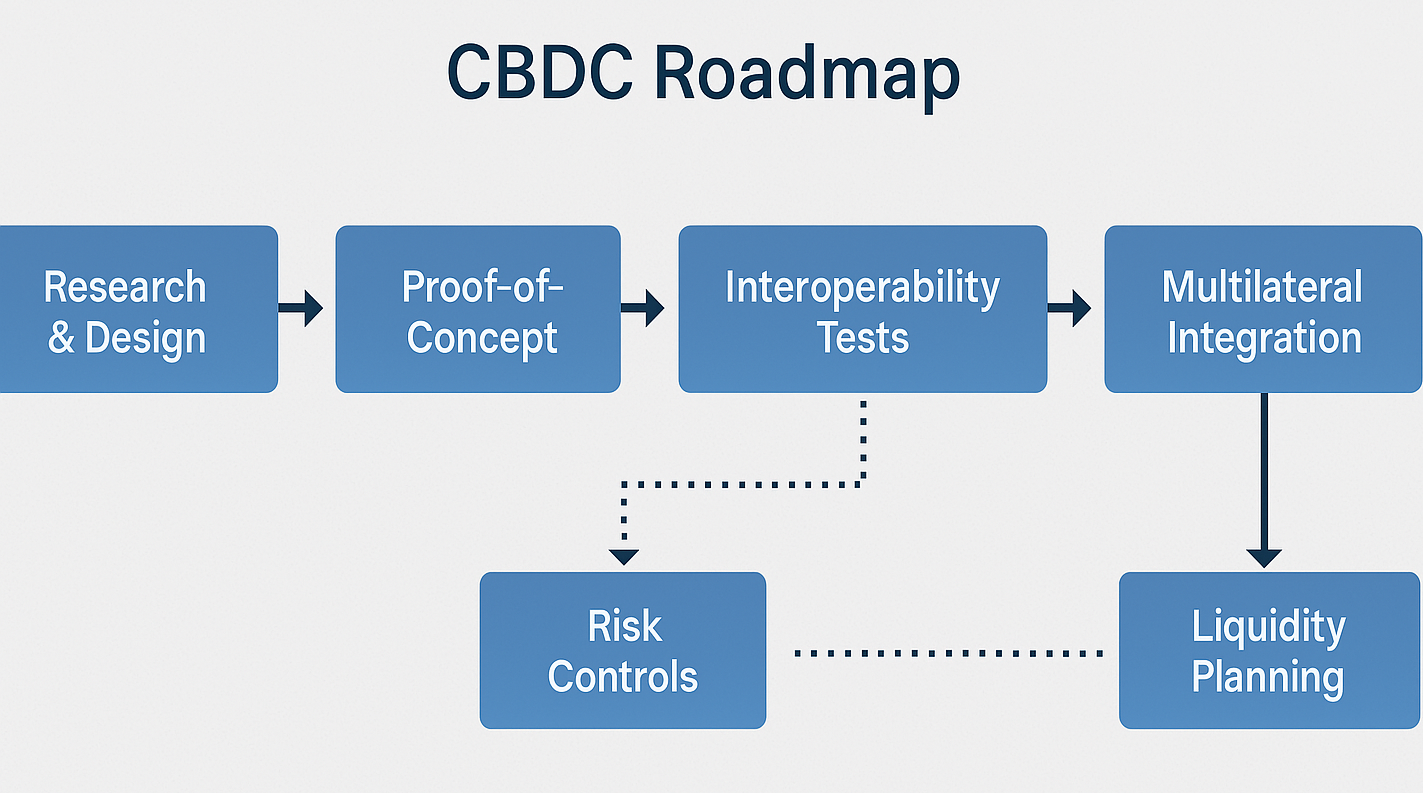

Step-by-step national CBDC roadmap from research to international interoperability, including regulatory checkpoints and risk controls

To maintain monetary sovereignty, it is imperative that countries modernize their own currencies for the digital age. A well designed domestic CBDC can improve payments efficiency at home and serve as the foundation for linking with others, so that foreign CBDCs (like the e-CNY) do not fill a void. Many emerging economies are moving this direction 66 countries are in advanced stages of CBDC exploration as of 2025. Whether retail or wholesale, a domestic CBDC gives the central bank better visibility and control over digital money flows, which is crucial if foreign digital currencies start entering the market. For example, if Indonesia launches a digital rupiah that is widely accessible, Indonesian consumers and firms would have less incentive to use e-CNY wallets for everyday transactions, preserving the dominance of rupiah domestically. Additionally, domestic digital currencies can be designed with safeguards (limits on holdings, etc.) to prevent destabilizing capital flight (something that might occur if people could convert en masse to a “strong” foreign CBDC during a local crisis). Central banks should prioritize interoperability features – ensuring their CBDC can interface with others. This might mean adopting international standards for messaging and data (ISO 20022 for payments, for instance) and possibly even open source technologies that facilitate cross ledger transactions. By having their own CBDCs and an interconnected regional network (for example, an ASEAN multilateral CBDC arrangement), countries create a first line of defense against both dollar and yuan domination. It’s akin to building a local highway system that can connect to either the Chinese “Belt and Road” or Western routes as needed, rather than relying solely on someone else’s road.

- Diversify Reserve Currencies and Hedging Strategies:

Monetary authorities and institutional investors should respond to this evolving landscape by diversifying their currency holdings, but in a prudent manner. For central banks, this means gradually increasing exposure to currencies like the RMB, euro, yen reflecting the reality that the dollar, while still paramount, may incrementally decline in share over time. A diversified reserve basket is a hedge against geopolitical risk (e.g., the risk of sanctions on one currency) and market volatility. However, diversification should be data driven: as long as RMB assets remain less liquid and freely usable, their weight should remain modest. The Fed’s analysis suggests the RMB will remain a niche reserve currency in the near term, so a move from say 2% to 5-10% allocation over several years could be a reasonable target for countries with high trade exposure to China. Alongside, maintaining substantial USD and EUR reserves is wise for stability. On the private sector side, institutions should explore RMB denominated instruments (bonds, etc.) as part of their portfolios, especially if yields and risks are attractive relative to Western markets. Already, some sovereign wealth funds and pension funds have upped RMB holdings following its inclusion in the IMF’s SDR basket. Risk management is key: use of forward contracts, swaps, or multilateral swap lines (like Chiang Mai Initiative in Asia) can help hedge currency mismatch. If an Indonesian bank takes on more RMB liabilities, it should match them with RMB assets or hedges to avoid open FX exposure. The development of an offshore RMB market (CNH) provides some hedging avenues, though still limited. Governments can encourage domestic financial institutions to build expertise in RMB trading and risk hedging so they are prepared if volumes increase. Liquidity arrangements like regional reserve pooling (e.g., the ASEAN+3 AMRO arrangement) could also consider accepting contributions in multiple currencies, including RMB, to be more flexible in crisis support. The guiding principle is not to put all eggs in one basket: the dollar’s dominance might gradually recede, but it will remain crucial; the RMB’s role will grow, but it is unlikely to take over completely. A balanced mix ensures resilience.

- Guardrails for Capital Flows and Financial Stability:

Policymakers should put in place regulatory guardrails to mitigate any destabilizing effects from foreign digital currencies. This includes updating foreign exchange laws to cover digital currencies explicitly for instance, clarifying that existing restrictions on foreign currency use apply equally to foreign CBDCs. In Indonesia’s case, BI might issue regulations on how e-CNY can be used: e.g., permitted for settlement of China related trade by authorized banks, but not for general public holding beyond a small limit. Clear rules will preempt confusion and arbitrage. Macroprudential measures may be needed if currency substitution accelerates such as liquidity requirements for banks on foreign CBDC holdings, or limits on local loans funded by foreign currency deposits. Central banks should also invest in monitoring infrastructure: the transparency of blockchain transactions can actually help here, as cross border flows in e-CNY (if accessible) could be tracked in real time by regulators (with cooperation from PBoC) to watch for sudden surges or patterns. In terms of capital account liberalization, countries should move cautiously. While using RMB for trade doesn’t necessitate opening up to unfettered capital movement, increased financial integration with China might bring pressure for more convertibility. Each country must assess its own comfort level and perhaps employ sandboxes: e.g., allow a certain volume of digital RMB to circulate in a controlled trial, study the effects on local liquidity and exchange rates, and adjust accordingly. If, say, dollar liquidity shrinks as a result, the central bank might have to intervene more in USD markets or arrange alternate lines. Coordination with China is also a tool – establishing swap lines in advance can assure a country that if it encourages RMB use and suddenly needs RMB liquidity (or vice versa), the PBoC would provide it. This kind of backstop arrangement, ideally reciprocal, can stabilize expectations and encourage usage under a safety net.

- Leverage Competition to Improve Existing Systems:

The rise of the digital RMB should spur the incumbents notably the U.S. and Europe to enhance the attractiveness of their own systems. For policymakers in those jurisdictions, this means supporting innovation like instant payment systems, lower cost remittances, and perhaps digital dollar/euro developments that address current shortcomings. The U.S. might not launch a retail CBDC soon, but it can empower private sector solutions (stablecoins regulation, FedNow instant payments, etc.) to ensure the dollar remains convenient and technologically up to date for global users. The competition can be healthy: if SWIFT and Western banks reduce transfer times from days to hours or minutes (through initiatives like SWIFT gpi or linking real time networks internationally), the relative advantage of the digital RMB diminishes. Similarly, improving financial inclusion in dollar dependent countries (via aid for fintech, for example) could lessen the appeal of switching to an alternative. Essentially, by treating the digital RMB as a wake up call, the West can address the grievances (high fees, slow speeds, sanction overreach) that partly drive de-dollarization. This in turn benefits all global users. For the countries in between, they should encourage this competition but avoid being forced into exclusive alignments. For example, ASEAN countries could concurrently connect to China’s CIPS and to Western payment hubs, ensuring multiple routes for transactions. If one system has issues, the other can be a fallback a redundancy that enhances resilience. In the long run, we may see convergence: if both Chinese and Western led networks become fast, cheap, and secure, the world benefits from a redundant but interoperable architecture (analogous to having both GPS and Beidou satellite systems for navigation two systems, but devices often integrate both to improve coverage).

- Strategic Diplomacy and Neutrality:

From a high level strategic view, many countries will find it in their interest not to explicitly choose sides in the shaping monetary order, but rather to maximize their strategic optionality. This means diplomatically supporting initiatives from all sides that align with their interests. A country like the UAE, for instance, is part of mBridge with China but also a close banking partner with the West it gains from being a node that connects different networks (Dubai aims to be a yuan clearing hub and a dollar hub). Indonesia and others can similarly play the role of a bridge. By engaging with China’s digital RMB on one hand and remaining active in IMF and U.S.-led discussions on the other, they increase their bargaining power. If tensions ever rise (e.g., sanctions or pressure to exclude one system), these countries can advocate for keeping financial channels open, citing their stake in both. In practical terms, this might involve legal arrangements such as maintaining both SWIFT membership and CIPS connectivity, or licensing banks from multiple countries to operate domestically, ensuring no single country can coerce them by withdrawal of services. Maintaining a stance of “active non-alignment” in the monetary domain cooperating with all, aligning with none exclusively – can help avoid entanglement in great power disputes. It’s a stance reminiscent of the Cold War Non Aligned Movement, updated for financial technology.

- Focus on Risk Education and Private Sector Adaptation:

Finally, governments and central banks should educate and prepare the private sector for these changes. Banks, fintechs, importers/exporters, and investors need to understand both the opportunities and risks of using digital RMB or other CBDCs. Training programs, guidelines, and perhaps incentives (or at least removal of disincentives) can encourage businesses to pilot using local currency or RMB for trade where beneficial. Conversely, firms should be made aware of the hedging tools they need if taking on RMB exposure. Regulators might require stress tests for banks that assume scenarios of much greater RMB usage to see how their balance sheets cope. This way, if policy shifts (like a big move to RMB settlement in certain sectors) happen, the financial system is not caught off guard.

By implementing these strategies, countries can navigate the new terrain deftly. The digital RMB does not have to be a disruptive threat; it can be an additional channel that, if managed well, complements existing ones. The world could move toward a more equilibrated currency distribution perhaps a future where, hypothetically, the dollar might be 40-50% of global reserves, the euro 15-20%, the RMB 10-15%, and others making up the rest, as opposed to the 1 currency dominance of the past. Such an outcome could enhance global stability if it avoids fragmentation. But reaching it requires foresight and coordination.

Navigating the Emerging Financial Order

The rise of China’s digital RMB is a landmark development in international finance one that encapsulates the shifting winds of geopolitics, technology, and economic power. While the promise of the e-CNY points toward a more efficient and multipolar financial system, the reality reminds us that entrenched structures and cautious actors change slowly. The emerging financial order will not be defined by a sudden overthrow of the dollar by the RMB, but rather by a gradual re-balancing and interweaving of currencies and systems. In this evolution, policymakers and financial leaders have a pivotal role to play in charting a course that maximizes collective benefit and minimizes risk.

China’s strategy with the digital RMB demonstrates visionary ambition marrying fintech innovation with long term geopolitical goals. It has already succeeded in sparking conversations worldwide about the future of money and prompted tangible actions (from multi CBDC experiments to new bilateral currency accords). The digital RMB has proven that alternatives to the status quo are possible, and in some cases, preferable for those at the margins of the current system. However, it has also laid bare the challenges of carving out a new pillar in the global monetary order. Trust, openness, and stability are not properties that can be engineered with code alone; they are earned through institutional track record and international cooperation. In these aspects, the dollar centric system for all its faults has deep roots. The digital RMB will need to coexist with that system for the foreseeable future, even as it seeks to gently reshape it.

For countries like Indonesia and its peers, the digital RMB’s rise is less about choosing one camp over another and more about adapting to complexity. They must be agile, learning to operate with multiple currencies and platforms, extracting advantages from each. The example of Indonesia shows that engagement with China’s currency initiatives can go hand in hand with reinforcing domestic monetary strength and regional collaboration. Those who manage this balance well will enhance their economic sovereignty in an era of flux turning a potential vulnerability (reliance on one superpower’s currency) into a position of leverage between giants.

From a global perspective, the most desirable end state is one of integration without domination. That means a world where digital dollars, digital euros, digital RMB, and others can all transact through interoperable networks under agreed norms competing and cooperating to drive down costs and expand inclusion, rather than erecting rival silos. Achieving this will require enlightened leadership and trust building among the great powers, alongside pressure from the rest of the world not to be forced into binary choices. In that sense, the digital RMB is also a catalyst for the U.S. and allies: it is prompting them to improve and perhaps reimagine aspects of the current system (from sanction policies to payment efficiency) in order to retain their appeal. The global monetary order a decade from now will likely be more plural, digitally interconnected, and regionalized than today’s, but if guided prudently, it need not be more fragmented or unstable.

In conclusion, the journey of the digital RMB underscores a central theme: finance is no longer just the realm of economics, but of strategy and technology. Nations must view their currency and payment systems as strategic assets. As the digital yuan blazes a trail, others will follow not just to compete, but to ensure they are not left behind. The promise vs. reality dichotomy will persist, with periodic hype about revolutions tempered by the inertia of legacy systems. Yet over time, incremental changes can amount to a transformation. Policymakers should prepare for that transformation now, shaping it through cooperation and foresight. The emerging financial order will be what we collectively make of it and with wise strategy, it can be one where innovation serves to enhance global prosperity and stability, rather than divide. The digital RMB is a powerful new tool in the toolkit; it is up to the international community to decide how to wield it in building the future of finance.

Reference:

- Brookings Institution – “The changing role of the US dollar” (2023)

- People’s Bank of China / BIS – Cross-border e-CNY pilot results (2022)

- IMF COFER data – RMB share of global reserves (2023)

- Federal Reserve – “Internationalization of the Renminbi: Progress and Outlook” (FEDS Notes, Aug 2024)

- SWIFT – RMB in global payments and trade finance (2023)

- Asian Development Bank – Dollar invoicing in Asia (2020)

- Bank Indonesia – Local Currency Settlement agreements (2021)

- ET Government (Economic Times India) – “China’s digital yuan reshaping global trade” (Mar 2025)

- Ledger Insights – “mBridge CBDC project observers” (Oct 2023)

- Atlantic Council – CBDC Tracker (Feb 2025)

- Carnegie Endowment – “Wholesale CBDC in Asia” (Feb 2023)

- Modern Diplomacy – “Indonesia’s Local Currency Settlement” (June 2024)

- The Diplomat – “Internationalization of RMB in Indonesia” (July 2020)

- The Banker – “Indonesia de-dollarisation task force” (Sept 2023)

- Federal Reserve – CIPS vs CHIPS volumes (2024), RMB swap lines analysis.